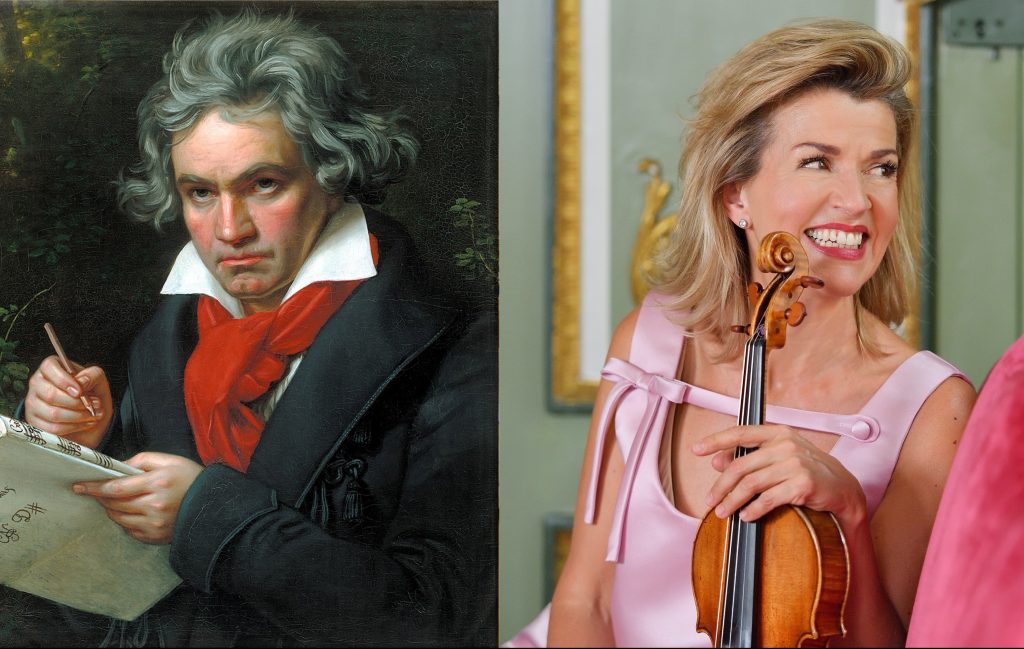

Meet music’s person of the year — and most of the last 250: Beethoven

Beethoven will be 250 years old this December (baptized on the 17th of the month, 1770, he was likely born a day or two prior), and the world of classical music is set to make sure you know it.

In New York City, the locus will be Carnegie Hall, where starting Thursday night with Anne-Sophie Mutter and Friends in concert, there will be 70 events just in the remaining season: from talks and dance performances to a pair of complete Beethoven symphony cycles (from John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique in February and Yannick Nézet-Séguin and the Philadelphia Orchestra, starting in March), a piano sonata cycle from various pianists on both the fortepiano and modern piano, the complete quartets played by the Quatour Ébène, the piano trios, and more.

That’s a lot of Beethoven, and as he is an avatar of classical music and a predictable presence in the concert hall, this is less than welcome for those who gnash against safe concert programming that is a seeming indissolvable crust that covers classical music. As New Yorker classical music critic Alex Ross tweeted: “As much as possible I will be ignoring the Beethoven 250th celebrations since there is nothing more drearily unimaginative that anniversary-driven programming…”

One can endorse the sentiment and the fervent desire to experience more modern and contemporary music, but still recognize that Beethoven is different — so much so that the problem with concert programs is not too much Beethoven, but too little. That is why the Beethoven 250 season is valuable, not because repeated exposure to his music reinforces notions of greatness or canon — it may, but that’s superfluous to what comes through, which is Beethoven’s life-changing importance.

