One-man opera brings time-traveling Beethoven into the 21st century

Beethoven’s late string quartets are still a challenge for performers and listeners, and none more so than the first finale he composed for the Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130. This wild music, bristling with complex counterpoint, so confounded its first hearers that the composer was persuaded to substitute a more ear-friendly finale and publish the first one separately as the Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue), Op. 133.

Like many latter-day musicians, composer Elliott Sharp admired the great fugue’s radicalism and its way (he wrote) of “annihilating the esthetic standards of the day and approaching escape velocity from the gravity of diatonic harmony.”

And he didn’t stop there. He took his space-ship metaphor into the composing studio and produced, with video artist Janene Higgins, Die Grösste Fuge (The Greatest Fugue) a time-travel fantasy of Beethoven interacting with the 21st-century culture he helped to create.

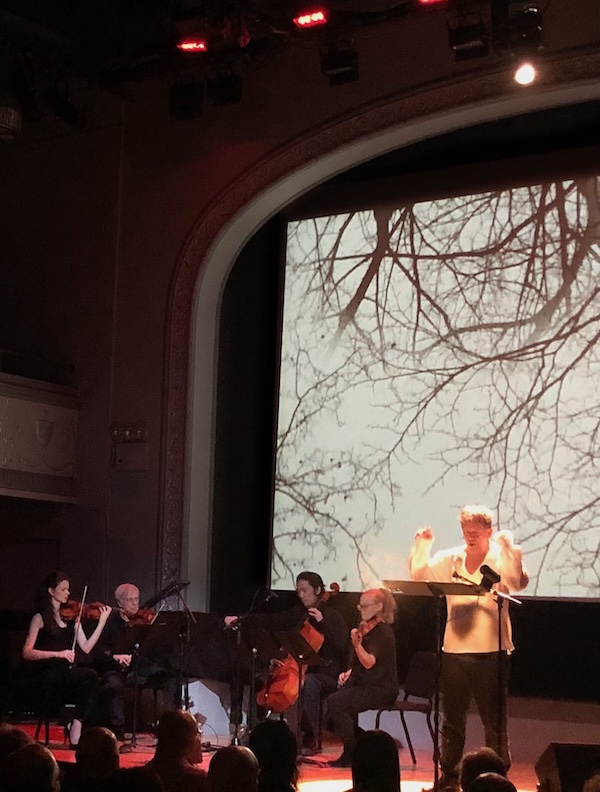

Die Grösste Fuge made an impressive New York bow Thursday night at Roulette in Brooklyn, with a cast of one—bass-baritone Nicholas Isherwood in a flowing ruffled shirt as Beethoven himself—and a string quartet backed by Sharp’s atmospheric electronics.

Higgins’s video projections—swinging from abstract geometry to nature imagery, and from historical pictures to emblems of modernity such as computer code and a mushroom cloud—provided visual counterpoint to Sharp’s libretto, an amalgam of Beethoven’s letters and passages from his favorite poets, Schiller and Goethe.

For anyone who has puzzled over the late quartets and the Grosse Fuge—or even those who haven’t but are up for a centuries-spanning musical-visual adventure—Sharp’s one-man opera will take them places they haven’t been before.

Derived from the Latin for “flight,” the word fugue in music denotes a composition whose themes seem to fly after each other in counterpoint. More recently, the term “fugue state” has meant a psychological condition of flight from reality to an alternate world.

Beethoven’s great fugue seems to partake of both meanings, and Die Grössste Fuge pushed the latter idea several steps further, picturing the great composer—aged, chronically ill, deaf, yet burning with artistic ambition—lifting off from this planet of pain to imagine a world of wonders, inexpressibly beautiful and unprecedentedly violent.

Singer Isherwood was onstage continuously, first tossing and turning on a couch, but soon standing at a tall music stand and singing for most of the opera’s hour-and-a half duration. And not just any kind of singing, but what appeared to be a particularly taxing style of forte marcato declamation on long notes, yanking his fists for emphasis on each syllable.

Relief came with some softer passages and a return to the couch for a few minutes, but overall the role seemed a tremendous test of stamina, which Isherwood passed handsomely, embodying the old composer’s intensity and yearning for transcendence.

Despite his singing in English with amplification, the work’s extreme style of vocalization made distinguishing the words difficult. This problem was mitigated by the fact that, according to composer-librettist Sharp, the texts had been passed repeatedly through AI translation software and “cut-up” to produce a kind of magnetic-fridge poetry version quite different from the originals.

An exception was a passage from Beethoven’s most famous letter, the confessional “Heiligenstadt Testament,” bemoaning his deafness and social isolation, which Isherwood read straight in a fine speaking voice.

And through clear singing and watery visuals, the artists made sure listeners heard Beethoven’s famous dictum on J.S. Bach: “Not Brook (Bach), but Ocean should be his name.”

The continuous performance fell into several sections, distinct as to the character of the music and of the images from Higgins’s rich visual vocabulary, which could be as naturalistic as tree branches and scudding clouds or as abstract as converging lines and a wash of mossy green light.

The four exceptionally able string players onstage—violinists Sara Salomon and Concetta Abbate, violist Ron Lawrence and cellist Hao Jiang—divided their time between blending with the electronic soundscape and performing frenetic atonal scherzos.

In their transparent timbre and eager articulation, the latter pieces bore a family resemblance to Beethoven’s own late quartets. It was easy to imagine the old master composing them himself in a post-Schoenberg, post-Bartók world.

And throughout the work, as in Beethoven’s great fugue, one could sense themes and motives combining, inverting, etc. amid sudden changes of tempo and texture.

At the close, the opera acknowledged that the artist, like all of us, must eventually leave the stage. With a smiling adieu, singer Isherwood did exactly that, leaving the quartet to pronounce an adagio epilogue.

On the big screen, projections recapitulated abstract imagery from the work’s beginning, reminding watchers that the cycle of creation goes on.

This performance has been archived for stream viewing. roulette.org