Brooklyn Art Song delivers Parisian wit and sparkle with songs of “Les Six”

The New Year was ushered in with the wit, sparkle, and insouciance of Paris in the 1920s by the Brooklyn Art Song Society on Friday evening in a concert entitled “Les Six” at Brooklyn’s First Unitarian Church of Brooklyn.

This was the fourth concert in a series entitled “Circles” which explores through song the relationship amongst composers who were varyingly each other’s friends, enemies, lovers, colleagues, mentors, and inspiration. It was an evening of lyrical delights par excellence, which is always to be expected at a BASS recital.

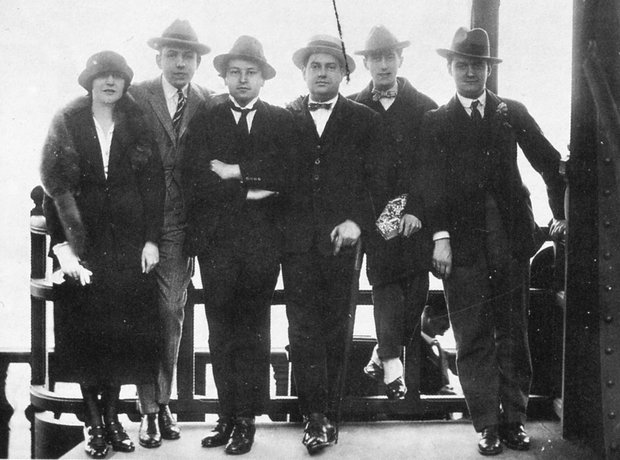

For the composers grouped as “Les Six”—Georges Auric, Louis Durey, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud, Francis Poulenc, and Germaine Tailleferre—it was a case of being in the right place at the right time, rather than an overriding ambition to be arbitrarily anointed as a member of a group of bright, young things. As Michael Brofman, BASS’s founder and artistic director, noted in his opening remarks, “Young, ambitious composers are not particularly focused on collaboration.”

The six composers—five of them French and one Swiss (Honegger)—couldn’t agree among themselves as to how the group originated. What is certain that they all lived in worked in Montparnasse and that the name of the group was coined by Henri Collet. Erik Satie and Jean Cocteau served as older mentors to the group of young composers.

The three song cycles by George Auric, Arthur Honegger, and Louis Durey which opened the program were all composed during the period of time in which Les Six actually functioned as a group. Collectively they all took about seven minutes to perform, their pithiness perfectly in line with Cocteau’s aesthetic sensibilities. The songs’ rapid changes of emotion and pace are reflective of the composers’ fascination with emerging art form of film, in which Cocteau was one of the early pioneers.

Auric composed Alphabet (1921) to poems by Raymond Radiate, a novelist and poet who died at the age of 20 from typhoid which he contracted on a trip with Cocteau. The eight poems which Auric set to music all begin with a different letter of the alphabet.

Soprano Amy Owens and pianist Miori Sugiyama captured the songs varying moods, ranging from whimsy to profound sorrow set to dance-like music, with elan. In addition to her chrystalline soprano, Owen is quite the actress. A gesture as quick and as fleeting as the tilt of her head, coupled with a grin, expressed to perfection the mock serious tale of a dancer who died while standing in her point shoes in “B-ateau.”

Honegger’s 3 Chansons de ‘La petite sirène’ (1926) and Durey’s 3 Poèmes de Pétrone (1918) followed, performed by mezzo-soprano Anna Laurenzo and Brofman. Honegger, who was Swiss, perhaps bristled most at being shoehorned into a group of French composers. His settings of three songs from Hans Christian Anderson’s The Little Mermaid in translations by René Morax, a Swiss writer with whom Honegger would later collaborate on Le roi David, are also prototypical examples of the Les Six style, including his use of bitonality.

Long after Durey had abandoned the principles of Les Six, he would despair that most people knew of him only through his setting of three poems of Gaius Petronius (Pétrone), a Roman poet active in the 1st century AD. After World War II, Durey became a communist, even setting to music poems by Mao Zedong and Hồ Chí Minh—efforts that undoubtedly contributed to his lack of popular appeal.

