Slow to get under sail, “Moby-Dick” builds to powerful impact in Met debut

The very concept seems impossible: taking Herman Melville’s novel Moby-Dick—not just one of the greatest works in American literature but also one of the most unconventional—and turn it into an opera. The book is more than just the story of crazed and obsessive Captain Ahab’s hunt for the whale Moby Dick, which had previously bitten off his leg; there is poetry, theater directions, catalogues, and other devices. It is much more than a story, much more than a novel.

But composer Jake Heggie and librettist Gene Scheer created an adaption that debuted in 2010 at the Dallas Opera, and now their work has made its way to the Metropolitan Opera, opening Monday night in Leonard Foglia’s impressive production.

There is a high-powered cast in this staging, with tenor Brandon Jovanovich as Ahab, tenor Stephan Costello as Greenhorn (a.k.a. Ishmael), bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green as Queequeg, and soprano Janai Brugger as cabin boy Pip. The great baritone Peter Mattei was scheduled as Starbuck, but withdrew from the opening performance due to illness; he was replaced by young baritone Thomas Glass, who has previously appeared on the Met Stage as Yamadori in the 2022 run of Madama Butterfly. With Karen Kamensek in the pit, Moby-Dick was touch and go for a considerable time, but ultimately delivered some real beauty and power.

Scheer’s libretto reduces the novel down to the central plot of Ahab chasing the whale, reminiscent of John Huston’s 1956 film but with different emphases. It opens with the ship already at sea and compresses one year’s worth of time into its scenes. The opera is the chase, the tragedies that ensue, and the resolution.

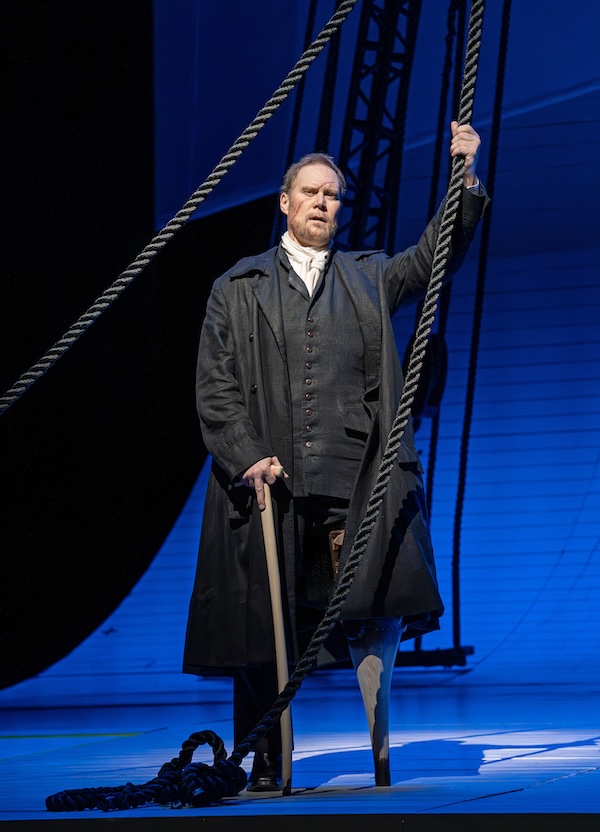

Ahab is more than just the central character, his singing literally directs the events. Jovanovich, limping around on an artificial peg-leg, was commanding. He pushed his sturdy tenor to the edge to show Ahab as crazed and domineering, and could also seduce the crew with a glimpse of humanity. He was, vocally, the core of the performance and had the most fire and range all evening.

One part of that range was an Act II duet with Starbuck, some of the loveliest music of the evening and the key point before the climax. The two characters sing about home on Nantucket, Starbuck trying to convince Ahab to turn back. The gentleness in Jovanovich’s sound and phrasing expanded the characterization, and was a fine blend with Glass’s warm baritone.

Glass was exceptional. It wasn’t just playing the role of the conscience of the opera in Moby-Dick, of all stories, but filling in for Mattei, who is one of the greatest of contemporary opera performers. While the latter can sing with a lot of freedom, Glass seemed to stick directly to the part, and his smooth, graceful sound and musical phrasing were expressive and affecting. His Act I aria, contemplating mutiny and murder, was the finest vocal moment of the night. His beautiful singing showed a real understanding of the drama and forced life into what up to that moment had been a thin experience. In Act II, he was equal to the increasingly strident and intense Ahab, a substantial feeling of peace against the Captain’s war.

Act I was lukewarm, and a lot of that had to do with the singing and orchestral playing. Queequeg and Greenhorn are the first characters to sing, and Green and Costello were subdued in the opening scene, both their voices uncharacteristically thin and without much weight in their projection. The orchestra’s playing was precise and delicate but also felt a little underpowered. Jovanovich’s first appearance ramped up the overall energy, Brugger was stellar from her first moment, her voice ringing out with charm, and they, inadvertently, revealed structural problems with Heggie’s score.

There is a conceptual conflict inside Moby-Dick: Melville’s novel is more experimental than most of 20th century literature, Heggie is a tonal, tuneful, conventional composer in the extended 19th century style. The music is transparent and never heavy and favors consonant harmonies, even as there is the Wagnerian device of a couple of themes that run through the work, accumulating musical meaning through changing contexts. The opera forces an unruly source into a linear form. That’s not good or bad, it’s the nature of turning literature into music drama.

But it makes for a lopsided structure. The long first act has to build the opera’s world and introduce many characters and give them a chance to sing, including tenor William Burden as Flask and baritone Malcolm MacKenzie as Stubb, both lively. There’s so much scene-setting that there’s no discernible culminating point to the opera—even as the libretto hints at fate, there’s no hint of fate in the music. It’s not until the last couple of scenes before the drama builds not just weight but a sense of forward movement directed toward a specific point.

Once that appears, though, the opera is tremendous. Act II starts with a slow burning fire, the music is much richer and has a sense of inevitability, and even calmer moments, like the encounter with the ship Rachel with Captain Gardiner (baritone Brian Major, singing with force and feeling from the darkness of one of the box seats), are full of tension. Green and Costello were in full voice, the orchestra had a new level of energy. The climax was like the slow eruption of a volcano, music and physical action coming together with a real feeling of tragedy. The performances brought this out, but it’s Heggie’s music that drove them.

Credit also this fine staging by Foglia, in his house debut. The opera takes places shipboard, so there are masts and rigging, and also intelligent digital projection on the curtain of stars, constellations, and the Pequod itself, all white lines on the black surface. There is also a curved wall at the back of the stage that is put to clever use as not only part of the hull of the ship, but becomes the ocean when the crew sets out in the boats to hunt the whale—many of them knocked into and under the waves, to slide away and disappear. One literally sees men lost to madness, and it’s an unforgettable moment.

Moby-Dick runs through March 29. metopera.org