A composer plays herself in Glass-inspired concerto for human at ACO program

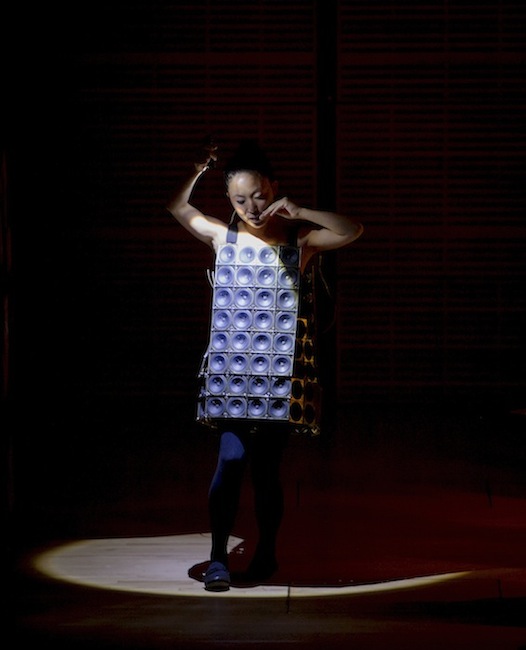

Composer Paucai Sasaki performs “GAMA XVI” in her speaker dress at the American Composers Orchestra concert Friday night at Zankel Hall. Photo: Jennifer Taylor

There were a lot of things going on at the American Composers Orchestra’s Friday night concert in Zankel Hall—different stories and different musical ideas coming together to celebrate—well, many things.

The concert was part of the ACO’s 40th anniversary celebrations this season, it was yet another birthday celebration for Philip Glass, now in his 81st year (his 80th birthday was January 31), and it was the first Carnegie Hall event in Glass’ position as this season’s Debs Composer-in-Residence. The title was “Reflected in Glass: Philip Glass and the Next Generation.”

And on top of that, there was a world premiere and a New York premiere, which almost made the opportunity to hear the third piece, Glass’s Violin Concerto No. 2, “The American Four Seasons,” seem the most humdrum part of the evening. Nothing could have been further from the truth.

The world premiere was of Pauchi Sasaki’s GAMA XVI, which was, as ACO artistic director Derek Bermel said in the introduction, a reflection on Glass. With Sasaki, this was both figurative and literal—a young composer, she is in the enviable position of being Glass’s protégé in Rolex’s Mentor and Protégé Arts Initiative. Amid the work is a quasi-reflection of the older composer’s taste and values.

The literal part had to do with Sasaki’s unique, pioneering instrument, the “speaker dress.” She has made it out of 100 small speakers, all shiny and reflecting light. It produced and amplified electronic sounds, which Sasaki generated with her voice and with physical gestures.

With this, the speaker dress transformed her into an instrument. This idea, and most of all her brilliant execution of it, was remarkable in performance. On top of a bed of long tones and some chords cribbed from Glassworks, played by an ACO reduced to a chamber sized string orchestra, Sasaki did the simple human things of speaking and moving.

This was touch-and-go at the beginning, mainly because of what seemed to be technical problems that hampered and distorted the amplification of her vocalizations as she slowly descended the stairs from the back of the hall.

Once onstage, the full effect of what she was doing was fascinating and mind-boggling. Moving her arms and hands as if she were playing an invisible theremin, she produced a sound that mixed together a quick whoosh with a dry timbre, like softly crunching leaves.

The technology created an organic feeling, even juxtaposed with acoustic instruments. Sasaki was playing herself, a striking experience.

GAMA XVI was more than just a novelty. This concerto for human had the unobtrusively fascinating sound of the finest ambient music. But then it turned, oddly, into something else entirely. Sasaki left the stage and was replaced by violinist Tim Fain, who played what was indeed a mini-concerto, full of Glassian repetition.

This was not bad, but it was so unexpected that by the time one got used to the “and now for something completely different” quality, the piece was over. It was intriguing, but needed more Sasaki.

The middle piece on the program had nothing whatsoever to do with Glass, other than being from the “Next Generation.” And it came from something of a representative of that generation, Bryce Dessner.

Dessner is best known as a guitarist in the critically esteemed rock band The National, and from his leadership of the neo-folk instrumental band Clogs. For several years now, he has also been carving out a career as a composer.

The ACO brought his Réponse Lutoslawski to New York for the first time. In this string orchestra work, Dessner responded to his study of the score for Lutoslawski’s hauntingly beautiful Musique funèbre.

Lutoslawski was one of the greatest composers of the 20th century, pioneering the seemingly impossible reconciliation between aleatoric procedures and traditional classical form and structure, all with the intelligence and elegance that was so much a part of the man.

Yet in its five movements, Dessner’s Réponse teased at being an homage without demonstrating any appreciation for the Polish composer’s work in general and Musique funèbre in particular.

Dessner lacks a competent handle on the basic craft of manipulating and structuring musical materials. While Réponse is an advance on his previous work in that it has traded in unvaried monophonic repetition for polyphony, it still did nothing more than state material, repeat it, then state some other material, the endless two and four bar phrases punishingly dull. The ACO, even with conductor George Manahan managing all the details, seemed unsure what to make of it all.

Yet the privilege of Dessner’s fame has earned him commissions from the likes of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and the Ensemble Intercontemporain, ballets and film scores, and collaborations with musicians like Jennifer Koh. He has opportunities that composers with skill, imagination, and ideas about beauty and meaning are begging for. Like the man said, life is unfair.

Tim Fain performed Philip Glass’s Violin Concerto No. 2 “The American Four Seasons” Friday night. Photo: Jennifer Taylor

After intermission Tim Fain returned to play Glass’ second concerto, and mostly wiped away the bad feeling. The composer’s Violin Concerto No. 1 was a landmark work, the second is its equal, while very different in style—it doesn’t sound like the Four Seasons, but it does vary solo cadenzas with ensemble/soloist movements in a way that is something of a cousin to the baroque concerto.

Glass’s writing for the solo part has a freedom found infrequently in his catalogue. The solo part also has an explicit romantic expression, so different than the emotions that most of Glass’ music keeps just under the surface.

With a big, beautiful sound—both sweet and somber—that was set in relief by the smaller sized orchestra, Fain played it like it was indeed one of the great romantic era concertos. He is a frequent Glass collaborator and has the technique to handle the music’s considerable challenges. What imprinted itself on the memory, though, was his great lyricism, the exciting weight of expression, and the human ebb and flow of emotions.

The American Composers Orchestra accompanies Gregory Spears’ Fellow Travelers at the Prototype Festival, January 12–14. prototypefestival.org. The Philip Glass Ensemble plays Music With Changing Parts 8 p.m. February 16. carnegiehall.org