Saariaho’s compelling music transcends Sellars’ uneven contributions in “Only the Sound Remains”

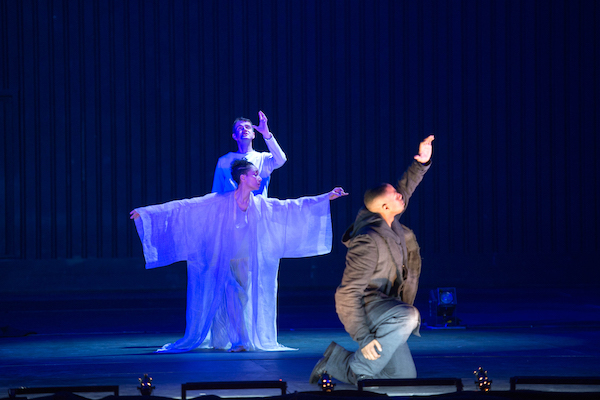

Davone Tines (front), Nora Kimball-Mentzos and Philippe Jaroussky in “Only the Sound Remains” at White Light Festival. Photo: Ruth Walz

The first question to ask of any opera throughout the genre’s history is “Why are these people singing?” If there’s no good answer, they probably shouldn’t be.

This answer is harder to come by when the opera’s subject comes as a successful story from another medium; plays, novels, movies. In that case, the opera needs to do something better than, or at least constructively different from, the original, and must do it via music.

And so it was with the U.S. premiere of Only the Sound Remains, a collaboration between composer Kaija Saariaho and librettist and director Peter Sellars, which played at the Rose Theater Saturday night as part of Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival.

Only the Sound Remains is made up of two one act dramas, “Always Strong” and “Feather Mantle,” each adapted from Ezra Pound’s and Ernest Fenollosa’s translation of a pair of Japanese Noh plays, Tsunemasa and Hagoromo. Coming from traditional sources that already integrate music into their drama , it was often unclear why any part of these should be sung.

Noh plays mix the material and the supernatural. The stories in Only The Sound Remains were, respectively, about a priest praying for the soul of a dead soldier, and a fisherman taking the feather robe of a moon spirit (a “Tennin”). For each part, bass-baritone Davóne Tines sang the human character while countertenor Philippe Jaroussky sang the supernatural one (and in “Feather Mantle,” Nora Kimball-Mentzos also danced the Tennin).

Saariaho’s style of palpable atmospheres of sound, textures, colors, and moody beauty, was an ideal fit for the subject matter, at least as far as the instruments were concerned. Her score, conducted with precision and careful attention to dynamics by Ernest Martínez Izquierdo, was played by the vocal quartet Theatre of Voices, The Meta4 string quartet, and musicians playing the flute, percussion, and the traditional zither-like Finnish instrument, the kantele.

The split between the two voices—that of a man and the other an ethereal one—was an obvious decision that was fully realized by the singers. Tines sang with a rounded, masculine sound, sleek, strong and cutting, Jaroussky had a slightly piping quality that carried through the orchestration, with a soft edge. He was equally fine conveying warmth and malevolence. Both singers were miked, but that was not for reinforcement. Rather, Saariaho’s score extended the instrumental and vocal qualities with sound processing—realized in an excellent sound design that surrounded the audience—and the miking was the means to mix everything together.

The music, as something to listen to, was fine throughout, but as musical drama it was drastically uneven. In “Always Strong,” the source of the problem seemed to be the libretto. Sellars’ awkward writing comes off consistently as made with an ear for dialogue in the music dramas, yet not for singing.

The difference may be subtle but it is crucial. If the vocal lines—their rhythms and phrases, their expressive means—would be more meaningful and dramatic when spoken, then it shouldn’t be an opera.

Noh plays manage the suspension of disbelief that ghost stories demand via strict, ritualistic structure—masks and stylized movements present the performers as something other than normal flesh and blood.

Sellars’ direction in “Always Strong” took the opposite approach, which was to humanize both priest and ghost, primarily though an erotic encounter that may or may not have been a dream. Like many Sellars efforts, it came off as simplistic and misguided—along with the libretto, that decision to mix the supernatural with the physical worked against the ethereal quality of Saariaho’s writing.

“Feather Mantle,” on the other hand, was quite successful, the music even better than the first play and—even though the libretto was still often rough—that turned the original play into a successful opera. The subject matter alone seemed vastly more fruitful to work with than the hermetic, ritualistic, and culturally specific Tsunemasa. There was a sharp contrast between body—the fisherman—and the spirits of the Tennin.

Saariaho supported the dancing with more rhythmic energy than one is used to hearing in her music, and it was compelling. The juxtapositions between the real and the supernatural were starker and more evocative, and even Sellars’ direction worked—the fisherman, supported by James F. Ingalls’ superb lighting design, continually chased the elusive spirit world, until he was left in a kind of mad fugue state, both beautiful and menacing.

Only the Sound Remains will be repeated 5 p.m. Sunday. whitelightfestival.org