Chamber Music Society evokes the otherworldly mystery of George Crumb

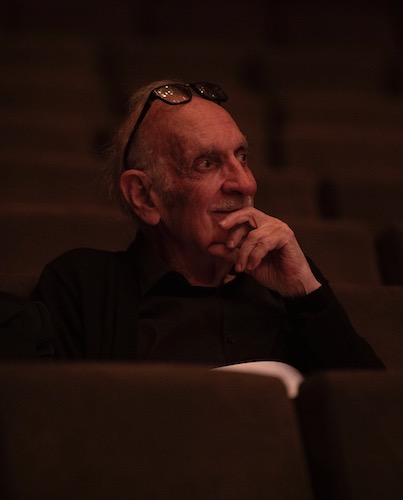

George Crumb. Photo: Tristan Cook

George Crumb will turn 90 in October, and this week the American composer has been getting an early birthday party, thrown by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. The second concert in this series of two came Tuesday night, and both the composer—who was sitting in a box stage-left—and the audience enjoyed an exceptional treat.

The concert opened with his 21st-century The Ghosts of Alhambra, while the bulk of the program offered two of his greatest masterpieces: Black Angels and Music for a Summer Evening (Makrokosmos III). Both of the latter were composed in the early ’70s, and Tuesday all the music fit into the mysterious web of Crumb’s aesthetic, with its uncanny effect on the listener.

That aesthetic mixes ideas about order, symmetry, and proportion from the Renaissance and pre-modern thinking with sensations of mysticism, fear, and wonder that prehistoric man felt when regarding the dark depths of the night sky. Part astronomer and part alchemist, Crumb’s music, more than that of most every other composer, creates its own universe, one that sees science and magic as intimate companions. His use of amplification, his remarkable scoring, and, most of all his ringing, sustained, resonant sounds carve out an experiential space that has one wondering if his sounds come from the past or from the future.

This was established by the opening songs. The Ghosts of Alhambra is book one of his series Spanish Songbooks, all settings of Lorca. This first book uses an instrumentation different from the following ones—baritone, guitar, and percussion.

The performance from soloist Randall Scarlata, guitarist Oren Fader, and percussionist Daniel Druckman, was exemplary. The colors were variegated and the textures delicate. Crumb’s writing in this book is familiar from his famous Lorca setting, Ancient Voices of Children; the instrumental accompaniment is spare, exceedingly precise, setting patterns that sit below the voice. The baritone has some lines that he sings, but most of the time uses intoned speech—his part sits between song and recitation.

In the right hands, this is more expressive than more stylized art song forms, with a greater possible range of meaning to explore. Crumb’s writing is masterful, and Scarlata, was spot-on. There is a small school of critical thought that believes Crumb is kitschy, full of filigree and bent notes; but to paraphrase, there’s no kitsch in Crumb, only kitschy performers. And Scarlata had the right touch, committed, un-showy, serious about the words but relaxed in his manner.

Before intermission, violinists Sean Lee and Kristin Lee, violist Richard O’Neill, and cellist Minai Marica played Crumb’s sole string quartet, Black Angels. Written during, and in clear reaction to, the Vietnam War, there was a time when it seemed the piece might become a relic of its era, like Bernstein’s Mass. But the country has been at war again for nearly twenty years, and the subject of “The Night of the Electric Insects,” which before were so clearly helicopters, now are unmistakably drones.

Black Angels, despite its intense, aggressive moments and things that still make audiences chuckle nervously, like the musicians’ shouts, has a gripping appeal that cuts through genres. Part of that is the amplification, which brings the deepest and quietest moments into direct contact with the listener, another part is the stunning, rapturous beauty of passages like “Pavana Lachrymae,” where the music is a fragment from Schubert’s Death and the Maiden, played in gamba style. And then there are the pure sounds and how fascinating they are, the shouts, the glass harmonicas.

The quartet of Chamber Music players delivered a great performance. They had Crumb’s pace and progression, which is based around theatrical, more than musical, ideas. The symmetrical form, the clear delineation of sections, the use of voices, the musicians laying down their main instruments to pick up others, made for an imagined, hermetic liturgy, not least of which is the “God-music,” which Marica and the group played with a weighted deliberateness. These thoughts on the details are of far lesser importance than the experience, which was transporting and mind-cleansing.

That held also with Music for a Summer Evening, which came after intermission. Pianist Gilbert Kalish, who has been playing Crumb for more than forty years, led a quartet of pianist Gloria Chien and percussionists Ayana Kataoka and Ian David Rosenbaum. Built literally on the past, with a fragment from Bach and structural techniques that go back to Medieval music, the music comes out to the listener with dazzling colors—strummed and plucked piano strings, pitched metallic and wooden percussion, a large-scale, shimmering soundscape made with the sustain pedal on the pianos, augmented by the tam-tam.

Music for a Summer Evening is in a state of constant vibration; there’s always a wave of sound propagating—the evening surrounds the audience. Like Black Angels, the piece is a kind of abstract narrative, there’s a sense of transformation through time and experience, although it may only be happening in dreams.

This was another expert performance. Technically, balances were ideal, but the main thing again was the pace, the sense of otherworldly calm, that time was no longer being marked and so the musicians could ensure that the music unfolded with perfect clarity and an unshakeable grip on the audience. The final section, “Music of the Starry Night,” sounded like that last darkness before dawn broke, and it was then that one could exhale all the music that had come before. The regret was that one then had to return to the real world.

The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center presents music by Mozart, Rota, and Dohnányi, 6:30 and 9 p.m. April 25. chambermusicsociety.org