Kutasi’s Amneris provides the highlights in Met’s uneven, archaeological “Aida”

As the fedora-hatted archaeologist was lowered into the Egyptian temple to begin the Metropolitan Opera’s performance of Verdi’s Aida Tuesday night, he took a tumble while disengaging from his rope.

That was only the first misstep in a new production that already had the misfortune to follow a legend, and then came up with few reasons to do so.

For 36 years, Sonja Frisell’s mounting of Aida at the Metropolitan Opera, with its monumental Pharaonic sets by Gianni Quaranta and brigades of supernumeraries, had been a major local attraction, embodying “New York spectacular” as surely as the Chrysler Building or the Rockettes.

As the decades went on, the question arose whether this version of Aida had become a timeless classic or had overstayed its welcome. Plans for a change were laid as early as 2019, but a pandemic intervened. The new production by Michael Mayer just made it under the wire to open in the waning minutes of 2024.

Of course, New Year’s Eve symbolizes new beginnings, and the gowned and tuxedoed onlookers were primed for the latest 21st-century take on the old masterpiece. What they got was a conventional staging with boxy (if profusely decorated) sets and a handful of novelties such as that framing device involving archaeologists.

What exactly the archaeologists were doing there wasn’t clear. They would appear, beaming their flashlights around, at the beginning of a scene, then melt away as the opera’s action began. During one scene change, an archaeologist sat with her sketch pad stage left, drawing an ancient Egyptian bas-relief, her pencil strokes projected line by line on the scrim that filled the Met proscenium. Then the scrim rose to reveal that sculpture in the flesh, so to speak.

That was a nice trick (courtesy of the projection design studio 59), but these interlopers’ big moment came when, instead of people and animals marching across the stage to Verdi’s Triumphal March, archaeologists marched out of the temple carrying statues and other artifacts. Apparently they were included in this production to reflect the West’s artifactual rapaciousness as well as the European Egyptomania that gave rise to this opera in the first place. In any case, they added nothing to Verdi’s work, and thankfully had vanished by the later acts.

There were times, especially in that later action, when one wondered if the title of the opera shouldn’t be Amneris instead of Aida. Imperious, furiously conflicted, besotted with love for Radamès, even a half-decent Amneris can steal the show from the titular heroine, and Judit Kutasi was all that and more Tuesday night. Strong enough in the low range and with a trumpet on top, the Romanian mezzo-soprano dominated every scene she was in, whether her character was winning or losing. (The opera’s shift in dramatic focus was emphasized by placing the evening’s single intermission between Acts II and III.)

Kutasi had all too vulnerable a target in Angel Blue, in her Met role debut as Aida. The dynamic between princess and princess-as-slave is hard enough to navigate dramatically without a mismatch of voices, and Blue, justly admired for the warmth and lyricism of her Bess and multiple roles in Fire Shut Up in My Bones, never found the regal presence that makes Aida’s demise so affecting. But when needed, she could summon both vocal power and floating high pianissimo, and she delivered her big soliloquies “Ritorna vincitor!” and “O patria mia” confidently and without affectation.

It’s also possible that Blue had to trim her sails vocally in scenes with Piotr Beczała as Radamès, who was not in his best voice Tuesday owing to a cold, it was announced after intermission. The Polish tenor’s tone still sounded round and well-supported, and he navigated his entire range including the high notes, if without his usual ringing tone. One missed that wail of despair amid the revelry of Act II, as Radamès’s world was falling apart at the moment of his greatest triumph, but at other times Beczała’s acting skills, though modest, carried him through.

The job of the King in this opera is to look imposing and get his lines out, and bass Morris Robinson delivered handsomely on both. The high priest Ramfis, on the other hand, is one of the poles around which the drama revolves, the voice of implacable divinities and cruel justice. Between director Mayer’s indifferent staging and a lack of vocal heft from bass Dmitry Belosselskiy, the role of Ramfis was nearly erased in Tuesday’s performance.

In real life, kings can be short and a little stooped and bustle about the room, but one wished baritone Quinn Kelsey had channeled a bit of his inner monarch so that Amonasro, King of Ethiopia, didn’t come across as quite such a trivial schemer. His evocation of the suffering of the Ethiopian people in war sounded hard-hearted and manipulative—a defensible directorial choice, but it made Aida seem like a fool for falling for it.

Rounding out the cast, Yongzhao Yu as the Messenger stoutly announced the Ethiopian army’s advance in Act I, expressing indignation at their atrocities as only a tenor can. Offstage in the temple scene of that act, the clear-voiced soprano Amanda Batista as the Priestess and her chorus of priests wove an exotic spiritual atmosphere.

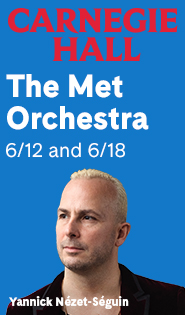

Speaking of exotic atmosphere, conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Met orchestra were generating plenty of it in the pit with harps and delicate tissues of woodwinds. The conductor paced the drama astutely, and was alert to Verdi’s countless indications of “colla voce” (with the voice). The big set pieces came off well, although positioning the “Aida trumpets” in the balcony added to the puzzle of what was going on in the triumphal scene with archaeologists, etc.

Donald Palumbo’s choruses performed superbly throughout, from the fierce diction of the crowd scenes to a mere aural fragrance in the temple.

Set designer Christine Jones’s tall scenery marked off symmetrical rectangular spaces, whose dullness was relieved by Egyptian insignia and Kevin Adams’s lighting effects. Life-size Pharaonic statues in niches gave the archaeologists something to peer at, but otherwise just contributed to the Egyptian wallpaper effect. The relentless symmetry of her design and the regimented blocking of the choruses had an oppressive effect—perhaps intentional on Mayer’s part.

Choreographer Oleg Glushkov, in his Met debut, dazzled with inventive sequences for female and male corps, sinuous and rippling for the former and gymnastic for the latter, and even making child dancers appear to fly in formation.

Costume designer Susan Hilferty clearly had done her homework, although how to dress a princess as a slave is probably not documented in the historical record. (Blue wore simple dresses with a tatter or two to indicate misfortune.) Although the overall ancient-Egypt look seemed right, the Ethiopian captives looked more like ragged street people than soldiers, and dressing Ramfis in black may have contributed to his low profile in this production.

A final note: Verdi specifies that Aida “dies in Radamès’s arms.” On Tuesday, it appeared that Radamès was expiring with his head in Aida’s lap. And was Amneris committing hara-kiri at the final curtain? It certainly looked like it. As long as we’re changing the ending, why not have the two lovers push the stone aside and make a run for it?

Aida runs with the current cast through January 25. Christina Nilsson sings the title role March 14-29 and then Angel Blue April 27-May 9. Brian Jagde sings Radamès March 14-May 9 with Elīna Garanča as Amneris April 27-May 9. metopera.org

Posted Jan 01, 2025 at 8:26 pm by Elizabeth Pomeroy

Wow ! Excellent reviewing of a quirky production (?). Did the archaeologists sing ? There is a fine touch in this reviewing, which I always enjoy. Bravo reviewer, and bring us more.

Posted Jan 02, 2025 at 5:02 am by Scott

The chorus master for this AIDA was DONALD PALUMBO and his stamp of rich, dark, powerful, well-blended choral sound was audible and should be noted and praised!

Posted Apr 25, 2025 at 12:58 pm by daniel guma

I think you are quite lenient on the whole archeologists issue, I think it´s outright idiotic but well adjusted to these times of acknowledgement of whatever went wrong in the past.

As for the “choreography” it was absolutely ludicrous. All that smacked of the Marx brothers.