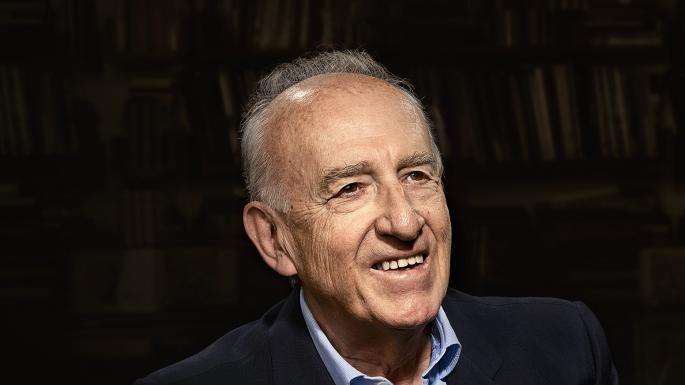

A lion in winter, Pollini still offers spellbinding moments

Maurizio Pollini performed at Carnegie Hall on Sunday.

With an elder statesman of the piano like Maurizio Pollini, recitals can be difficult: often they become less a complete show of musical and technical ability than an exploration of where the artist’s faculties have slipped and where they haven’t.

So it was in Pollini’s recital at Carnegie Hall on Sunday afternoon, where he found a handful of gems in a challenging program that offered both frustrations and rewards.

He began with Brahms’s three Opus 117 intermezzi, and even these relatively simple works were a mixed bag. No. 1 proved maddening, as he consistently rushed through the pickups to each phrase, rolling right through the lingering silences that are so crucial to the music’s hypnotic calm. No. 3 stated with soupy passagework, though Pollini found balance later on, allowing the melody to drive forward. The most successful of the three was No. 2, where he felt more comfortable in the natural cadence of the arpeggios.

The most substantial piece of the afternoon was Robert Schumann’s Piano Sonata No. 3, the “Concerto without Orchestra,” in a performance that was rewarding, albeit again with technical shortcomings. Pollini got off to a rough start as the opening salvo was too messy to land with much force, and the rhythmic figures thereafter lacked precision. His reading of the Allegro brillante in general felt contained, as though treading carefully; as a result he lacked the energy to capture the music’s heroic side, even while he found exquisite moments of intimacy.

The rest of the sonata was more compelling: Pollini’s statement of the Andantino theme was just right, somber but not without energy, and he brought a range of expression to the variations thereafter, exploring a series of distinct perspectives on the same idea. In the finale, he showed surprising clarity, bringing out the melody as a way of compensating for a lack of dexterity in his passagework.

Pollini has always been thought of as a Chopin guru first and foremost, and in his golden years he hasn’t shied away from that reputation: the entirety of the second half was a Chopin set, leading off with the two Op. 62 Nocturnes. Both were thoughtfully played, but the first was the real stunner between them. Pollini approached the music with an apparent simplicity that belied its depth, allowing the unassuming melody to speak with its own expressive weight.

His playing was stiff in the both the Polonaise in F-sharp Minor, Op. 44 and the following Mazurka in C Minor, Op. 56, No. 3; yet he more than made up for them with the Berceuse in D-flat, Op. 57, by far the highlight of the afternoon. With a gentle, rocking breeze in the left hand and a dreaming melody on top, Pollini’s rendition was spellbinding, exquisitely placing each phrase and finally finding enough comfort in his fingers to reel off the scales in glowing cascades.

The closing Scherzo No. 3 in C-sharp Minor, Op. 39, could have been an energetic end the program, but felt out of place, and his fingers got tangled again in two encores, the Ballade No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 23, and especially the “Winter Wind” Etude, Op. 25, No. 11. Yet these three were all an afterthought: the lasting impression of the afternoon was that sublime Berceuse, a prime example of what Pollini at his best can still offer audiences.