A starry cast delivers an imposing, powerful “Don Carlos” in belated Met premiere

The Metropolitan Opera returned from its February hiatus Monday night with the belated house premiere of Verdi’s Don Carlos in the original, five-act French version. The trimmed, Italian version, Don Carlo, has been presented at the Met several times—Don Carlos, never until this week.

This is an enormous work, and the complexity of ideas makes it feel even more sprawling than it already is. There are five principal protagonists in a drama with a duration of nearly five hours.

This epic evening began with an unexpected but powerful prelude. Don Carlos is one of Verdi’s small but potent set of operas about political ideas and conflicts, like La Forza del Destino, where the characters are as much bound by the large-scale mechanisms of society and history as they are responsible for their own agency and fates.

The larger world events were manifest to everyone in the house Monday night. General Manager Peter Gelb stepped out onto stage before the curtain to ask for a moment of silence to contemplate the war on Ukraine. He was joined by the chorus, in costume, who then, accompanied by the orchestra, sang the Ukraine national anthem. The audience stood, and there was a feeling of great emotion as well as determination in the hall.

David McVicar’s monumental production (with sets designed by Charles Edwards and finely detailed and meaningful period costuming by Brigitte Reiffenstuel), begins with a giant censer swaying over the stage and the slow tolling of a church bell. Under this cover, music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin rose from the podium, and the music began.

This production is the biggest event of the Met’s current season, fronting a stellar cast of not just marquee names but great performers: tenor Matthew Polenzani as Prince Don Carlos; soprano Sonya Yoncheva as his beloved (and eventual step-mother) Élisabeth de Valois; baritone Etienne Dupuis as Carlos’ heroic friend, Rodrigue; bass-baritone Eric Owens as Carlos’ father, King Philippe II; mezzo Jamie Barton as the Princess of Eboli, and in a small but crucial role, bass John Relyea as the Grand Inquisitor. Singer to singer, ever artist delivered gripping, full-blooded, deeply characterized performances.

Polenzani is always superb in Verdi roles, this star tenor managed to combine pure beauty and sweetness with a sense of maturity and even heroism. Polenzani ran a broad expressive gamut, from gentleness to anger, discouragement to mania.

Yoncheva was a fine pairing with Polenzani, her rounded voice carrying different shades against his bright clarity. In general she sang with a slightly understated strength, pacing the character’s development through the five acts. When she reached her Act V aria, “Toi qui sus le néant,” she had built a deep foundation of expression, and her musical artistry—inflection, emphasis, phrasing—was beautiful.

Don Carlos is not an aria-type opera. There are several substantial solo turns, but the point is the drama, the ensemble interacting, and the solo moments are driven by the plot, not performing conventions.

It is not the two leads who get the most, and best, arias, but Rodrigue and Eboli. Barton and Dupuis were both fantastic. The mezzo sported an eyepatch—a historical touch—and a rockabilly hairdo that combined portraiture of the actual Princess with an East Village touch, while Dupuis had a severe high and tight haircut. Both touches affirmed the characters’ qualities—Eboli independent and Rodrigue devoted in service to the monarchy.

The singing from both was tremendous. Eboli is full of personality and dynamic action and Barton reinforced this with vocal richness and power, and a fire that seemed to come from deep within. Her performances of the Act II “Veil Song” carried the entire scene in the garden, which is slack compared with the rest of the opera. Barton’s singing in Act IV, in duet with Yoncheva and in “O don fatal,” was spectacular, ripping through the music with intensity and absolute sincerity.

Rodrigue is the most difficult character to pull off, as he has more plain unadorned goodness than Don Carlos. Dupuis was beyond impressive, pushing past any corniness and fully embracing the character, from his joy at seeing Carlos in Act II to his political idealism in the face of Philippe’s tyranny to his self-sacrifice to try and save his friend.

The heft of Dupuis’ voice and his superb articulation were essential to this, hearing the character so clearly meant seeing Rodrigue’s qualities of duty, love, and self-effacement. This was strong enough, but the production makes a key alteration to Verdi’s idea at the very end of the opera that completes a parallel that the opera is about friendship in the face of terrible circumstances and choices.

The circumstances are driven directly by Philippe through his power and antipathy and indirectly by his own sense of fealty to God and his fear of the Spanish Inquisition. Owens sounded even better than he was earlier this season in Porgy and Bess, with more projection yet a lighter quality to his singing. He has reached a point in his career where there’s an easy quality to his singing, slightly behind the beat, and such a relaxed and grounded presence on stage that he can show the complexity of this character, who seems to wield so much power yet also feels that things are out of his control. His jealousy is clear but what makes this opera work is that Philippe has to choose not to do the right thing and Owens’ sense of experience and resignation made this dilemma work.

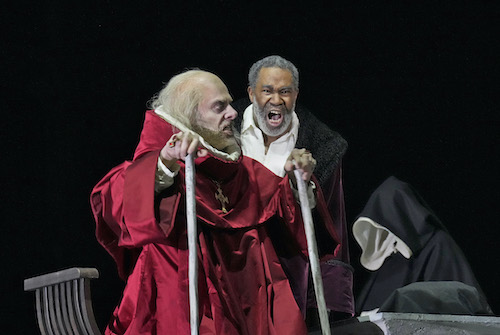

Fundamental to this, and Don Carlos as a whole, is the Act IV scene with the Grand Inquisitor, some of the darkest and most extraordinary music Verdi ever wrote. Relyea sang with gravity and an almost slicing edge to his voice, playing an old man still full of bitter vehemence and command over Philippe. He was dominating, where Owens was almost wistful, and the effect was brooding, complex, sad, and thrilling.

Making all this work was the finest performance one has heard all year from the orchestra, and from the conductor in general. Both in and out of the Met, Nézet-Séquin has been like a hammer all season, pounding away at Beethoven, Aucoin, and most recently Rachmaninoff.

But Monday, the music was full of shades of color and flexibility, marvelous balances, detailed phrasing, excellent pace and phrasing. His typical energy was there, but it was channeled through detail and nuance, and the conductor was comfortable with the spare stretches, and even silence in the music. Whatever funk he has been in so far this season, Monday night it had totally cleared at the conductor was at his finest.

McVicar’s production takes some patience but eventually works well. The censer is evocative but an enormous crucifix, with Christ in agony, is beyond obvious. The sets are creatively ambiguous, enormous walls regularly studded with alcoves. As Adam Silverman’s lighting changes, their colors move from monochromatic gray to brown, with surfaces appear alternately ornate or ruined. Against this, the costumes are gorgeous, and the limited palette turns out to be a frame for some dramatically important explosions of color and bright light, bursts of hope against the darkness.

Don Carlos continues through March 26. Patrick Furrer conducts the March 18 performance metopera.org