Nono’s “Intolleranza 1960” finds contemporary resonance from Botstein, ASO

Luigi Nono’s “Intolleranza 1960” was conducted by Leon Botstein with the American Symphony Orchestra Thursday night at Carnegie Hall.

Leon Botstein, music director of the American Symphony Orchestra, knows the contents of classical music’s attic better than just about any conductor working today, and it’s guaranteed that every year ASO will dust off works that no one has seen in performance for decades.

Some of these lost treasures have not fared well in their comebacks, either because they weren’t so great to begin with or they needed a conductor who can exert greater control over large forces. But the man and the material made for a creditable pairing Thursday at Carnegie Hall in the finale of a season that took “Music and Politics” as its theme.

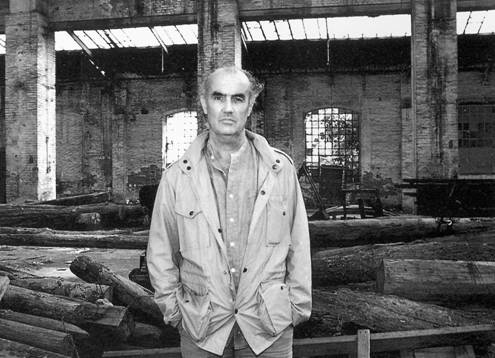

An atonal communist opera from postwar Italy, Intolleranza 1960 is exactly the kind of oddity that makes ASO consistently intriguing. The composer, Luigi Nono, was so committed to music as an engine of social justice he joined the Italian Communist Party, and so devoted to avant-garde method he married the daughter of twelve-tone pioneer Arnold Schoenberg. Botstein, in his customary pre-show talk, said the musical vocabulary represented by Nono has “drifted into disrepute,” although it’s fairer to say it’s been selectively absorbed into classical’s collective aesthetic.

Thursday’s performance did without the complicated staging of a 1961 premiere that enraged many Italians and cemented Nono’s reputation as confrontational. The operatic soloists stood in traditional evening wear at the front of the Perelman Stage, and it fell to concertgoers to supply action and scenery for themselves as they followed along to English translations in the program notes. The opera also ran a trim 65 minutes — a relief, considering the notes had the audience committing itself to nearly two hours of anti-melodic revolutionary fervor.

The tale of a bone-weary migrant laborer beset by xenophobic hatred and violence opened with a spoken dedication — in English — to “those who love life.” The resounding first statement, from the 50-member Bard Festival Chorale, was the dedication’s dark opposite — a dread-inducing, Dantean swarm of voices that called to mind György Ligeti’s Requiem (although Nono wrote his piece some years earlier). The lyric, as translated from Italian, championed love and humble self-sacrifice against adversity, but in the harsh, narrow harmonic intervals employed by Nono, the message received might as well have been, “Abandon hope.”

The Bard singers, under the direction of James Bagwell, were a highlight of Intolleranza 1960 and an authoritative presence throughout, projecting Nono’s fractured, eerie voicings and wailing walls of sound with confidence from their station behind the orchestra. More than the instrumentalists and most of the vocal soloists, or the conductor, Bagwell’s choir gave this allegorical beast much of its galvanizing force.

Among the soloists, the standout was Daniel Weeks as the Emigrant whose journey home is strewn with torments. He is heckled by nativists, including his former lover (Hai-Ting Chinn), attacked by police, tortured in a concentration camp, battered by propaganda from the state and mass media, and, finally, on the cusp of his return, drowned in a mighty flood that carries away the just and unjust alike. (This is still Italian opera.) In a performance that called for very little gestural acting, Weeks was the most convincing inhabitant of Nono’s dystopia. He communicated the Emigrant’s hope and despair with a laser-like tenor that pierced the instrumental clamor and gave emotional heft to arresting lines like “My life hangs/from the hook of necessity.”

Bass-baritone Carsten Wittmoser as a Torture Victim and baritone Matthew Worth as an Algerian were, if anything, underutilized as Weeks’ counterparts. The soprano Serena Benedetti appeared late in the opera as a faithful, solace-giving Companion to the Emigrant, but made her short time on stage fully count. Her shrieking aria professed hope — “I’ve felt the bliss of existence/even when the sky/was a mass of lead” — but in jarring intervals that the brain is conditioned to hear as horror.

Chinn, the mezzo-soprano playing the Woman scorned, seemed less at ease in Nono’s polyphonic siege, and struggled to assert her voice or character through the din. But some of that shortcoming fell to Botstein, who could have cleared her a path but chose to let the instruments, in particular brass and percussion, monopolize the acoustic space. Strings were barely audible throughout, except in isolation.

But the emphasis on percussion was also a strength of Nono’s writing here. Cascading drum and snare rolls evoked the martial fearsomeness of the garrison state, and there was a deft underlining of voices with touches of vibraphone. The whole orchestra functioned effectively as a kind of shadow force, echoing melodies as ghostly, fading trails.

Botstein managed for the most part to keep this whole angular construct rumbling forward. The most awkward sections, as it turned out, tended to be unsung — spoken or pre-recorded English-language verbiage representing bureaucrats, blaring headlines, sadistic cops and cameos by literary figures such as Jean-Paul Sartre. It was when this ostensibly edgy multimedia pastiche was shut off that Intolleranza tended to regain its composure.

The overall sensation of listening to this relic was like walking through an exhibition of cubist furniture. But even so there were striking finds — passages of twisted beauty and audacious contrasts of volume, pitch and rhythm, capably handled by Botstein. Nono emerged from this performance as a composer of great imagination, and more of a humanist and observer than a creature of pure ideology. Botstein was correct in saying the themes Nono explored (creeping authoritarianism, loathing and exploitation of immigrants) are relevant today — even if his modernist aesthetic never caught on as hoped — as a spur to activism and an antidote to the amorality of formal artistic beauty.