Met’s “Akhnaten” returns and rises to even greater heights

The Metropolitan Opera’s revival of Philip Glass’s Akhnaten opened Thursday night, with countertenor Anthony Roth Costanzo again in the title role of the Egyptian king who tried to establish monotheism—now a happily familiar musical thrill in New York. The fate of contemporary opera is always precarious, but the popular success of this Phelim McDermott staging was so great when it first appeared in the 2019-2020 season that reviving it so soon was an easy call.

Having this as part of the Met’s regular repertoire is a great benefit to opera lovers and the classical music world in general. With repeated exposure, the brilliance of this score comes into sharper and more heightened focus, as does the certainty that Akhnaten is one of the great traditional operas, albeit in a “modern” compositional style. As Monteverdi reflected the musical world of his era, so Glass has done since the late 20th century.

Costanzo sounded magnificent. The role seems so ideal for him that he appears to grow in stature on stage, not only when naked but clothed in Kevin Pollard’s extravagant and elegant costumes. His voice sounded fuller, more penetrating and even more beautiful than in his earlier appearance this season at the Met in Rodelinda. LINK In the sole aria-like passage in the piece, the “Hymn to Aten” in Act II, the way he shaped phrases and dynamics was lovely and musical, and the sound of his voice had an exceptional blend with the orchestra.

As it also did with mezzo-soprano Rihab Chaieb, new to the production, who played Nefertiti. The two have a fabulous, nearly wordless love duet in Act II, and the colors of their voices mixed together with something like different hues connected on a spectrum. The symbiosis between the pair is echoed on stage in the identical red robes they wear, each trailing off into the respective wings. This seamlessness in the production, in and with the score, comes through with repeated exposure and was one of the added pleasures Thursday night.

With Constanzo, Chaieb, and soprano Disella Lárusdóttir’s shining voice as Queen Tye, the principal singers all lie in close range and their harmonizations were like a mirror enhancing sunshine.

Conductor Karen Kamensek was back in the pit, leading superb performances from the orchestra and chorus. The balances between voices and instruments, and within the orchestra, were terrific. Glass’s repetitive structures are well known, but an underrated and vital part of his music is his sound, the way he emulsifies similar and disparate timbres into a rich, liquid surface, with subtle waves of color rising and falling. This sound Thursday night was excellent, even on top of the sharpness of the playing and singing, the sense of both concentration and easy flow. In Act III, as the drama came to its climax, the playing and singing were as fiery as one will ever hear at the Met.

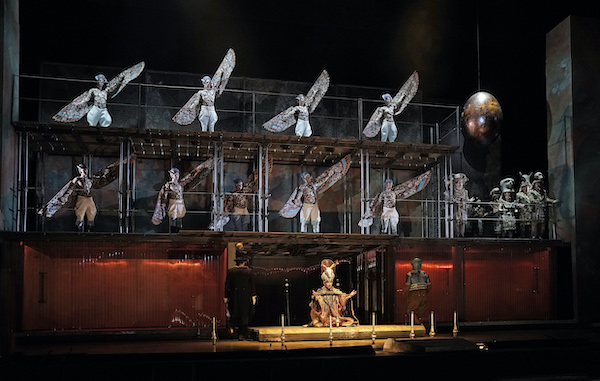

Akhnaten’s musical power was to the fore Thursday, but also how the greatness of this work and McDermott’s production fit into the storied opera tradition. There is a lot of music in Akhnaten but not a lot of singing in terms of most operas, and while there is a story, there’s almost no libretto. But it doesn’t need one, the music displays the drama so well, and except for “Hymn to Aten,” there is no singing in English (nor does the Met use back-seat titles for this). Combining choreography, blocking, and juggling, the direction creates a physical counterpoint to the music. The skills ensemble pantomimes things like ejecting the High Priest (tenor Aaron Blake, cutting through to the back of the hall) from his temple, and their juggling punctuates the rhythms, phrases, and cadences in the score, much like how Mark Morris creates a dance.

The other main character, Amenhotep III, Akhnaten’s father, is a non-singing role, played again by bass-baritone Zachary James. The part, and James’ performance, is one of the most vibrant and thrilling things about the opera. As a ghost, Amenhotep narrates his own soul’s ascension to heaven, and then interleaves poetic descriptions of key scenes, such as Akhnaten establishing his new city, or the reasons Egypt revolts against the new king. James’ vocal charisma and physical presence (especially delivering his part while holding Constanzo in his arms like a child for several minutes) were gripping and intellectually stimulating.

Close to the end, James appears as a university lecturer, giving a modern introduction to the ruins of Aten. There’s a charm to this, and it’s also dramatically incisive, setting up the vocal epilogue where the spirits of Akhnaten, Nefertiti, and Queen Tye come together once again in a near-literal haunting from the past—a deep history that Glass and this production make live again.

Akhnaten continues through June 10. metopera.org