In Met debut Blanchard’s “Champion” proves lightweight in its class

Champion, the first opera by Terence Blanchard, composer of Fire Shut Up in My Bones, made its eagerly anticipated Metropolitan Opera debut Monday night to warm applause. In the end, however, the Met’s gamble—following up the success of last season’s Fire by staging the composer’s rookie effort—didn’t quite pay off.

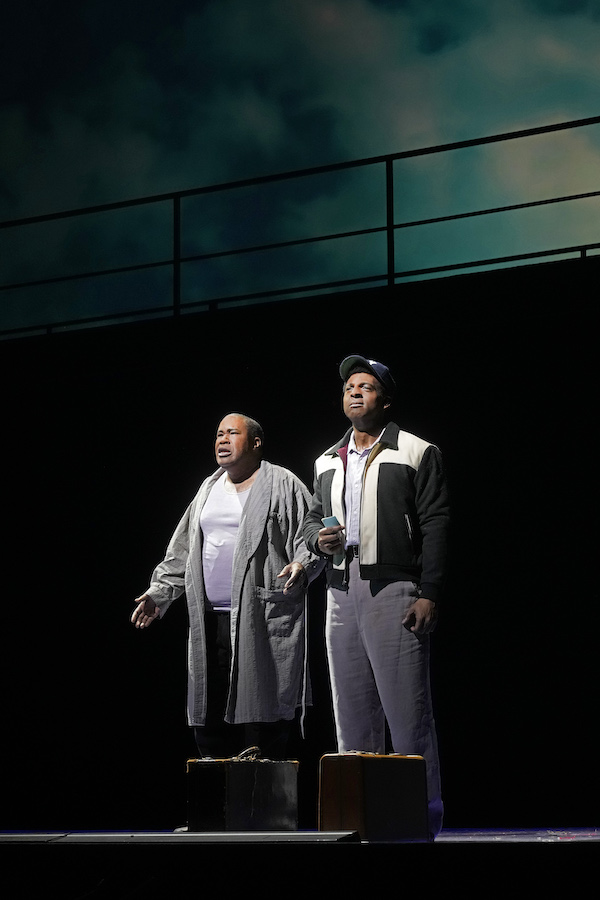

The production had a lot going for it: the good will (and expanded audience demographics) generated by Fire, the first opera by an African-American composer ever produced by the Met; a life-and-death story ripped from sports headlines; the reunion of Fire’s production team of director James Robinson, choreographer Camille A. Brown, and conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin; a highly capable cast led by not one but two esteemed bass-baritones, Ryan Speedo Green and Eric Owens, in the role of boxer Emile Griffith, who won his welterweight title by inflicting fatal injuries on his opponent; and the Met’s vast scenic and costuming resources.

But all of these elements were able only intermittently to breathe life into a libretto and score that spent more time telling listeners how to feel than making them feel that way. Blanchard’s fine ear for scoring and his way with a groove led too often to the orchestra’s riffing idly while singers intoned librettist Michael Cristofer’s leaden phrases (“I can’t give you what you want. Only you can give you what you want.”) The composer literally stopped the show for the show-stopping arias, as if offering opera fans a bauble before getting back to the business of explaining about guilt and redemption.

Not every opera composer can be Wagner, but a recognizable tune or motive here and there could have done a lot to involve the listener and convey the meaning of the action in music, not just words. Even so crucial a moment as that fateful 12th round of the championship bout was marked simply by a generic orchestral crescendo as Griffith rained punches on the defenseless Benny “Kid” Paret, and a life-altering event became just a few seconds of stage action.

Opera is spectacle, and in the best case the eye candy also advances the story. The hero’s college hijinks in Fire fit the plot better than the West Indian festival and the gay bar scenes do in Champion, the latter sticking out for their extravagance and tacked-on feeling. But the fantastic costumes (by Montana Levi Blanco, in a splashy Met debut) and stilt-walkers of St. Thomas were fun, and maybe, just maybe, making a satirical point about the contrast between the rosy tourist view of the Caribbean and the poverty young Emile was escaping.

