Mostly Mozart offers a brilliant silent-film “Magic Flute”

The classical music world often confuses maintaining the life and relevance of the art form with preserving it behind a hermetic case, untouched by either the present or the audience, like an ancient vase. This is most pernicious in opera, where works from specific historical periods are too often staged as if they were being performed in the past.

Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, being about philosophy and magic, is more flexible in this regard than most—the bedrock upon which Julia Taymor’s exceptional fantasy and puppetry production for the Metropolitan Opera stands. That staging is one of the great contemporary opera productions.

One can now add the Komische Oper Berlin staging by Barrie Kosky, which made its New York debut Wednesday night in the David H. Koch Theater, under the umbrella of this summer’s Mostly Mozart Festival. The performance confirmed this production’s brilliance and how it makes Magic Flute one of the most purely entertaining opera experiences one can have.

This Zauberflöte is a masterpiece of conception and execution. The staging turns the opera into a movie, one that has live performers within it. That alone, the rare integration of the dominant art form of the 19th century with that of the 20th, is worth the price of admission. But the execution is masterful, intellectually thrilling and tremendous fun.

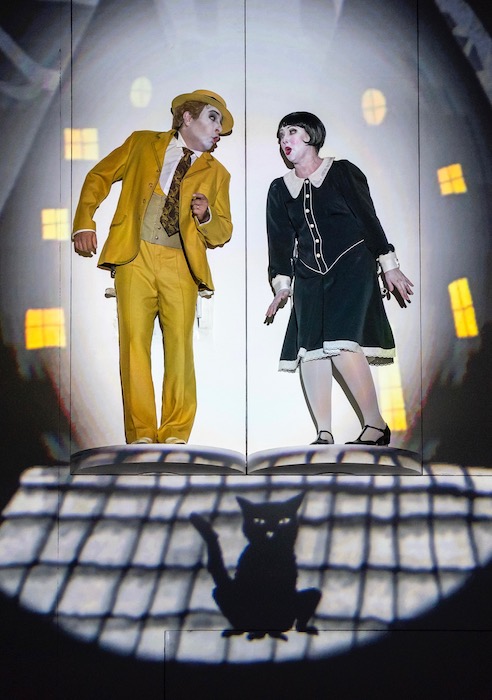

The staging—by the British theater company 1927, made up of director Suzanne Andrade and animator Paul Barritt—makes the opera into an animated film, projected onto, around, and over the performers—it provides setting, action, narration, and even characterization. The visual style is a mix of classic silent film era works and stars: Tamino (tenor Julien Behr) and Papageno (baritone Rodin Pogossov) are two sides of the Buster Keaton coin; soprano Maureen McKay is done up as Louise Brooks, tenor Johannes Dunz’s Monostatos is Max Schrek’s Nosferatu, and the Three Ladies (Ashley Milanese, Karolina Gumos, Ezgi Kutlu) are Weimar vamps. Bass Dimity Ivashchenko was costumed by designer Esther Bialas as a throwback, good formal burgher. (The opening night cast was one of two that will alternate across the performances.)

This was beautiful to see, and done in the spirit of animation, full of visual humor. The concept goes so far as to do away with the dialogue and replace it with title card-like text, projected to the accompaniment of Frank Schulte playing bits of Mozart’s K. 397 and K. 475 Fantasias on a fortepiano. This seals the performance’s universe into an infinite spiral, turning the dialogue into both Mozartian recitatives and silent movie live piano music.

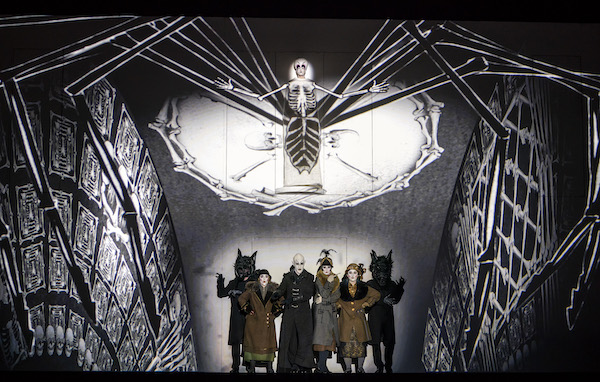

Everything is the story, everything is the opera. Die Zauberflöte is already an ensemble piece with proportionally little in the way of bravura sections. The obvious ones are the Queen of the Night’s (soprano Audrey Luna, replacing an ill Christina Poulitsi), Tamino’s Act I “Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd schön” and Pamina’s Act II aria “Ach, ich fühl’s, es ist verschwunden.” One is spoiled by Kathryn Lewek’s incredible Queen of the Night at the Met, but Luna’s brighter, lighter voice had the agility for the part and her inherent sweetness was a strong contrast with the depiction of the Queen as a giant spider monster.

Behr has a slightly more virile sound that one hears in Tamino; his prince was a young man, with a nice touch of maturity that fits well into the staging. His “Dies Bildnis” was lovely, and McKay’s “Ach, Ich fühl’s” was marvelous, the one moment in the performance where the singing surpassed the overall effect of the staging and exclusively captured the attention.

In every other regard, this was a seamless integration of performers with presentation, and cast and musicians into the score. Pogossov had an easy manner as Papageno, and Behr’s Tamino moved and stood with just a touch of Keaton-ish melancholy and longing.

Louis Langrée, conducting the Mostly Mozart Festival orchestra, was tackling the score for the first time, but it could have been the 100th—his tempo modulations were detailed and impressive, the orchestra’s playing was lively and polished, with a rhythmic bounce, and the balances between instruments and voices were excellent. This was key, as this was a lighter-voiced cast that one commonly hears, which is not only fine for Mozart but a real part of this score, as it was originally created with a broad range of vocal talent.

There is so much magic and philosophy in this Zauberflöte—the magic flute itself is a winged, animated character, and Papageno’s bells are tiny, shrouded dancing dolls. Monostatos’ slaves are werewolves, and the three boys (members of the Tölzer Boys Choir) are made, by the film, into exotic moths.

Sarastro is at times represented by a giant mechanical head, the brain composed of gears and words like “Arbeit” (work) and “Kunst” (art).

And there is slapstick—Papageno lights a bomb when he considers ending his life, and it goes off with a mighty crash from the orchestra—and wit: the Three Ladies are, in the production, named Klatsch, Tratsch, and Schwatz, essentially different versions of gossip and idle chatter.

At the heart of this production is a complete disregard for 150 years of conventional thinking and accumulated, arbitrary tradition. Kosky and 1927 have gone back to the basics,—Mozart’s and Schikaneder’s desire to entertain, offer some affirming wisdom, and sell tickets. This Zauberflöte offers a wonderful helping of the first two, and by all rights should sell mighty amounts of the last.

Die Zauberflöte continues through Saturday, July 20. The second cast performs Thursday and Saturday. lincolncenter.org

Posted Aug 01, 2019 at 11:14 am by Christopher Kelly

Best performance of this opera I’ve seen.