Huang Ruo’s “Paradise, Interrupted” proves compelling at Lincoln Center

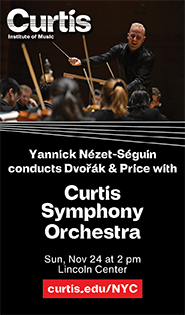

Yi Li and Qian Yi in Huang Ruo’s “Paradise Interrupted” at the Lincoln Center Festival. Photo: Stephanie Berger

One of the distinguishing features of the Lincoln Center Festival is its eagerness for variety. In contrast to its near neighbor, the Mostly Mozart Festival, which presents a robust collection of Western Classical music, the LCF takes pride in offering items from an array of art forms and cultural traditions.

There is little in the way of traditional European-style opera at the Festival this year (the conventional taste this year is largely sated by The Merchant of Venice from Shakespeare’s Globe), but Paradise Interrupted, which had its New York premiere Wednesday night at the Gerald W. Lynch Theater, is an intriguing, often bewildering piece.

Paradise Interrupted in a way marks a return to one of the festival’s traditions, having presented multiple Chinese musical dramas over the past two decades. Inspired primarily by the Chinese kunqu tradition, the eighty-minute piece combines movement, theater, poetry, and music.

The basic idea strongly resembles what we think of as opera in the West, a dramatic and musical fusion—and yet part of what makes Paradise Interrupted so compelling is the ways in which it surprises. The text is dreamily poetic, veiling the narrative in a thick fog of symbolism, and the lead singer’s movements consist largely of highly stylized, specifically choreographed, unfamiliar gestures.

As the Miltonian title indicates, Paradise Interrupted takes significant cues from the biblical story of the Fall, showing a woman whose bliss is threatened when the idyllic sheen on her surroundings is suddenly lifted. The combination of this story with that of The Peony Pavilion (a kunqu drama that appeared at the Lincoln Center Festival in 1999) creates a dreamlike psychological drama that is often inscrutable.

Yet the piece is powerfully communicative thanks to its superb realization, beginning with the score. Huang Ruo’s writing, incorporating both Western and Chinese instruments, is generally light, often providing a bare accompaniment to the singers, but it lands with dramatic force, powered by the depth of its imagination.

Jennifer Wen Ma’s staging has a similar spareness—its palette consists entirely of whites, blacks, and grays, elegantly mixed to produce a tableau more striking than many more colorful production designs. Atmospheric videos across the back wall complement the beautiful, inventive naturalistic shapes that seem to grow around the stage as the opera progresses. A black paper forest looms ever larger at the periphery, choking the air around a single tree that sprouts leaves and fruit, lowered from the fly space.

Leading the cast as the Woman, Qian Yi, who headlined LCF’s previous kunqu productions, was compelling, if hard to decipher. She is the only member of the cast whose career rests primarily on performance of kunqu opera, and her gestures, presence, and characterization were mesmerizing, even if her voice did not have the lush, luminous quality we are accustomed to in Western opera houses. Her presentation felt remote, almost opaque, but in a way that betrayed a complex bubbling of emotions underneath her composed exterior.

Equally impressive in a more familiar vocal style were the excellent supporting cast, who filled various roles, including the Elements and the Four Directions. John Holiday’s chilling countertenor made him an imposing presence; Yi Li’s tenor was smooth and ringing as the Lover. Baritone Joo Won Kong and bass-baritone Ao Li sang with rich, growling tones, and the musicians of Ensemble FIRE, led by Wen-Pin Chien, provided vivid, assured accompaniment.

Paradise Interrupted will be repeated 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday at the Gerald W. Lynch Theater at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. lincolncenterfestival.org