Noisy “Émigré”casts a monochromatic sidelight on a dark corner of history

Shanghai in the 1930s was the fifth largest city in the world, teeming with an international cast of laborers, traders, hustlers, and, increasingly, refugees from conflicts elsewhere. But World War II came there too, with fierce urban battles and eventually Japanese occupation.

Such was the dramatic backdrop for a tale of star-crossed lovers in Émigré, a sort of East-Meets-West-Side-Story oratorio by composer Aaron Zigman and librettists Mark Campbell and Brock Walsh, which received its local premiere Thursday night with the New York Philharmonic orchestra and chorus and soloists, conducted by Long Yu.

Jews fleeing persecution in Nazi Germany were turned away from many countries, but eventually found a haven in Shanghai’s live-and-let-live multinational enclave—at least until their Japanese overlords forced them to live in a ghetto, an event noted at the midpoint of Émigré.

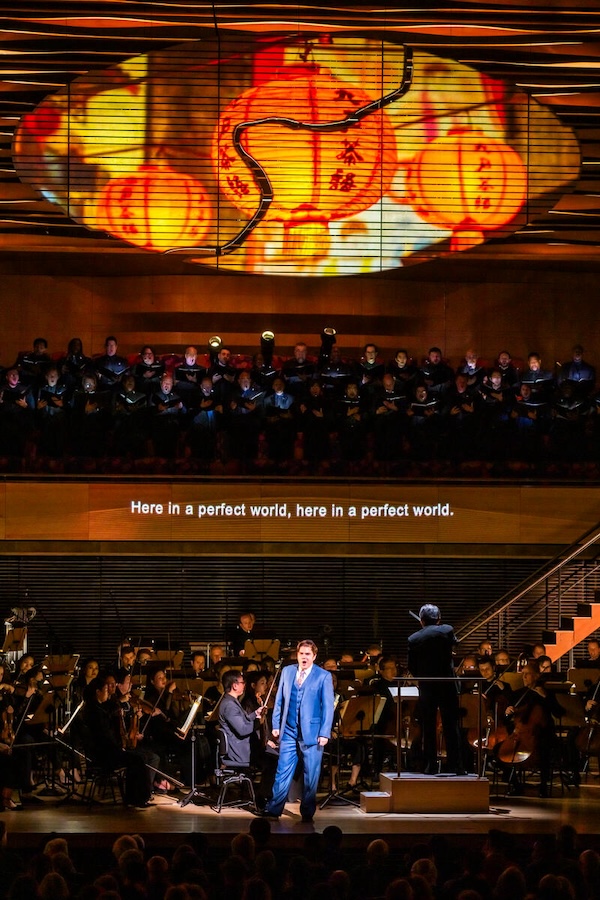

Until that point, it was still possible for a shy young Jewish doctor and a Chinese shopgirl to meet and fall in love, as the characters Josef and Lina did early in this semi-staged performance, resourcefully mounted by director Mary Birnbaum on Geffen Hall’s stage and first tier, with projections by Joshua Higgason.

Their tribulations amid discrimination, cultural clash, and war drove the drama, with a more tradition-minded Jewish couple, Otto and Tovah, as a foil. The even-more-traditionalist fathers Yaakov and Wei, and Lina’s sympathetic sister Li, rounded out the cast.

Long Yu and his Shanghai Symphony Orchestra initiated this co-commission with the Philharmonic, bringing on board the veteran arranger and film composer Zigman, librettist Campbell, and eventually songwriter Walsh to contribute several numbers.

Campbell had previously showed his affinity for people seeking safety in the oratorio Sanctuary Road and the opera Stonewall, vividly characterized pieces about, respectively, African-Americans fleeing slavery on the Underground Railroad and gay people seeking each other’s company before getting caught up in a civil-rights demonstration. The 23 songs in Émigré, however, have to carry a lot of narrative and uplifting message at the expense of fleshing out the characters.

