String Orchestra of Brooklyn brings understanding to music of Arvo Pärt

There is a difference between playing music and making music—between producing all the notes on the page and getting to the point and purpose of why the notes were written.

At St. Ann and the Holy Trinity Church in Brooklyn Heights Saturday night, the String Orchestra of Brooklyn showed what it all boils down to with a marvelous example of not just making music, but a live gathering together of musicians and audience.

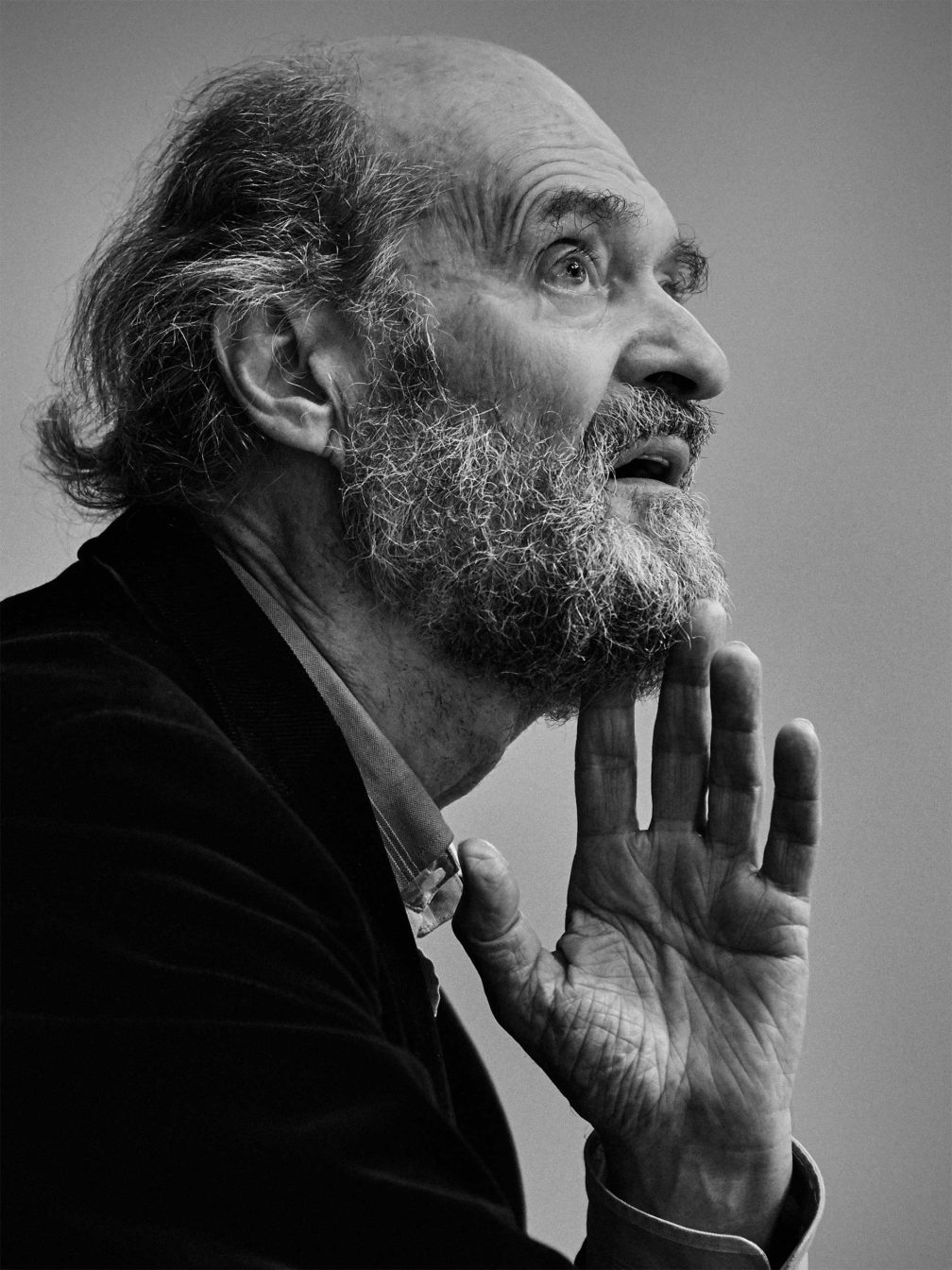

Arvo Pärt turns 90 this year (his birthday is September 11), and the program honored this milestone. With Eli Spindel conducting, SOB played Pärt’s Symphony No. 3 on the first half, then added violinist Michael Jorgensen for Fratres in the version for string orchestra and percussion, soprano Sarah Moulton Faux for L’ábbé Agathon, and finished with the Cantus in Memory of Benjamin Britten.

The performances were not always technically precise but they were musically powerful, with the feeling that musicians and audience were hearing the same expressive depths and force in the pieces.

And there was a larger historical and social context that seemed to surround the experience and that added rich dimensions. Spindel himself was taking tickets before the concert, and the sound of the church’s radiator hissing and snapping gave it a neighborhood feeling. Even with an incoming storm, there was a substantial crowd. The stark gothic interior of the church was not just acoustically fine but the place from which Part’s aesthetic developed.

For the symphony, SOB was augmented with full woodwind and brass sections. This was an evocative way to establish the concert and place Pärt within his own story, rather than the fully formed composer who hit the West via the classic 1984 ECM album Tabula Rasa.

Written in 1971, the Symphony No. 3 is an important transitional work from in between his break from what was politically acceptable in the Soviet Union to his modernist rewriting of liturgical musical ideas from the Medieval and early Renaissance. Pärt, like his peer Alfred Schnittke, who played the prepared piano on Tabula Rasa, discovered a past forbidden by authoritarian ideology, and used it but to advance present music and his own aesthetic freedom.

The Third Symphony has a foundation is plainchant style phrases, but is put together in a constructivist manner that’s not dissimilar from Bruckner. It has Pärt’s materials but not yet the organic, large-scale form that would soon develop in masterpieces like Fratres. But each block of sound and events is stirring and strives to connect an internal contemplative experience to the outer world. Even with occasional messy entrances and some intonation problems in the strings and horns, the musicians brought a sense of emotional fullness to the piece.

The second half was superb. Along with the orchestra Jorgensen himself had a few intonation issues at the start of Fratres, but the soloist and Spindel just kept laying out the phrases with a steady, implacable pace that accumulated expressive weight with each new stretch. Technique grew more refined as the playing went, until at the end Jorgensen’s long, final stretch of singing harmonics was as slicing and shining as a diamond filament.

Moulton Faux’s voice was just as shining in Pärt’s setting of a 4th century Egyptian parable of the Abbot meeting and aiding a leper he meets on the road to the market. Her pure intonation and excellent articulation served the exactitude of Pärt’s writing, a careful display of the story, the narrative and thematic transformation of the simple and ordinary into the spiritual. Yet coming between two instrumental works, Agathon had a paradoxical secular quality to it, as if the literalism of the words collapsed the sense of exalted mystery in the Fratres and Cantus.

Cantus was the finest performance of the night, expert and flowing in every way. The piece is a simple series of descending scales that reach their end, then start again, the dynamics rising as each one passes until reaching triple forte at the end. But Spindel held back the volume. The playing was gentle but inexorable, like the snow that was falling outside, whitening and silencing the surrounding streets, each moment adding weight and layers, a massive amount of feeling rather than just sound.