A strong Met cast vies with the structural problems of Blanchard’s “Fire”

Opera takes time, not just to play out but to get to know. Even compact monodramas have layered and complex details that often can’t be fully grasped in one performance. Such was the case with the pleasure of seeing Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones return to the Metropolitan Opera house Monday night.

With the excitement of sheer newness burned away, this revival of the production that opened the 2021-22 season showed a score that’s a leading example of what American opera can be, even as it is hampered by some substantial obstacles. The story, distilled by librettist Kasi Lemmons from New York Times’ journalist Charles M. Blow’s memoir, both belongs to the 19th century operatic tradition and is very much contemporary and American.

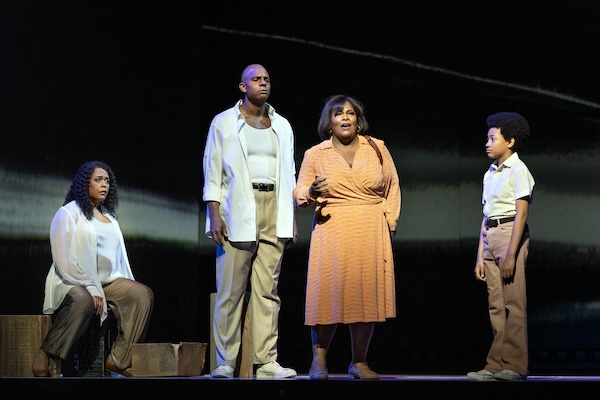

Blow, sung as an adult by bass-baritone Ryan Speedo Green and as the seven-year old Char’es-Baby by young treble Ethan Joseph, comes of age as an outsider in poverty in the South, suffering horrible abuse as a child, searching for identity and a sense of belonging. As in much of Verdi, a murderous vendetta is a key element in the drama, but it resolves in a way that belongs to the opera’s contemporary setting.

The main character of Charles is actually three: himself, himself as a child (often in duet, narrating the same events from two different places in time), and haunted by an internal voice that is both Destiny and Loneliness (soprano Brittany Renee, who also has a small but important role as Greta, in the third and final act). He is surrounded by family, including four brothers, his malevolent cousin Chester (tenor Daniel Rich), and especially his mother Billie (soprano Latonia Moore) and an absent, womanizing, alcoholic father Spinner, sung by tenor Chauncey Packer.

Green is one of the leading operatic performers. He sang with the strength, elegance, and expression one expects from him, and his natural acting and ability to convey moods ranging from silliness to fury made for a compelling characterization that was full of nuance. He was powerful because the character has to wrestle with so many conflicting thoughts and emotions so that one may predominate in any given moment, while the others linger. The duets with his younger self were poignant not simply because it is such an intelligent musical device, but because Joseph was exceptional, with great projection and intonation in his singing, easygoing phrasing, and a confident stage presence.

Renee took some time to get going. The opera opens with dialogue between Charles and Destiny, and Green was full of energy from his opening note, while Renee sounded slightly subdued and stiff. Both her voice and her phrasing opened up as things went along, though, and as Loneliness, her singing was beguiling and supple, while as Greta she captured both the sincerity and naïvete of a young woman who means well but can’t be who Charles needs her to be.

Both Moore and Packer were excellent, scintillating in different ways. Moore’s tone was beautiful throughout, and she modulated her color from dark to light depending on the situation and the character’s mood. Packer was charismatic as Spinner, his voice alone expressing a mix of arrogance, seduction, and pleading. His bright reediness was a welcome element in the darker toned quality of much of the singing and the score.

Blanchard’s score is quite fine and has a style that is important. It’s easy to point to how he mixes popular idioms into a form that’s roughly modeled after Puccini—there’s a jazz rhythm section in the orchestra, all conducted by Evan Rogister—but what he made is the modern, and under-appreciated, studio orchestra. That’s the mix of orchestral instruments with things like guitar and drums that was essential to creating the sound of important modern American popular music, from Gil Evans’ orchestrations for Miles Davis, to musicians like Nelson Riddle and Gerald Wilson writing scores for Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole, Dinah Washington, and Nancy Wilson.

The score has that sound, and it’s a wonderful one, not a hybrid but its own American thing. With Rogister, the orchestra was mostly agile and on top of the stylistic phrasing and rhythms, although some Latin and Afro-Cuban passages sounded awkward in the pit. The flow of the music helps get through the second and third acts, which are hampered by the libretto. Word-to-word, line-to-line, Lemmons’ text makes for good vocal music, especially with Blanchard’s skillful technique.

But the drama is lumpy. There’s plenty of action in Act I, but some scenes pack in large amounts of information, others are languid, and it feels off-balance. The latter two acts move from one set piece to the next. Some, like the “Step Dance,” are spectacular—though that has no words—but each one starts and stops. Everything needs to keep starting, the burden is on the singers, not the story, to keep things moving. Monday, they mostly did, but the holes in the drama diminished the ultimate impact.

Fire Shut Up in My Bones continues through May 2. metopera.org