The bar scenes, presided over by Stephanie Blythe in a nasal character voice as the potty-mouthed proprietor Kathy Hagen, shimmied with dancers and drag queens, and featured the smooth-voiced Edward Nelson in his Met debut as the anonymous Man in Bar, putting some moves on Green as the young Emile.

Choreographer Brown contributed to the action at other points, the most memorable being a troupe of male dancers in boxing shorts and gloves, who mastered the boxer’s wary crouch and lightning jabs better than the two contenders in the ring.

One of those two was Eric Greene, making a double Met debut as the arrogant, doomed Cuban boxer “Kid” Paret and later as his milder-mannered son Benny Jr., to whom the older Emile reaches out for forgiveness. Greene’s woody baritone served both characters well.

The other was Ryan Speedo Green, familiar to Met audiences from fine performances in supporting roles, now stepping up to a leading-man part as Emile. His statuesque presence (slimmed down to fighting weight for the role) and round, resonant voice could carry this heavy show if anyone could. Although composer Blanchard has an imperfect grasp of the arc of an aria, Green still found expressive gold in Emile’s soliloquy “What makes a man a man?”

Eric Owens was effective as a husky-voiced, confused old Emile struggling with physical tasks like putting his shoes on (helped by his patient son Luis, warmly sung by Chauncey Packer) and also with guilt over Paret’s death.

Soprano Latonia Moore, in the complex role of mother Emelda Griffith, who leaves her children behind in St. Thomas but wants to run Emile’s life when reunited with him, made the most of the bel canto flourishes Blanchard wrote for her. Her vocal and physical presence tended to dominate any scene she was in—quite appropriately, as the psychological portrait of Emile took shape.

Blanchard clearly also believes the child is father to the man, since both of his operas feature a very young version of the protagonist. In Champion Little Emile, stoutly sung by boy soprano Ethan Joseph, was seen and heard hoisting a concrete block over and over as penance for “letting the devil get into him,” an experience that would equip him for the ring with powerful muscles and deep resentment.

Tenor Paul Groves brought a kind of urban dynamism as Emile’s discoverer and trainer Howie Albert, but the role’s potential as Svengali or father substitute was not explored in the libretto. That, some awkward vocal writing, and perhaps Groves not being in his best voice, robbed Howie’s big post-fight aria of dramatic impact.

Brittany Renee, on the other hand, was in lovely voice as Sadie, the waitress whom Emile, momentarily distracted by her flirty charm, impulsively married. Later, left at home while Emile went to the gay bar, she wrapped her pearly soprano around her lonely aria.

Lee Wilkof, making his Met debut in the speaking role of the Ring Announcer, appeared often during the stage action, mostly to fill gaps in the story. His mastery of the announcer’s peculiar, barking diction made one think of the role as a musical opportunity missed.

Set designer Allen Moyer used projections to turn a catwalk and sliding panels into a Caribbean isle, a block in the Bronx, old Penn Station, and a leafy city park. (A bar, a sofa, a boxing ring slid in and out as needed.) But dwarfing the performers with giant projected boxing photos and newspaper headlines uncomfortably recalled the Jumbotrons that now plague live sports events.

Conductor Nézet-Séguin easily slid into Blanchard’s groove, supported by a jazz rhythm section consisting of pianist Bryan Wagorn, bassist Matt Brewer, guitarist Adam Rogers, and drummer Jeff “Tain” Watts. Although the opera felt like every minute of its three hours, the conductor’s execution and pacing were beyond reproach.

Champion runs through May 13. Met in HD in cinemas April 29. metopera.org.

Posted May 01, 2023 at 7:20 pm by Agnes Habony

Compelling production of Champion was powerful with insightful revelations about human nature. It had an emotionally evocative ending that left me in tears.