DiDonato, Nézet-Séguin team up for a chilling “Winterreise” at Carnegie Hall

A work like Winterreise is so familiar, it can be difficult to approach without preconceptions. That’s not to say it gets stale: a piece so deep and so complex will always have something to offer a listener. Yet most performances of Schubert’s crowning work are given by lieder specialists who have traveled the world singing these twenty-four songs over and over, studying and exploring every bar until they’ve achieved a kind of expertise.

Joyce DiDonato is a relative newcomer to Winterreise. She first tackled the cycle with Yannick Nézet-Séguin in Kansas City almost exactly a year ago; since then she had performed the work only a handful of times before bringing it to Carnegie Hall on Sunday afternoon.

Far from feeling unsettled, her relative lack of familiarity made for a searching interpretation of the cycle, her emotions raw, her musical choices seemingly as spontaneous as though she were encountering the text for the first time.

Hardcore purists will object to DiDonato’s framing device: when she took the stage, an introductory surtitle announced “I received his journal in the post,” and she then mimed reading from said journal for the entirety of the cycle. We’re meant to understand that the singer here is the unknown beloved first referenced in “Gute Nacht.” The conceit may feel contrived on its face, but it seemed to feed her, generating the intense emotional responses that made her interpretation so moving.

From the very start of “Gute Nacht,” it was clear what would make this an extraordinary performance: not the color of DiDonato’s voice itself, though there’s always a certain thrill in the laser focus of her cool mezzo-soprano. Rather, what stood out was the heavy emotion that came through in her singing, as she lingered on a syllable here, pressed her tone there. She created vivid feelings with her contrasts, communicating a bleak emptiness in the nearly static opening of “Gefrorne Tränen,” and then allowing her emotions to thaw and grow into forceful declamation.

“Der Lindenbaum” was an ideal showcase for the astonishing control DiDonato has over her instrument, seemingly able to change the entire timbre of her voice at will. In “Irrlicht” we heard the divergence between the beaming clarity of her top voice and the burning warmth of her chest voice, quickly and flawlessly moving from one to the other, and back.

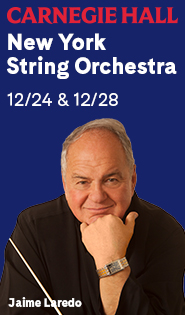

Nézet-Séguin, of course, is not primarily a pianist by trade. But as music director of the Metropolitan Opera, he knows something about working with singers, and proved an excellent partner to DiDonato on Sunday. He lacked the facility to enrich the music with a lot of subtle gestures, and some moving figures, such as the breezy opening to “Der Lindenbaum,” felt not entirely at ease. Still, there was something earnest in Nézet-Séguin’s straightforward treatment of the accompaniment, communicating the vivid images in Schubert’s writing without being overly precious.

Singer and pianist were both at their best in the last half-dozen songs of the cycle, creating in these a smaller journey with its own emotional range, building an uncomfortable tension until the haunting resolution. “Täuschung” paired a soft glow in the piano with the dreaming melody above, and “Mut” was sung with such firm confidence, it felt like a last cry of defiance against the gloomy destiny of the cycle. Nézet-Séguin approached the opening of “Die Nebensonnen” with all the reverence of a chorale while DiDonato took up the melody with breathtaking simplicity. A spellbinding reading of “Der Leiermann” began with a feeling of cold detachment, its morbid curiosity giving way to a sympathetic grief that reached its climax on the cycle’s gnawing, unanswered final question.

The finest example of the pair’s approach came in “Das Wirtshaus,” the twenty-first of the twenty-four songs in the cycle. Thematically, this is among the darkest texts in an overwhelmingly bleak work, the “Tavern” of the title being in fact a graveyard where the speaker hopes to find a “room” to rest. Yet in Schubert’s major-key setting, we hear no apparent desperation, but hazy bliss and complete calm. Here, the shining purity of DiDonato’s singing and the warm mist of Nézet-Séguin’s accompaniment underscored the contradiction, leaving the listener shaken.

Within the song tradition, Winterreise is profound, a genre-defining work, but even beyond its own domain it stands as one of the great achievements in art. The poetry and music breathe through each other, so intertwined it’s impossible to imagine one without the other. When great artists undertake Winterreise it is a transporting experience, and we’re lucky that DiDonato has added her interpretation to the performance tradition.

Posted Dec 17, 2019 at 6:53 pm by Schubertiade

Seriously?

Mr. Nezet-Seguin should be honest enough to recognize that playing the notes is not enough. There are plenty of extraordinary collaborative pianists out there to do the job. Do not steal the work.

ON the other hand, there is no depth in that interpretation. Everything is conceived with the same approach, a boring and light head voice that does not take us to the dark mental labyrinth that Schubert carefully built.