Pierre Boulez illuminated in time and space at the Park Avenue Armory

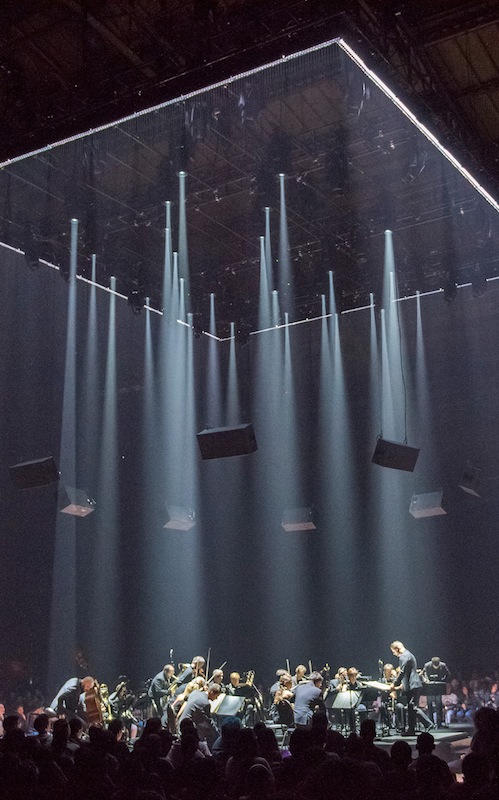

Matthias Pintscher conducted Ensemble Intercontemporain in Pierre Boulez’s “Répons” Friday night at the Park Avenue Armory. Photo: Stephanie Berger

Entering the Wade Thompson Drill Hall at the Park Avenue Armory Friday night, the first thought was of De Stijl architect Theo van Doesburg, who thought that factories were the cathedrals of the modern era. As a factory, the Armory in its day was old-fashioned, manufacturing soldiers and military glory.

But as a cathedral Friday night, it was modern and wonderful. The Ensemble Intercontemporain, conducted by Matthias Pintscher, opened the first of two nights of performances of a single piece, Pierre Boulez’s Répons, and the event was a celebration of profound timelessness.

The performance was organized and lightly, but powerfully, staged by Armory artistic director Pierre Audi. Musically, this was the first correct realization in the U.S. in more than decade of what is arguably Boulez’s greatest artistic achievement.

Répons is spatial music, and the layout of musicians and audience is crucial. At the Armory, the piece is played twice, with the audience sitting opposite to where it was for the first performance. This writer sat behind the low brass in the first half and in front of the ensemble for the second.

In the Drill Hall, the audience surrounded the ensemble on the four sides of a square, and the six soloists surrounded the audience, as did a series of speakers, through which the processed sounds of the soloists are spun around the listeners. That is fundamental to the sound of the music—the soloists play percussive instruments, and their decay is frozen via signal processing and then passed through the speakers, which entirely alters the listener’s sensation of space and time.

The program credited Audi with “mise-en-space,” not just an evocative but an accurate way to describe his responsibilities. He reshaped the Drill Hall space with partitions and a platform stage, and lighting by Urs Schönebaum.

The stage was enclosed in a cube of soft, white light, articulated by a wisp of fog. This was an intuitively timeless setting most commonly experienced in a liturgical or meditative context, like a cathedral.

Boulez was raised in a strict Roman Catholic household, and his schooling was even more rigorous: 13-hour days at a seminary from the age of 6. By the time he was 18, he no longer professed the faith. But that experience leaves a deep impression, disciplines the mind and expands one’s worldview. It is easy to hear a liturgical focus on stillness, a repetition meant to uncover revelation, and stained-glass colors in Boulez’s work.

The illumination was also museum-like, turning the platform into a pedestal upon which an object is preserved. Museums take objects away form their contexts in time while seeking to protect them from inevitable decay. That in turn is a metaphor for the dullest kind of preservation of classical music—repeating the same pre-packaged favorites mainly because they are old, well-known, and in no way a challenge to the listener.

But in the Armory, the immediate, overall, and lasting effect was to turn the concert-going experience—show the ticket, sit down, enjoy the show, applaud, head home—into something entirely different with too many dimensionsto completely apprehend right away. The feeling was like a gentle hypnagogic jerk that doesn’t startle one awake but leaves one floating in an uncanny dream-state, unbound by physical limits. It was completely, wonderfully out of the ordinary.

The musical performance itself was as fine as one can imagination. The Ensemble Intercontemporain played with complete command of the score, not just slicing into the exact rhythms but expressively mindful of dynamics, pulse, the large-scale shape of the piece. Pintscher’s conducting was clear, relaxed, and for such complex music refreshingly minimal. He clearly had complete confidence in the ensemble and also seemed more than a bit enthralled by the soloists.

Those six musicians—pianists Dimitri Vassilakis and Hidéki Nagano, percussionists Samuel Favre and Gilles Durot, harpist Frédérique Cambreling, and cymbalist Françoise Rivalland—played with a sparkling energy. Each phrase opened with a noticeable explosion of forward motion, and even when the music was at its densest, each instrumental voice was clear and forceful. In the Drill Hall space, Rivalland’s cymbalum had a particularly rich and powerful sound.

If a musical performance can be honestly said to honor an artist or an idea, it was this. There was the exceptional realization of Boulez’s score, an expression of the sheer beauty and sensuality of the music; the demonstration of the composer’s thinking about acoustic sounds, signal processing, computer music, and how space affects and realizes unique psycho-acoustic experiences.

And that was all just the rich, marvelous surface of something that went far deeper. The cathedral was not just the metaphor that stimulated the imagination, but an edifice built out of light and sound. As a musical event, this was temporary and fleeting, but as an illuminating representation of Pierre Boulez, this left one with with a musical prayer of sorts, a contemplation on time, space, and sound.

The final performance of Répons is 8 p.m. Saturday. armoryonpark.org

Posted Nov 10, 2017 at 4:32 pm by Edith Alston

So sorry I missed this, will pay better attention to my Armory brochures.