Top Ten Performances of 2019

Photo: Ken Howard

1. Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites. Metropolitan Opera.

As has become tradition in recent years, the Met closed its 2018–19 season with an unusual item that proved to be one of the season’s brightest spots. The final act last May was Dialogues des Carmélites, Francis Poulenc’s wrenching depiction of the sixteen Carmelite nuns who went to the guillotine just weeks before the end of the Terror in 1794. With Isabel Leonard and Karita Mattila headlining a superb cast, and with Yannick Nézet-Séguin crafting a limpid account of Poulenc’s rich but astringent score, this was an emotionally devastating performance. Let’s hope this twentieth-century masterwork gets more than a three-show run next time it comes around. (ES)

Photo: Caitlin Ochs

2. Mahler’s Symphony No. 6. New York Philharmonic/Simone Young.

Before the first notes sounded, this was already the stuff of classical music drama: conductor Simone Young was filling in at the last minute for Jaap van Zweden, who was injured. Then from the those first notes, one was overwhelmed by musical drama and narrative. With absolute formal and structural clarity, phrasing and tempos that were perfect, and a near-vicious intensity of playing from the Philharmonic musicians, this was Mahler with the inevitability that always resides in the music but that is too rarely heard. (GG)

Photo: Jennifer Taylor

3. Music of Béla Bartók. Budapest Festival Orchestra/Iván Fischer.

In a Béla Bartók April weekend to remember with Iván Fischer as emcee in Carnegie Hall, fine performances of down-home “roots” music—a children’s choir on Saturday night, a string band Sunday afternoon—established the Hungarian language and melos in listeners’ ears. Then Fischer led his supple-toned, old-school ensemble, the Budapest Festival Orchestra, in richly idiomatic performances, on successive nights, of the Concerto for Orchestra and Duke Bluebeard’s Castle. (DW)

Photo: Marty Sohl

4. Donizetti’s La Fille du Régiment. Metropolitan Opera.

La Fille du Régiment, Donizetti’s sunny romp through the Tyrolean hills, may feel like a light piece, a silly romantic comedy with a few memorable numbers. In a revival this February, the enchanting production by Laurent Pelly and a starry cast made this goofy opéra comique seem full of deep meaning. Javier Camarena’s Tonio was one for the ages and he was called on to encore “Pour mon âme” every night, while Pretty Yende’s coloratura fireworks and keen musical instincts in the role of Marie made for the greatest triumph yet in a young but already impressive career. From bottom to top, this cast boasted irresistibly playful performances that proved romantic comedy can be as profoundly joyful as the most heart-rending drama can be tragic. (ES)

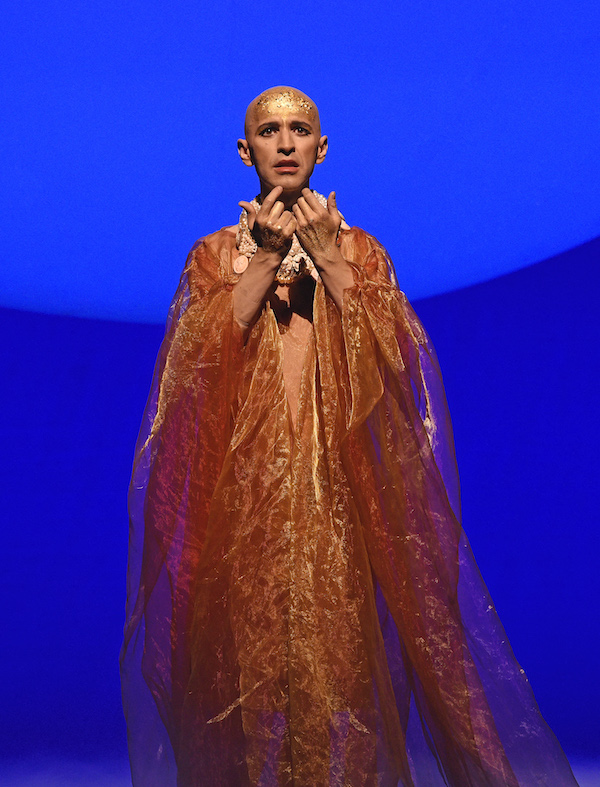

5. Glass’s Akhnaten. Metropolitan Opera.

One of the finest opera productions this writer has ever experienced, this was also the finest thing one has seen at the Metropolitan Opera in years. Phelim McDermott’s staging and Anthony Roth Costanzo’s powerful vocal and physical presence delivered the last degree of expression and meaning in this opera. In doing so, they showed how Akhnaten, with its drama entirely encapsulated in the music, is one of the grandest works in the repertoire. (GG)