In his era, all music was new and the idea of “classical” didn’t exist. Beethoven’s influence was such that it essentially created that concept. “After Beethoven, the concert hall came to be seen not as a venue for … entertainments but as an austere memorial to artistic majesty,” Ross wrote in an October 2014 look at new Beethoven biographies. From then on, Ross observed, “[M]usic is … accorded powers at once transcendent and transformative[.]”

The outsider

That is historically accurate while also missing something that is essential to music in general and Beethoven in particular. As Ted Gioia shows in his recent book Music: A Subversive History, since prehistoric man gathered around cave paintings to make music, transcendence and transformation have always been fundamental to its creation. As cultures formed, political and social hierarchies threatened by music’s uncontrollable powers managed those subversive tendencies by co-opting them, only to be met by some new musical innovation from the underclasses.

Beethoven is part of this large-scale history, but that is easily obscured by casual encounters with his work. A sonata played amidst the works of others, a concert featuring Symphony No. 9 — these reinforce the notion of classical music as an “austere memorial” that must be venerated. What the 250th anniversary promises is a steady, consistent experience of his music, with enough exposure to clear away the dust of received wisdom about classical music and reveal how essential Beethoven is to humanity.

Classical music has become the illusion of an idealized world of form and art, notes coming together into a temporary symmetry and architecture; poetry and music combining for an imagined and idealized life of the mind and the heart; the frequently ridiculous assertions of opera which even the dedicated opera lover must accept to enjoy the art.

Beethoven is outside of all that. He combines the personal expression and formal means that place him at the pinnacle of his art.

Pianists play his sonatas because they are central to the repertoire; composers, theorists, and musicologists study them because they are the foundation of modern harmony; listeners crave them because they are thrilling and beautiful. To contemporary audiences — weaned on pop music and movie and TV melodramas — Beethoven sounds like the composer’s deepest thoughts and feelings streaming off the page.

He is the most human figure in classical music, and perhaps in all music. Beethoven is the only classical music figure this writer has both studied in the conservatory and talked about over beers with strangers in dive bars.

Human tendencies

One such stranger remarked to me that Beethoven is “the sound of the soul.” This seems easier to hear for those with only casual experience, or none, of classical music — people unburdened by debates over genius and mastery that can get in the way of what’s at the heart of his music, which is effort.

Effort is basic to the human experience, as is the hope, which Beethoven realizes, that it will lead to some kind of transformation or transcendence. His music captures imaginations far outside classical music because it speaks so directly to our everyday experience.

One need know nothing of the Heiligenstadt Testament (a letter Beethoven wrote, meant to be read after his death, in which he describes thoughts of suicide over his advancing deafness before finding the determination to persevere and overcome), to feel this in the gut: that Beethoven made music to assert his existence in the universe, not philosophically but physically — the deaf composer forcing existence to hear him.

He was the first existential artist, and he was also the first modern artist, making music for the public and creating the idea of the artist as a separate social class. He had aristocratic patrons, but he did what he wanted. That also made him the first avant-garde artist, declaring his independence from acceptable notions of music making. Like other great avant-gardists — Wassily Kandinsky, Martha Graham, Charlie Parker — his work is always fresh because it was made to open up new pathways, and so risked failure. There is little in classical music, even since WWII, that sounds as daring as the “Eroica” symphony — nor as willing as to set up something familiar before destroying it, nor as wild.

Wildness is an integral quality in Beethoven, in his hands it ranges from the velocity (not necessarily speed but forward motion) of the coach reaching the countryside in the first movement of the “Pastoral” Symphony No. 6, to the frenzied movements of the “Appassionata” Sonata and Symphony No. 7, to the late music that glides along the tightrope between organic form and chaos: the Op. 111 Piano Sonata in C minor, the String Quartets, Op. 127 through Op. 135, from 1825-1826, and especially the bulk of the Symphony No. 9.