Durey’s 3 Poèmes de Pétrone are among the purest expressions of the Les Six style. In the songs, he uses small repeated musical units, meant to be the musical equivalent of Picasso’s cubism, to brilliant effect. His choice of poetry dealing with scenes from everyday life, as opposed to loftier subjects embraced by the artistic elite of the day, were also in keeping with the group’s socially conscious sensibilities.

The luscious-voiced Laurenzo enlivened the songs of both composers with her articulation of the text and dramatic flair. Her voice floated effortlessly when singing of the wind and waves in Honegger’s “Chansons des sirens” and displayed warmth and richness in its lower ranges when evoking the gentle rocking of the waves in “Berceuse de sirène.” In the Durey songs, singer and pianist engaged in more expansive, dramatic musical brush strokes, without any loss of precision or subtlety of expression.

Germaine Tailleferre was the only woman member of Les Six. Her musical style encompassed bitonality, jazz, and cabaret rhythms. The composer’s feistiness and feminist sensibilities are expressed in her saucy 6 Chansons Françaises (1930) which take stabs at fidelity and other societal norms.

The task of interpreting these lyrical delights fell to soprano Sara LeMesh and Sugiyama at the piano. Singer and pianist both had the insouciance to capture Tailleferre’s singular style. The final song of the cycle,” Les trois présents,” to a text by Voltaire, displayed both artists at their best in giving life to one of Tailleferre’s grand melodies, topped off by LeMesh’s luscious high notes.

Owens and Sugiyama returned for a brilliant account of Darius Milhaud’s Chansons de Ronsard. One of the most prolific composers of the twentieth century, Milhaud’s legacy is equally assured through the accomplishments of his remarkably diverse array of students, ranging from Burt Bacharach, Dave Brubeck, Philip Glass, Steve Reich, Karlheinz Stockhausen to Iannis Xenakis.

Brofman described Milhaud’s setting of the words of the great French Renaissance poet as being more extreme for the soprano voice than the Queen of the Night’s arias in Mozart’s The Magic Flute and indeed they are. This, however, is a vocal realm in which Owens reigns supreme. She dispatched ear drum-splitting notes in the stratosphere with ease, aplomb, and beauty. Her wit and theatricality were always on display, as was her ability to switch emotional and musical gears in a heartbeat.

Undoubtedly, Francis Poulenc is the most famous composer of the six. He was once described as being “half monk and half naughty boy,” and it is the lighter side of his personality that is on display in his song cycles Tel jour, telle nuit (1937) and Fiançailles pour rire (1939). Both of which were composed long after Les Six had disbanded, but still display Poulenc’s affinity with the group’s guiding principles.

In Fiançailles pour rire, Poulenc set six poems by his friend Louise de Vilmorin, a writer who explored the milieu of the French aristocracy. LeMesh and Sugiyama captured the emotional reserve of Vilmorin’s poetry, which Poulenc musically depicted to perfection with delicacy and exceptional fine attention to musical detail. LeMesh could give voice to the wistfulness in “La Dame d’André” in the loveliest of tones, as winningly as seduction through vocal warmth and languid phrases in “Violin.”

The concert closed with Poulenc’s great song cycle, Tel Jour, Telle Nuit, settings of poems by Paul Éluard. The composer’s affinity with Éluard’s poetry is often compared to that of Robert Schumann’s connection with the words penned by Heinrich Heine. With Brofman again at the piano, the suave baritone Michael Kelly, who won the Poulenc Competition in the early days of his career, sang these songs with empathy and ease.

Kelly’s slightly arch mannerisms were perfectly attuned to the sound of his voice, whether warm and resonant in the opening song, “Bonne journée,” or reduced to almost a whisper in “Une ruine coquille vide.” The wild ferocity which he summoned in “Figure de force brûlante et farouche” was astonishing.

Tel Jour, Telle Nuit songs also found Brofman at his most expressive, with spellbinding playing in “Une ruine coquille vide” (even with an apparently balky piano). The final song of the cycle, “Nous avons fait la nuit,” ends with an extended piano postlude, which Brofman instilled with the requisite touch of ambiguity, bringing closure to this fine concert.

Brooklyn Art Song Society returns with “Circles VI: The February House” on March 1 with the music of Britten and Weill. brooklynartsongsociety.org