Photo: Tristan Cook

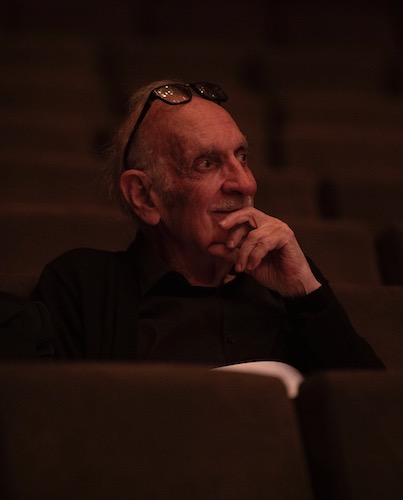

6. George Crumb’s 90th Birthday Celebration. Program I. Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.

In another pair of April programs, the sage of Media, Pennsylvania presented the world premiere of a new Crumb adventure, KRONOS-KRYPTOS—four movements of intricate percussion wizardry. The composer was also honored with loving, imaginative performances of his avant-garde classics (Black Angels, Music for a Summer Evening, Vox Balaenae), and rare items (Four Nocturnes for violin and piano; Four Early Songs and American Songbook III). (DW)

7. Schubert’s Winterreise. Joyce DiDonato and Yannick Nézet-Séguin.

Winterreise is not a piece that gets easily worn out: it is so rich in ideas and emotions that a new interpretation by a great artist will reveal something new about the piece, almost without fail. Joyce DiDonato, who first sang the iconic cycle just a year earlier, brought an interpretation to Carnegie Hall that felt strikingly raw, all the more fresh because frequent repetition hadn’t yet taken the edge off her instinctive, emotional response to the work. Though he does not frequently perform as a pianist these days, Nézet-Séguin gave an earnest rendition of the accompaniment that cut right to its basic truth. (ES)

Photo: Tristan Cook

8. George Crumb’s 90th Birthday Celebration. Program II. Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.

For the second of the two concerts in this series, CMS performed Crumb’s most famous work, Black Angels, and his most beautiful of many beautiful pieces, Music for a Summer Evening (Makrokosmos III). These were stunning performances—beyond playing, the musicians put themselves into Crumb’s world of colors, textures, light and darkness, and brought out the instinctive rituals at the heart of the music. (GG)

9. Les Arts Florissants at the Cloisters.

Four centuries after his death, the music of Carlo Gesualdo, Prince of Venosa, hasn’t lost its power to shock and amaze, as evidenced by the vibrant yet profoundly spiritual performance of his sacred madrigals by Les Arts Florissants October at the Cloisters in October. Six unaccompanied singers were all it took to fill the museum’s Fuentidueña Chapel with sounds ranging from gleaming major triad chords to a tumultuous hubbub of dissonance. The nine Responsories for Maundy Thursday, published in 1611, memorialized the events leading up to the crucifixion of Jesus in stunningly modern-sounding music. (DW)

10. Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7. Philharmonia/Esa-Pekka Salonen.

This was a beautiful, sensitive performance from the Philharmonia, and beyond that the sense of pacing and time were Brucknerian in the most meaningful way. The music unfolded simply and naturally, flowing like the many stages of a deep and eternal river, alternately peaceful, wrenching, and finally at rest. (GG)

Honorable Mentions

Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra provided an early-season highlight with their Carnegie Hall concert in October. The evening opened with a stirring rendition of Valerie Coleman’s Umoja, and Hélène Grimaud gave a blistering performance of Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 3. But the standout item of the night was an unforgettable performance of Richard Strauss’s An Alpine Symphony, in which the orchestra’s vivid playing evoked nature’s terrifying power just as easily as its bucolic bliss. (ES)

Remember Paul Hindemith? The German-born, naturalized American expressionist-neoclassicist composer seemed to be charting a middle way in the tonal-atonal wars of the mid-20th century, but after his death in 1963 musical fashions turned in other directions, and his works were heard less often. Conductor Salonen brought him back in style in these November concerts, coupling his jazz-age Bach pastiche Ragtime (Well-Tempered) with a vital performance of his Nazi-era tribute to artistic freedom, the Mathis der Maler Symphony. Salonen added, for good measure, the local premiere of his own colorful Gemini for large orchestra. (DW)

Philippe Jordan and Julia Fisher with the New York Philharmonic. The contents of this program, Prokofiev’s Symphony No. 1, the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7, were common enough to keep this out of the Top Ten for 2019. But the execution, Fisher’s deep and detailed thinking about the concerto, and Jordan’s wisdom about the best musical choices in the symphonies, were all exceptional. To that add the verve of the Philharmonic’s playing, and the standard fare became a hearty gourmet feast. (GG)

