Drama and strong cast, undermined by sound, fury and duration in Met’s “Hamlet”

Brett Dean and Matthew Jocelyn’s Hamlet has arrived at the Metropolitan Opera. The opera premiered at the Glyndebourne Festival in 2017 and its North American premiere has been eagerly anticipated.

In the Met’s production, unveiled Friday night, Shakespeare is well served dramatically. Dean and Jocelyn have crafted a gripping story from the tragic tale, which is given life by an excellent cast. There are structural and musical elements in the performance, however, that undermine its impact.

Born, raised and educated in Australia, Dean played violin in the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra from 1985 to 1999, until deciding to pursue a career as a freelance performer and composer. His music is championed by leading conductors and orchestras worldwide. Jocelyn, the former artistic and general director of Canadian Stage, the largest not-for-profit theatre in Canada, wears many hats, including those of director and librettist.

Composers and librettists are drawn to Shakespeare’s plays, but success can be illusive. Dean and Jocelyn had leeway as Hamlet exists in three versions, so fidelity to a sacrosanct original wasn’t a concern. Their opera retains roughly a fifth of the original play set forth in 12 scenes, but while the drama is streamlined, little essential is missing.

This still leaves seven main characters: Hamlet, Ophelia, Claudius, Gertrude, Polonius, Laertes and the Ghost of Hamlet’s murdered father—as well as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, a troupe of players, a gravedigger and Horatio—to populate the stage.The impressive feat is that all of these characters are vividly etched and that coherency is maintained throughout the opera.

Dean and Jocelyn also came up with an ingenious device to deal with the play’s most immortal lines, which even if people don’t know the source, nonetheless recognize instantly. The opera opens with a disoriented Hamlet reciting the words “…or not to be” followed by many of the most famous lines of the play. For those hoping to hear those great speeches as arias, this may come as a disappointment. However, as a dramatic expediency, it is brilliant.

There is little visual interest in the production imported from Glyndebourne. Ralph Myers’ set is a formal, white eighteenth-century room devoid of decoration. As the opera progresses, the room is fractured and reconfigured to reveal the reverse of the sets, which is nothing but lumber and canvas. Descending from above, the grave digging scene, nothing more than a pile of dirt, is a visual highpoint.

The women of the Danish court are attired in haute couture creations that evoke the 1950s, while all the men except Hamlet, are in black tie. Claudius wears an impressive crown and Gertrude, his queen, a sparkling tiara. Hamlet opts for a black T-shirt, jeans, pea coat and sneakers. The troupe of players are colorfully, and slightly outrageously, costumed.

Dean’s score is a sonic experience. Musicians are placed throughout the theater, most visibly percussion players in the first three boxes in the Grand Tier on either side of the proscenium. He also places eight members of the chorus in the orchestra pit that serve to amplify and comment on what is being sung on stage.

Electronics, as well as an exotic battery of unusual instruments include an accordion, sandpaper, a Japanese singing bowl played by swirling marble inside, and a tam-tam rubbed by a rubber ball with the pitch electronically lowered a few octaves. Dean describes the latter, as being “the creepiest sound imaginable.”

The opera begins quietly but grows into the sonic equivalent of a maelstrom of words and sounds. As the scene progresses, Dean employs massive, dense orchestral textures that create an oppressive sense of dread, but also incoherency. The great lines of the play were practically inaudible at this performance in an opening scene that left one exhausted and overwhelmed.

Some of the blame has to rest on the shoulders of conductor Nicholas Carter, who was making his Met debut with this performance, but the density is in Dean’s score. It came as a relief that the orchestral textures thinned and the volume levels decreased after the initial onslaught. The score isn’t laden with melodies, but Dean is effective at setting text in a parlando-like manner, and he often employs the spoken word as well. After the initial bombast, almost every utterance could be understood.

Key members of the cast were reprising their roles from the original Glyndebourne production. The exceptions are John Relyea, who was triple cast as the ghost of Hamlet’s father, a player in the troupe of actors and the gravedigger, and Brenda Rae as Ophelia. Relyea was superb in all of his guises and especially witty and wry as the gravedigger, who is preparing Ophelia’s grave and happens upon the scull of Yorick.