Campbell also had better luck with composers those previous times. Expert in painting emotions in primary colors, master of the cymbal-driven cinematic crescendo, Zigman struggled to produce a memorable melody, instead setting lines of text in homophonic chunks, and reducing Campbell’s inspirational verse to doggerel. (While the singing was mostly in English, supertitles alternated between English and Chinese.) The shapely tune of Tovah and Otto’s love duet “Once Upon a Night” in Act II was a reminder of what had been missing for much of this night.

Musical fusion was not on the menu either, with a pentatonic scale here or a xylophone riff there the only hints of anything authentically Chinese in the score.

Zigman seemed to come from the everything-all-at-once school of orchestral and choral scoring, rarely backing off from lusty tutti to more intimate textures. (A gentle lament for oboe and harp near the work’s close brought long-awaited relief to the ear.) He also used the chorus—well prepared by Malcolm J. Merriweather—too often as reinforcement for the soloists instead of as a distinct musical element.

All or most of the capable cast were reprising their roles in the work’s Shanghai world premiere last fall, and making their Philharmonic debuts. Arnold Livingston Geis brought a full-bodied lyric tenor to the role of Josef, a timbral (and cultural) contrast to the somewhat more slender and piping soprano of Meigui Zhang as Lina. In the mezzo-sidekick role of older sister Li, Huiling Zhu brought vocal warmth and an observer’s perspective to the drama.

As the Jewish lovers Tovah and Otto, soprano Diana Newman’s easy, comfortable delivery contrasted rather starkly with Matthew White’s intense, piercing tenor. Newman’s feminist anthem “In a Woman’s Hands” managed to be, if not a show-stopper, at least a show-pauser.

The two bass-baritone fathers were also a study in contrasts: shawl-draped, slightly stooped Andrew Dwan as Yaakov dispensing wise advice in a startlingly room-filling, resonant voice, and stout, stern Shenyang (the cast’s only Philharmonic non-debutant) as Wei, a rock of hard-toned resistance to anything not Chinese, at least till his grief-stricken lament at the end.

Long Yu, the begetter of this show, led the proceedings with a firm hand, producing a well-coordinated and balanced performance. He could perhaps have found ways to bring more variety to Zigman’s overstuffed score.

The production team was, to a man or woman, new to the Philharmonic. Like the music, Oana Botez’s costume choices dealt in the elementary: earth tones for the Jews, bright floral sheath dresses for the Chinese women.

Apparently, with the orchestra sitting onstage in darkness, lighting designer Yuki Nakase Link had no choice but to light the downstage characters harshly from the side, producing an oddly horror-show effect. At times, Link threw patches of light around the auditorium to hint at a battle going on somewhere, or for more obscure reasons.

Scenic designer Kristen Robinson suggested a home and a shop with bits of furniture downstage. Thanks to the stairway up to the first tier, the lovers even had a balcony scene.

This may be a long shot in our visual culture, but one is tempted to call for a Federal Projections Commission to regulate the use of projections in classical concerts. It’s understandable for narration and scene changes in operas and quasi-operas like Émigré, but even here it can be a distraction, or a crutch when the music isn’t quite hauling the mail. As when Japanese soldiers march onscreen while the orchestra says “bad,” and lovers appear in silhouette while the orchestra says “good.”

The auditorium was packed for the concert, and so, surprisingly, was the hall’s Grand Promenade for the pre-concert discussion. The staff had set up a few dozen chairs, enough for the usual turnout for such events. Instead, hundreds mobbed the vast space to hear the famous panelists: journalist Jonathan Kaufman, who chronicled Jews in Shanghai in his book The Last Kings of Shanghai, and former U.S. Treasury Secretary W. Michael Blumenthal and the longtime Harvard law professor Laurence Tribe, both of whom, as children, were Jews in Shanghai during the period depicted in Émigré. In addition to colorful anecdotes of that time, they said that early experience of discrimination and privation spurred them to spend their lives working for economic justice and constitutional government.

On a similar note, the musical experience of Émigré ended with a plea for peace and brother/sisterhood. May it be heeded as productively as Blumenthal and Tribe did theirs.

Émigré will be repeated 8 p.m. Friday, preceded by a panel titled “Forced Displacement and Immigration.” nyphil.org