Gražinytė-Tyla goes Baltic in Philharmonic podium debut

It is just under a year since conductor Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla and the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra wowed a Carnegie Hall audience with a rich program of Adès, Elgar and Debussy. But if her return to conduct the New York Philharmonic Wednesday in David Geffen Hall couldn’t be described as long awaited, it was certainly, in some quarters at least, eagerly anticipated.

The Lithuanian maestra was emboldened this time to explore less familiar (to Americans) repertoire, surrounding Robert Schumann’s ever-popular Piano Concerto (featuring piano star Daniil Trifonov) with a Baltic sea of music by her countrywoman Raminta Šerkšnytė and Finland’s Jean Sibelius.

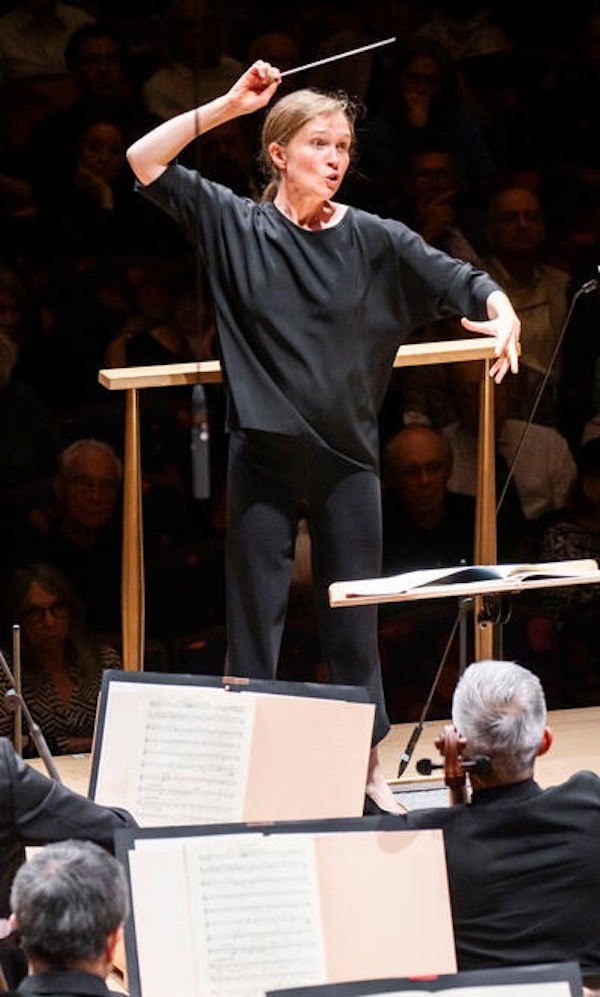

It was all done in her trademark podium style, which managed to be both businesslike and highly expressive visually, her clear beat complemented by eloquent hands and forearms, which are almost musical instruments in their own right, as exposed by the three-quarters sleeves of her black tunic.

As might be expected, her guest-conducting debut with the Philharmonic didn’t always produce the kind of tight coordination and mutual understanding she enjoyed with the players from Birmingham, where she was music director from 2016 to 2022.

And yet a single gesture from Gražinytė-Tyla was all it took to soften or harden the texture in Raminta Šerkšnytė’s De Profundis for string orchestra. Even a listener new to the composer’s music could appreciate the youthful fire of this piece that, according to Rebecca Winzenried’s helpful program note, began as a conservatory graduation exercise but has gone on to become the composer’s most performed work and “a calling card for Baltic music” on the international scene.

What teenager has not thought some version of that Biblical verse, “Out of the depths I cry unto thee”? Turbulent emotion met compositional skill Wednesday night as rushing passages gave way to stretched-out lines, and dramatic pauses punctuated urgent tremolos. It all came wrapped in “the poetic quality and the mystery” that conductor Gražinytė-Tyla playfully calls “Ramintacism.” (The composer was on hand Wednesday to acknowledge applause from the stage.)

Romanticism, the original, was on offer in Schumann’s concerto, perhaps even more than the composer himself intended. Pianist Trifonov set the tone with a volatile performance of the sonata-form first movement that seemed bent on turning it into one of the composer’s whimsical piano cycles such as Papillons or Carneval¸ the playground of his fictional alter egos, impulsive Florestan and dreamy Eusebius.

With fiery passagework and sensitive voicing in the quiet moments, Trifonov made the best possible case for his interpretation. Conductor and orchestra scrambled to stay with his tempo fluctuations, and restored some order in the brisk tutti. Happily, the pianist sat back and let the movement’s poetic cadenza be its wayward self without adding further inflections.

The Intermezzo stayed true to its title, a moment of no-drama introspection in tiptoeing phrases, resisting all temptations to grow big. Woodwinds nostalgically recalled the theme of the first movement, and then it was off to the races with the finale.

“I can’t write a concerto for virtuosi,” Robert wrote to his fiancée Clara. But Trifonov is justly admired for his technique-to-burn, and apparently on Wednesday the urge to turn Schumann’s jaunty Allegro vivace into a virtuoso show was too strong to resist. The result was a good deal of rushing, rhythmic imprecision and skated-over detail for pianist and orchestra alike. But a snappy, well-executed coda made it all right at the end.

For an encore, Trifonov meditatively performed an Allemande in A minor by Rameau.

Sibelius was 30 and just emerging as the musical voice of Finnish nationalism when he composed four tone poems on the adventures of the folk hero Lemminkäinen, the most durable of which is The Swan of Tuonela, with its serene atmosphere and haunting English horn solo. For Wednesday’s program, Gražinytė-Tyla selected three of the four pieces in the Lemminkäinen Suite, bookending The Swan with two lively items, Lemminkäinen and the Maidens of the Islands and Lemminkäinen’s Return.

As told in the Kalevala, the Finnish national epic, Lemminkainen had the good fortune to arrive at an island when all the men were away, and as a result “Nor was there a single daughter,/Not a single mother’s child,/By whose side he did not lie.” Sibelius, it must be said, did not miss a trick in depicting the scene: giggles in the woodwinds, an urgent violin over rumbling brass and bass drum, a highly suggestive crescendo of intertwining lines, and even a little dance amid an afterglow of low brass. Gražinytė-Tyla’s expert management of all this was blunted a bit by blurry execution in strings and winds.

One likes to see orchestra players recognized individually, but bringing the Philharmonic’s English hornist Ryan Roberts to the front of the stage to play his orchestral part in The Swan of Tuonela was a miscalculation. Despite his conspicuous location, this swan appropriately (and deliciously) blended with his colleagues in the orchestral texture, and his part took no concerto-like flights of overt lyricism or virtuosity. A fine performance in the back of the band and a solo bow at the end would have sufficed.

The conductor’s commanding beat and flashing orchestral highlights opened Lemminkäinen’s Return on a note of tension and suspense. Glints of brass, sprays of percussion, and wind swirling through the strings set the nautical scene. There was even a touch of The Pines of Rome (composed 30 years after this piece) in the music’s inexorable momentum over a steady tempo, leveraging excitement through dissonant clashes, a rattle of tambourine and col legno strings, and cymbal crashes, right to the fortissimo finish. No problem getting the musicians to play together for this one.

The program will be repeated 7:30 p.m. Thursday, 11 a.m. Friday, and 8 p.m. Saturday. nyphil.org.