Met offers an inspiring reprise of new “Rigoletto”

Bartlett Sher’s production of Rigoletto has returned for five performances to close out the Metropolitan Opera season. When it premiered last New Year’s Eve, Quinn Kelsey garnered universal acclaim for his portrayal of the title role. If anything, Kelsey’s Rigoletto has become even more nuanced and fascinating in the intervening months, which is raised to even greater heights in this run by the exquisite Gilda of Erin Morley.

Premiered in 1851, Rigoletto was Verdi’s sixteenth opera, which together with Il trovatore and La traviata, established him as the undisputed master of the genre in Italy. Based upon Victor Hugo’s 1832 novel, Le roi s’amuse, the plot centers upon the dissolute Duke of Mantua, his court jester Rigoletto, and his daughter Gilda, who sacrifices herself for love. The opera was an immediate hit, so much so that its most famous aria, “La donna è mobile,” was already being sung in the streets the morning after the opera’s premiere in Venice.

Sher updated the action from 16th-century Mantua to the Weimar Republic in the 1920s, but there is little to anchor the events in time or place. The sleek Art Deco esthetics that Sher employed for the Duke’s place would have pleased up-and-coming fascist leaders, while Rigoletto’s home and Sparafucile’s tavern are plain and functional. The rotating set’s chief asset is that it is a fine acoustical shell which displays the singers’ voices to their best advantage.

There is no tinkering with the action until the final act, where Sher veers into the twilight zone. First, when Gilda returns to Sparafucile’s tavern disguised as a man, she is already inside it when her knocks on the door are heard. There is an indication that something supernatural is at play as the stage is flooded with red light. Later, Rigoletto is already mourning his daughter’s death while the canvas bag in which she lies is yet to be opened. No real harm done, but those two lapses are head-scratchers in an otherwise effective and thought-provoking production.

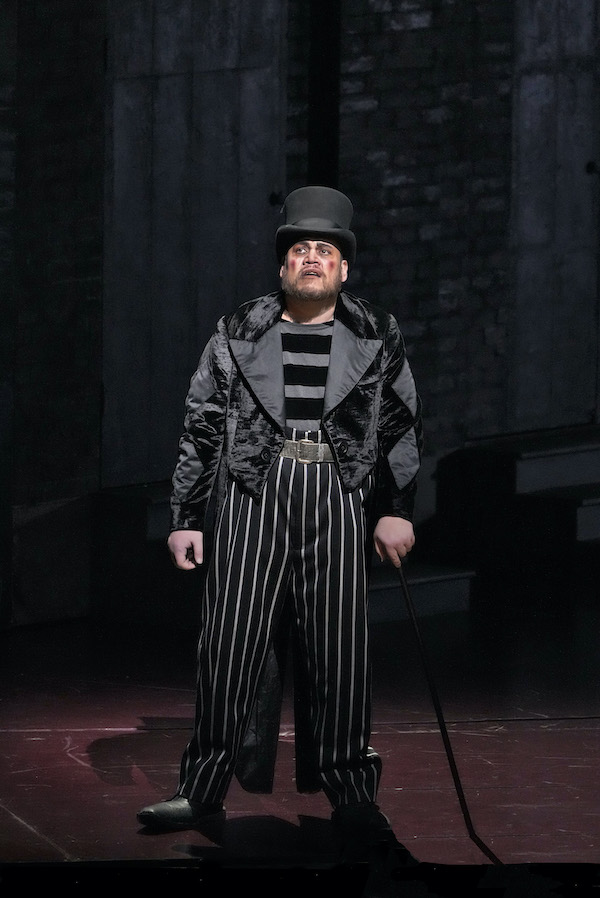

For all of the detail that Quinn has worked into his characterization, it is the beauty and power of his voice, coupled with his seamless legato, that make for such an impressive Rigoletto. With an intentional cough to clear his voice, it is clear that this Rigoletto is preparing for a performance as he enters a door to the Duke’s palace during the brief overture. This is a role that Quinn plays with unalloyed malevolence, but it is in his duets with Morley’s Gilda that his true character, that of a loving father, is revealed.

Morley’s Gilda is a radiant creation that sparkles both vocally and dramatically. The flawless coloratura, pinpoint staccato, and stunning high notes, made for a lovely “Caro nome,” but it was her moving duets with Quinn’s Rigoletto and Stephen Costello’s Duke that made her Gilda so memorable.

As the Duke, Costello sings splendidly with gleaming tone and absolute ease. His “La donna è mobile” is a showstopper and he vocally dominated the famous quartet which followed. The only thing missing is the charisma that makes the Duke so dangerous and alluring: Costello’s Duke seems more of a calculating businessman than self-absorbed, indulgent princeling.

Ante Jerkunica as Sparafucile and Yulia Matochkina as Maddalena made impressive house debuts. Jerkunica’s Sparafucile was tall, lean and menacing, with a commanding bass complete with chilling, cavernous low notes. Voluptuous of voice and figure, Matochkina brought ripe sensuality, glamour and sincerity to Maddalena who, like Gilda, loves the Duke in spite of his duplicitousness and depravity.

Craig Colclough, who here bore an uncanny resemblance to the Italian patriot Giuseppe Garibaldi, was a particularly impressive Monterone. As Murullo, Jeongcheol Cha sang with the forthrightness that he has displayed all season in any number of comprimario roles. The same holds true for Christopher Job and his imposing Count Ceprano.

Conductor Karen Kamensek is demonstrating her mastery of musical styles as divergent as can be imagined in alternating performances of Philip Glass’s Akhnaten and Rigoletto. In a performance that was notable for its rhythmic vitality, Kamensek also let Verdi’s beautiful melodies unfold with beauty and spaciousness. The orchestra responded in kind, playing with exuberance and lending the score a transparent sheen. The men of the Metropolitan Chorus were also superb, particularly in Act II as they tormented Rigoletto, just as he had mocked so many others.

When Kamensek took her solo bow, bouquets of flowers were tossed at her, which Morley helped her gather. There was a moment’s hesitancy as to whether or not the cast should take yet another bow, but with a smile and a nod the conductor led the way. This Chicago native is winning hearts in New York City.

Rigoletto continues through June 11. metopera.org