Alisa Weilerstein lit up a New York Philharmonic program with her gripping performance of Saint-Saëns’s Cello Concerto No. 1. Franz Welser-Möst and the Cleveland Orchestra opened Carnegie Hall’s season with a rapturous concert suite from Der Rosenkavalier. Down in Zankel Hall, Ian Bostridge and Brad Mehldau gave a memorable recital that featured a sublime Dichterliebe alongside Mehldau’s own ingenious cycle, The Folly of Desire. A sensational cast featuring Nadine Sierra, Luca Pisaroni, Adam Plachetka, and Susanna Phillips, highlighted a glowing, riotously funny Nozze di Figaro at the Met, conducted brilliantly by Antonello Manacorda in his debut. And the timeless duo of Anne-Sophie Mutter and Lambert Orkis gave a splendid recital at Carnegie Hall that featured a sublime rendition of Debussy’s Sonata for Violin and Piano. (ES)

Most disruptive early-music concert

Musicologists were reaching for their smelling salts as Baroque flutist Emi Ferguson and the period-instrument group RUCKUS played a mash-up of a Bach flute sonata with the “Goldberg” Variations, threw in syncopated counterpoints of their own devising, rewrote the master’s figured basses, and got a banjo involved in there somewhere, all because it sounded good to them. This November mostly-all-Bach concert on the venerable Music Before 1800 series also sounded good to the subscribers, who stood and cheered. (DW)

Pinch Hitter of the Year

This award usually goes to a young cover singer, waiting for that chance-of-a-lifetime moment to save the day with a breakout performance. At 65, Gregory Kunde has to be among the oldest tenors ever to step in as a mid-show replacement. With Aleksandrs Antonenko struggling to get through the first act of the Met’s Samson et Dalila, Kunde came on in relief after intermission and gave a heroic performance, showing a full caramel color and focused tone that many tenors three decades younger would envy. (ES)

The It’s-About-Time Award for Opera

Not soprano Anna Netrebko in Adriana Lecouvreur at the Met—that New Year’s Eve treat was technically in 2018. No, think instead of courage, heroism, civil rights and drag queens, then ask: How did we go fifty years without an opera about the Stonewall Inn? As written (at last) by composer Iain Bell and librettist Mark Campbell and produced by the New York City Opera last June at Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Rose Theater, Stonewall bypassed gay leaders and politicians to tell affecting stories of the ordinary LGBTQ folks who went to a bar to dance and have a little fun, and ended up making history. (DW)

Put it on the shelf

With a final run this past spring, the Met finally retired the Sonja Frisell production of Verdi’s Aida. Since its debut in 1988, this Aida has been a fixture of the met’s repertory, its massive sets offering the grandest expression of grand opera. While the sets had a tendency to wobble in their old age, the sheer spectacle of this staging made it an audience favorite for decades. Director Michael Mayer will have quite the challenge replacing it when he helms a new rendition to open the company’s 2020–21 season. (ES)

Minimalists? The New York Philharmonic?

Composing for the musical establishment they once defied, octogenarian composers Philip Glass and Steve Reich showed undiminished powers and questing imaginations in new works conducted by Jaap van Zweden at concerts in September and December respectively. Minimalist Glass maxed out on turbulence and discontinuity depicting a mad monarch in the world premiere of his King Lear Overture, to stunning effect. Reich’s more modest goal of composing a concerto grosso featuring his usual small ensemble in Music for Ensemble and Orchestra achieved more modest results in its New York premiere, thanks to less-then-crisp execution. (DW)

Founding Father Remembered

Last spring, a largely but not entirely African-American assembly of singers, instrumentalists and speakers crammed the auditorium stage of the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center to celebrate the legacy of the singer, composer, arranger and music editor Harry T. Burleigh, the grandson of slaves who, as a pupil of Antonín Dvořák in New York in the 1890s, is credited with introducing the Czech master to America’s “Negro” idiom. And thereby hung a tale not just of the Largo from Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony, but of high-quality classical works by African-Americans Burleigh, William Levi Dawson, Florence Price, and William Grant Still, all performed that May night with gusto and professional polish. (DW)

Suburban Surprise

The Montclair Orchestra, in the affluent New Jersey suburb of the same name, is a “developmental” ensemble, with the worthy goal of assisting music education by mixing promising students with seasoned pros in its ranks. Led by David Chan, whose day job is concertmaster of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, it gives half a dozen well-attended and well-received concerts a season. But maybe it took a jaded New York critic, at a concert in March, to sit up and realize that Chan had just led his band in a performance of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor that, for crisp execution, fleet pacing, and dark expressivity, would best most or all of this country’s major orchestras. (DW)