A strong cast rises above Alden inanities in Met’s “Ballo”

Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera returned to the Metropolitan Opera in David Alden’s baffling new production. Whatever this revival lacks in coherency, however, is outweighed by the fine cast which the Met assembled under the baton of Carlo Rizzi.

The action is set in Stockholm in what appears to be the 1930s. Alden’s stab at a unifying visual component is Merry-Joseph Blondel’s Fall of Icarus, which adorns a ceiling at the Louvre in Paris. The link to the plot of the opera is tangential at best, though King Gustavo’s illicit love for Amelia did bring him crashing to earth.

Alden’s fascination with Expressionism and its dark, moody, anti-realism sensibilities lies at the heart of this production. From its beginnings in 1920s Germany, Expression took root in Hollywood a decade later in horror moves and film noir. It’s an aesthetic completely at odds with Verdi and Alden does little to bridge the gap.

A large, worn leather chair to the side of the stage, upon which Gustavo is sitting when the curtain rises, is a key visual element. Moving it about in the final scene takes an impressive amount of effort. Renato has a similar one in black at his home. Metal desks and chairs are also carted onto the stage. In the opening scenes, there is a sense that the action is unfolding in a used-furniture warehouse or abandoned office space.

If that isn’t enough of a visual mashup, the mass of people on stage added exponentially to the disorder. Dancers attired like Fred Astaire twirl about one moment, to be replaced by the men of the chorus in drab brown Nor’easter hats and raincoats a few minutes later. Icarus, however, is always looming above.

Amelia goes to gather the herb, which Ulrica advises will help soothe her trouble heart, in a foreboding place with sinister figures slithering about. She doesn’t need to exert much effort in finding the plant as it is appears in a hand that rises from the depths. Eventually a desolate landscape with dilapidated telephone poles and sagging wires comes into view, evoking a particularly bleak Scandinavian midsummer night.

The room in Renato’s house, where Amelia pleads to see her son one final time and the plot is hatched to murder Gustavo, is all angular black and white Art Deco. The furnishings are sparse, as apart from the chair, there is only an urn, from which the Amelia draws the name of the man fated to murder Gustavo. Hanging on the wall is a beaming portrait of the king, which Count Horn defaces in remarkable spasms of fury and delight.

Gustavo is murdered against the backdrop of a gray and white architectural print of a cavernous Neoclassical interior. The masked ball is a wild party with dancers executing mechanical movements with the utmost of precision. Count Horn is seen writhing on the floor, apparently getting a lashing from a dominatrix. The mayhem subsides for the final moments of the opera with the king forgiving his murderer, Renato, and assuring his best friend that his wife was innocent and faithful to him.

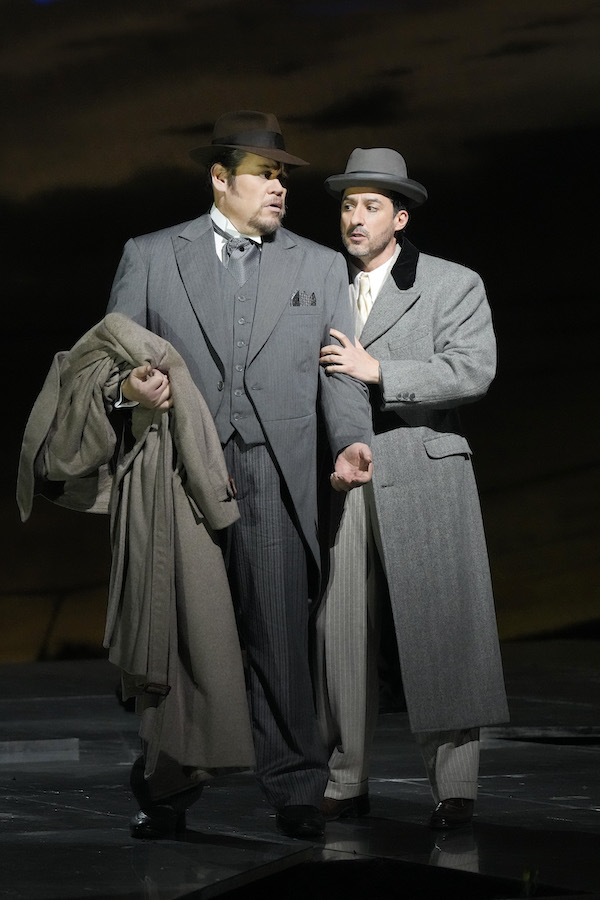

Alden’s concept may have been a grab bag, but the casting was not. Charles Castronovo made an exciting role debut as Gustavo. He cut a dashing, nonchalant figure, with his rich Italianate-tinged tenor throbbing with passion. Angela Meade was in sumptuous voice as Amelia. She filled out Verdi’s soaring lines with plush sound, often topping a phrase with soft, shimmering high notes. As an actress, she made for a sympathetic woman torn between fidelity to her husband and passion for Gustavo in grand operatic style.

Quinn Kelsey unleashed his baritone in a powerful “Eri tu,” which prompted the loudest and most exuberant ovation of the evening. The singer has evolved into a compelling actor, who gets to the emotional core of a character both dramatically and vocally. In sparkling jet black, Olesya Petrova was a chic fortune teller, revealing Ulrica’s prophesies in her plummy, dark mezzo-soprano.

Liv Redpath made a winning debut as Oscar. Sporting Icarus’s wings, Redpath cavorted elegantly about the stage and dispatched trills and coloratura effortlessly in her creamy soprano. Met regular, Christopher Job, was his usual stoic self until overcome with fits, seizures and spasms. Sonorous and sinister, Samuel J. Weiser rounded out the trio of conspirator as Count Ribbing.

Rizzi turned in another of his detailed stylish performances. He paced the drama expertly and was ever attentive to balance. His rapport with the Met orchestra is obvious and they respond brilliantly to his touch. The chorus was in fine form too, with the men being particularly impressive in the scene where Ulrica reads the king’s fortune.

It was a puzzlement as to why the dancers were even on stage, but they certainly added more than a dollop of style and frenetic energy to the bizarre production. And what would Verdi be without a bit of showbiz razzmatazz? Verdi.

Un ballo in maschera continues through November 18. metopera.org