Aucoin’s “Eurydice” caught between heaven and hell in Met premiere

At least as far as composers go, Matthew Aucoin is the current public face of American opera.

The subject of an adulatory 2015 profile in the New York Times Magazine (“Matthew Aucoin, Opera’s Great 25-Year-Old Hope”), he is a MacArthur Fellow, and seems to have filled the unofficial music critic role Charles Rosen used to hold at the New York Review of Books.

This is the context in which Aucoin’s Eurydice made its Metropolitan Opera debut Tuesday night. And it’s also the reason why this opera ultimately is so disappointing.

Eurydice is based on the 2003 stage play by playwright Sarah Ruhl, also a MacArthur Fellow, who adapted it for her libretto. The opera premiered last year at the Los Angeles Opera, which co-commissioned it with the Met, and where Aucoin is composer-in-residence.

Considering Aucoin’s exalted reputation, soprano Erin Morley and baritone Joshua Hopkins in the lead roles and music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin in the pit, and advanced press promotion that would be the envy of anyone, one expected something reasonably professional and successful, if not spectacular. But aside from some brief inspired moments, Eurydice was at best functionally mediocre, and frequently less than that.

That was no fault of the performances. Morley and Hopkins both sang with great care—Hopkins had passionate fervor all evening, though Morley was often buried by the score when not singing in her upper register. The supporting performances were even better.

In Ruhl’s reworking of the Orpheus myth, the story is updated to a nameless, general present of beach vacations and high-rise apartment buildings. The narrative follows Eurydice’s marriage to Orpheus, her death and journey to the underworld, and her failed return to the land of the living.

The playwright adds two key twists to the familiar tale: Here, Eurydice dies due to the machinations of Hades, who wants her as his own wife. Also, there is an addition with Eurydice’s deceased father, who writes letters to his daughter from the underworld. The device takes the focus off of Orpheus and his attempt to rescue Eurydice, and moves it to the relationship between her and her father.

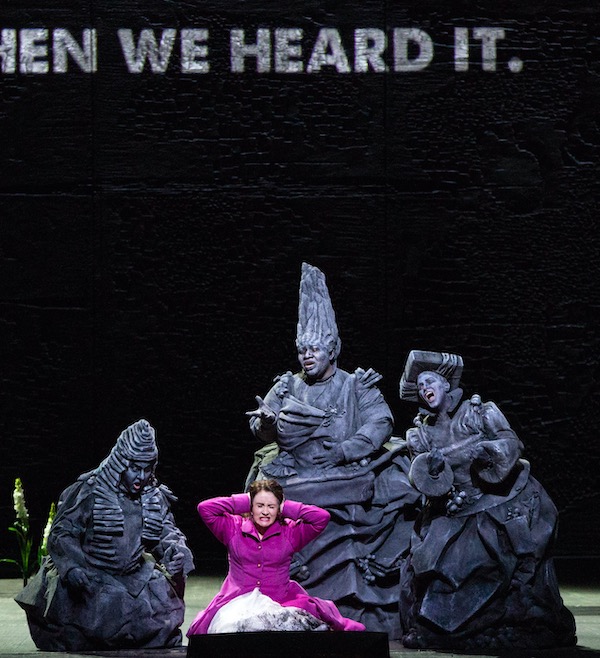

Ruhl’s libretto makes this enticing, since the living remember the dead yet the dead remember nothing, their memories wiped away by passing through a river (a shower or a rainfall, in Mary Zimmerman’s dull and obvious, minimal staging). They don’t even have human language any more, they must speak the “language of stones.” Beyond the plot, Eurydice is the story of the life and death of language.

To say that this could have been a tremendously exciting subject for music, which can juxtapose multiple languages and build entire cultures of it in real-time, is an enormous understatement. And what Aucoin does with this gift from Ruhl is absolutely nothing.

The music is an ultra-conventional cobbling together of elements from John Adams and John Williams. It’s familiar, safe, and so lacking in individuality and style that one cannot even say what Aucoin’s score sounds like after a single hearing. Eurydice is a modern opera based on the Verdi model, but without the Italian master’s color, earthiness, and vital rough edges. (Although tenor Barry Banks was piping, charismatic, and fun as Hades.)

Making his house debut, Nathan Berg as the Father gave the best performance of the night. His bass-baritone sounded constrained at first, but then opened up, following the character’s recovery of his own memories and his eloquence. In the underworld, he teaches Eurydice language again, with the moving help of a book of Shakespeare lowered by Orpheus (the libretto quotes “We two alone will sing like birds in the cage” from King Lear), and with that she remembers her husband and herself. But Berg achieved this with his interpretation; the music doesn’t build to any emotional high point; it just chugs along.

One consistent success in the opera is the pacing, which never lags nor feels rushed, although it is often goosed by the irritatingly gaudy use of snare and hi-hat. But even that was a formal problem—the action moves swiftly but the expression feels shallow; there’s no breathing space in the first two acts to really feel anything.

This does change in Act 3, which was a substantial improvement over the first two. This is where Orpheus sings his way into the underworld—Hopkins singing with real power here—where he finds Eurydice and loses her again. Movingly, her Father steps into the river to wipe away memories of his own despair, and Eurydice recognizes her own loss. The music here allows enough time for these feelings to flower, and Eurydice finally felt like a real music drama.

Eurydice asserts itself as something beautiful, but it feels facile and lightweight as if all beauty requires is major and minor key tonality. Aucoin’s values are conservative, yet he seems uninterested in crafting melodies that say something, building dramatic harmonic tension; plus his heavy orchestration covered so much of Eurydice’s singing.

With the character’s wedding, Aucoin and Ruhl seem to have felt obliged to create a party scene for no other reason than it’s what operas do. This was the weakest point in the opera, with juvenile pop music dance choreography by Denis Jones (in a dubious house debut) over music that had the rhythmic bounce of a cast-iron locomotive. Even Dick Clark knew that you have to give the kids something they can dance to.

Another hoary, would-be innovation reveals the backward-looking artistic values of Eurydice. The part of Orpheus is doubled, with countertenor Jakub Józef Orliński in his Met debut appearing with Hopkins in many scenes. As first introduced, this figure appears to be Orpheus’ internal muse, the voice of a character who is constantly thinking in terms of music. But in practice, his appearances have no clear logic, and he only sings harmony lines—no counterpoint, no antiphony, nothing to add another structural or dramatic dimension. It’s just another musical line in a score that’s already too thick, and another missed opportunity to exercise a little 21st century imagination.

The orchestration is monochromatic and heavy, with few bright colors, the winds barely used for any of their strengths. The Met Orchestra played with the energy typical of Nezet-Séquin’s leadership, but the performance felt unsettled and there were awkward moments in the execution.

Most frustrating for those who care deeply about contemporary music is the sense of a wasted opportunity. The Met is not a place that will produce numerous groundbreaking works with avant-garde ideas, but an artist with the institutional backing that Aucoin has is in a position to take some chances, try some new things, and still be protected from the consequences of failure.

For a 21st-century American composer, the musical world is overflowing with meaningful stylistic and structural possibilities, not the least of which are right in this libretto. That Aucoin produced such a dull and irrelevant work to Ruhl’s masterly word-setting says all the wrong things about the state of contemporary opera.

Eurydice runs through December 16. metopera.org