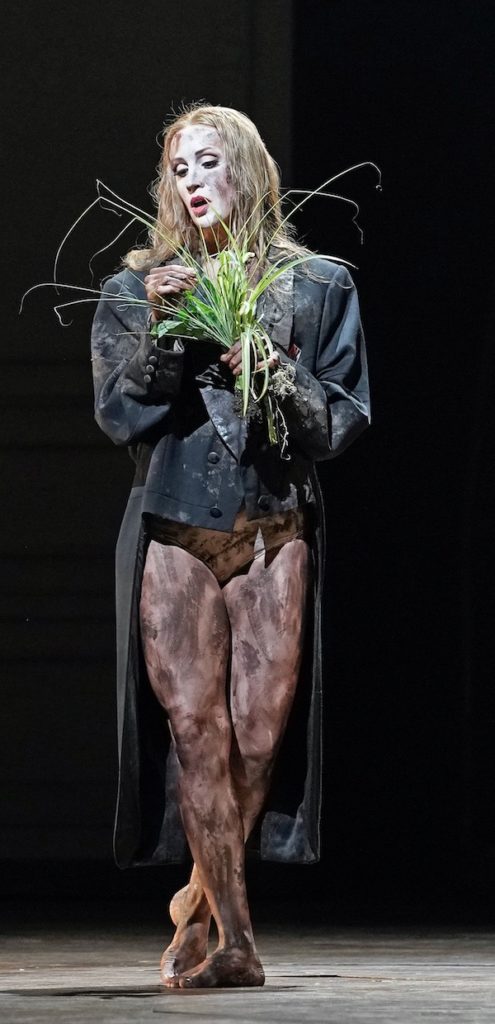

Rae’s Ophelia, a vision of loveliness and innocence in pale peach flounces, was unhinged from the beginning and it was but a slight descent into total madness and suicide. With her mesmerizing stage presence and crystal-clear voice, Rae, covered in dirt, dressed in tatters and clutching a clump of willow branches, galvanized the audience’s attention in Ophelia’s extended mad scene.

Allan Clayton’s Hamlet was also well down the path to insanity from the start. Learning of his father’s death at the hands of his uncle, merely pushed him over the edge. Clayton’s identification with the role is complete. He is a rare opera singer to whom the spoken word is produced as naturally as sung passages. Clayton’s Danish prince provides a good indication of what to expect when he returns to the Met next year in the title role of Britten’s Peter Grimes, with Carter again conducting.

As Gertrude, Sarah Connolly is imperious and aloof, to whom death comes as a surprise. Dean’s angular setting of ‘There is a willow grows aslant a brook’ is the first indication that Gertrude has a heart. Rod Gilfry’s commanding, duplicitous Claudius is sure of both voice and stature. Trumpet fanfares mock his every appearance. Too frequent repetitions of Polonius’s descriptions of Ophelia as a “Green Girl” are grating, but help to define William Burden’s unctuous, eager-to-please courtier.

David Butt Philip’s Laertes and Jacques Imbrailo’s Horatio are the only mentally balanced characters on stage. Philip cuts a dashing figure vocally as well as athletically when engaging in his duel to the death with Hamlet. Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are realized as simpering, obsequious dupes, whom countertenors Aryeh Nussbaum Cohen and Christopher Lowrey perform with unalloyed zest and glee.

Once past the opening scene, Carter never faltered in maintaining balance and clarity. Dean puts as much, if not more, drama in the orchestral writing as he does in the vocal parts. When it comes to color, precision and clarity, the Met orchestra is in its element and delivered here, as did both the on- and off-stage choruses.

Clocking in at over three hours, with one intermission, the opera is as unwieldy as most productions of the play. Opera doesn’t need to be an endurance test. By the end of the first act, which runs for 105 minutes, the audience was getting restive. Standing near an exit at intermission, a small, but steady stream of people left, not to return. Since heeding Polonius’ oft-repeated words regarding brevity wasn’t in the cards, surely another break could have been inserted to lighten the load.

Hamlet continues through June 9. metopera.org

Posted May 18, 2022 at 8:53 pm by CastaDiva

But why the large banner outside the Met showing Laurence Olivier as Hamlet, holding Yorick’s skull?