Starting over

The specific character of the late music is Beethoven’s final triumph over his deafness. By losing his hearing he found his deepest freedom as a musician. No longer concerned with how the notes might sound together, he could follow his mind wherever it might go and put that on the page. And so the Arietta – Adagio molto movement of Op. 111 sounds like an extraordinary meditation, starting with a prosaic, naive feeling and ending up in an exalted, mystical place. The Op. 131 String Quartet in C-sharp minor impresses one as an extended daydream.

Then there is Symphony No. 9 — a benchmark so solid that compact discs were designed around it, with enough data storage to accommodate a complete performance of Beethoven’s Ninth. Famous of course for the “Ode to Joy” and its message of brotherhood, one is always struck by how the music appears out of nothing, like subatomic particles bubbling out of the foam of spacetime, and also how it is always on the verge of exploding into fragments.

The music is willful; though fixed on the page it still runs away from the musicians and the listener, daring them to keep up. That’s the experience through the first three movements, and when the chorus enters after the Turkish March and fugue in the final movement the words are a greeting — we have arrived at the place the music prepared for us.

Beethoven is always beautiful and exciting in turn, and the excitement of pieces like the Ninth Symphony is not just abstract or intellectual, it is a physical thrill. Hearing Beethoven played to the last degree is as exciting as anything in music — a great rock guitar solo, hearing a favorite dance song coming on at the club, a stadium full of people singing “Rebel Rebel.” Beethoven is always beautiful and exciting because he’s not about the pleasures of the parlor or the aristocracy; he’s not trying to convince you about the nobility of an opera character; he doesn’t just want you to waltz (though he does). He’s beautiful and exciting because his music is about the life-affirming freedom to think and feel.

Beethoven is not genteel; he’s not a part of the culture of classical music, of institutions, of academic composers and musicologists that claims him. His agenda is universal: being human, and being one’s self. Hearing his music once in a while may be a spark, but immersive exposure turns this into a credo, a way of being in the world.

This is something that music in general aspires to, and that classical music institutions are always trying to convince us resides in their programming. The problem faced by orchestras and the like is that, as classical music became “classical,” it gradually lost the point of what Beethoven did, which was not to make art that we should admire from a distance, before moving on to the next example — a set of abstract forms to be judged on how one note follows the next — but that music is the stuff of life. It’s made together, by and for each other. It’s made out of a history of beatings at the hands of his drunken father, out of illness, loneliness, personal pride and dignity. It’s a diamond squeezed out of the pressures of life. Popular music dominates the public sphere because it is about just those things.

Beethoven is those things, too, meaning and reality, and that’s why, even though he may not be that popular with the aficionados, he speaks to everyone. The more one hears Beethoven, the clearer and stronger this becomes. More Beethoven might make classical music as popular and meaningful to society at large as the insiders seek. Too much can never be enough.

Carnegie Hall’s Beethoven Celebration begins 7 p.m. Thursday, January 30, when Anne-Sophie Mutter and Friends play the “Spring” and “Kreutzer” Sonatas and the “Ghost” Trio. carnegiehall.org; 212-247-7800.

Posted Jan 30, 2020 at 8:23 am by nimitta

A lovely and inspiring essay, George!

Every single Beethoven performance I’ve heard lately has pulsed with that sense of freshness, as well as LvB’s almost inconceivable boldness and formal genius – even in works I’ve played or heard countless times.

Pondering the imminent 250th last year, with all its “anniversary-driven programming”, I too felt a twinge akin to Alex Ross’s disdain, but not for long. All it took was returning to the music’s presence, vibrating with its soulful energies and flowing along with its wildly original narratives. Beethoven’s heartfulness is right there on the page, somehow, whether evoking keen humor, erotic longing, fiery anger, or spiritual transcendence.

One last observation: to my ears, Beethoven attained to the farthest frontiers of innovation and transcendence not in his orchestral scores but in solo and more compact chamber works – certainly nothing approaching the far-flung explorations of the Hammerklavier or Große Fuge. When I hear/read them today, they still sound as if dropped down from outer space, and seem to lie somehow out ahead even of our time.