CMS celebrates George Crumb, from early works to a world premiere

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center gave the world premiere of George Crumb’s “KRONOS-KRYPTOS” Sunday at Alice Tully Hall. Photo: Tristan Cook

As of Sunday’s world premiere of his new percussion quintet, it’s clear that composer George Crumb, nearing his 90th birthday in October, can still transport you to the mysterious realms of Crumbworld, and once there, surprise you.

In the first of two concerts honoring this one-of-a-kind American master, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center unveiled KRONOS-KRYPTOS–composed last year with a commission from CMS and the Library of Congress–at the end of a program that spanned the 70-plus years between Crumb’s earliest published composition and his most recent.

While only one of the five other Crumb works in the nearly three-hour-long concert could be called iconic—the 1971 piece Vox Balaenae for Three Masked Players (i.e., flute, cello and piano)—all revealed a composer marching to a different drummer than the rest of his generation, or any generation.

Any question whether he still hears that beat was immediately dispelled by the intricate percussion wizardry of KRONOS-KRYPTOS, said by CMS to be the first commission Crumb has accepted in 15 years. (He has composed plenty in that time, but all on his own initiative.)

The percussion fivesome of Daniel Druckman, Ayano Kataoka, Ian David Rosenbaum, Eduardo Leandro, and Victor Caccese realized Crumb’s vaporous atmospheres and dazzling lightning strikes with pinpoint coordination and a singular vision.

Crumb’s first surprise was structuring the new piece in a familiar, Mahlerian four-movement plan: exuberant opening, mournful adagio, wild scherzo, meditative finale. Appropriately for a mid-April premiere, the work began with “Easter Dawning,” a joyous peal of metal percussion that was, in fact, originally composed for carillon in 1992. The addition of other instruments such as bass drum, bowed flexatone, and xylophone lifted the music out of the bell tower and into imaginary spaces.

“A Ghostly Barcarolle” swayed gently as soft-edged tones stole in and out, pianissimo. A vibraphone set on its longest vibrato put a spooky throb under all. Now and then, water was poured from a clear pitcher into a clear bucket, a subtle sound with a striking visual effect.

One shouldn’t have been surprised that something completely different was coming in a movement titled “Drummers of the Apocalypse.” Still, nothing in this concert full of delicate nuances at the edge of perception prepared one for this thunderous, inexorable assault of unpitched percussion, punctuated by barbaric shouts. It was not heard to imagine the “end of days” sounding exactly like this.

Then what? Nothing but echoes—specifically “Appalachian Echoes,” quiet, fragmentary music that hinted at the folk melodies and stargazing nights of the composer’s boyhood in Charleston, West Virginia. Near the end, player Druckman tapped out the song “Poor Wayfaring Stranger,” already heard earlier in the concert, on a Caribbean steel pan. The movement emerged from silence and later vanished back into silence, beginning and ending with players Leandro and Kataoka noiselessly beating the air with their sticks.

The response of the audience was anything but noiseless, as waves of appreciation and birthday well-wishes rose from the auditorium to the composer in his balcony box overlooking the stage.

The new piece’s literally cryptic title, referring to “time” and “secret code,” seemed to apply not only to that individual work—with its mysterious, time-inflecting events of resurrection and apocalypse—but to Sunday’s program as a whole, a journey from the composer’s teen years to seasoned age that hopped around in time.

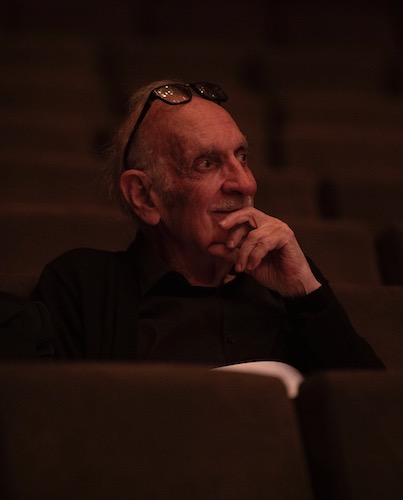

George Crumb. Photo: Tristan Cook

The concert opened with Three Early Songs of 1947, rare survivors from Crumb’s student days, which showed the composer already going his own way without obvious models. Gently intoning melancholy texts by Robert Southey and Sara Teasdale to a glinting piano accompaniment, soprano Tony Arnold and pianist Gilbert Kalish kept it simple, so that the occasional crescendo became a dramatic event.

For Crumb as for Bartók, night is not a quiet time. In a vivid performance by violinist Kristin Lee and pianist Gloria Chien of his 1964 piece, Four Nocturnes (Night Music II), the dark hours were full of insect calls (violin harmonics and glissandos across piano strings) and things that go bump (knocks and taps on instrument bodies). The audience could visually admire Chien’s skilled playing inside the piano, reflected in the instrument’s shiny lid.

American Songbook III: Unto the Hills was part of a decade-long project during the 2000s to give folk songs settings that suggested their “psychological depth and mysticism,” as the composer put it. Soprano Arnold sang the nearly unaltered melodies with subtle inflection that didn’t call attention to itself, while the percussion-and-piano group of Druckman, Rosenbaum, Kataoka, Leandro and Kalish (with Kataoka occasionally playing inside the piano with her sticks) evoked the songs’ yearning, sadness, and occasional humor. An instrumental interlude, “Appalachian Epiphany: A Psalm for Sunset and Dusk,” evoked the onset of night in gentle tintinnabulations.

Through performances and recordings, pianist Kalish was instrumental in Crumb’s rise to fame in the 1970s, and on Sunday he performed “Processional,” a piano solo Crumb composed for him in 1983. Playing solely with fingers on keys (no thumping the instrument or reaching inside it), Kalish “processed” at varying tempos with plenty of rubato, amid clouds of Debussyian piano colors and the occasional startling metallic clang.

Playing in blue lighting and wearing half-face masks as the composer specified (to “dehumanize” the performance, he said), flutist Tara Helen O’Connor, cellist Mihai Marica, and pianist Chien evoked songs of the humpback whale and the vastness of geological time before the existence of humans in Vox Balaenae.

As executed by these imaginative players, the work’s celebrated “special techniques”—the flutist’s simultaneously playing and singing into her instrument, the cellist’s eerie harmonic glissandos, the pianist’s stroking the strings with a chisel—blended into a vision of an unknowably ancient, strangely sentient whale-world.

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center performs Crumb’s Black Angels and other works in “George Crumb at 90—Part II” 7:30 p.m. Tuesday at Alice Tully Hall. chambermusicsociety.org; (212) 875-5788.