Philadelphia Orchestra offers strong symphonies and a poignant appearance by a pianist

Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducted the Philadelphia Orchestra Tuesday night at Carnegie Hall.

There is a poignant agony to witnessing one’s idols fade and fail, more so when they represent ideals of individuality.

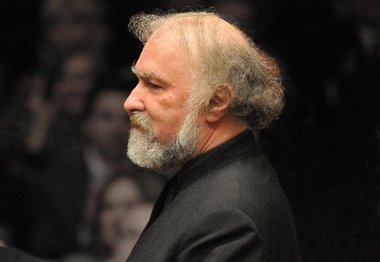

Pianist Radu Lupu is one of the great musicians of the latter half of the 20th century. His limited discography (he stopped recording twenty years ago) and concertizing have had him prized for his poetry, clarity, sense of spontaneity, and tightly focused fire. Each infrequent appearance, like Tuesday night’s concert at Carnegie Hall, is a notable event.

Radu Lupu

Lupu appeared with the Philadelphia Orchestra and conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin, playing the Mozart Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K. 491 in a strange performance that left one with the painful question of why Lupu was continuing his public performances.

The concerto was the unappetizing filling in an otherwise satisfying musical sandwich, with two symphonies—Bernstein’s “Jeremiah” and Schumann’s Second—as the bread.

Lupu’s performance was simply wrong, a jumble of bad and incoherent ideas from both the soloist and Nézet-Séguin. The only thing consistent was the lack of flow.

One culprit was the orchestra. The conductor’s take on Mozart was heavy and mannered. This concerto is some of the darkest music Mozart ever made, yet it’s still Mozart, and the stürm und drang is circumscribed via elegance and intellect. Wringing every last bit of bathos out of the piece dishonors the score.

The other culprit was Lupu, though at first his playing hinted at positive possibilities. His first entrance was as clear and unadorned as could be, it seemed laden with foresight and was a relief after the exaggerated orchestral playing. But as the piece developed and the solo part became more active, this all fell apart.

Lupu’s technique was simply not up to the demands. He dropped chunks of notes in 16th-note runs, and smeared other figurations, and his rhythms were frequently off the mark. These were neither minor nor occasional, they were constant and interrupted the expression of any coherent idea.

Worse, in the Larghetto, Lupu started to pick up the same mannered style that the conductor had established. This indicated that the pianist had no clear idea what he wanted to say about the music, nor a clear way to say it. Instead, he seemed to be trying to figure it out as he went along. While Lupu’s own cadenzas were crisp and made good use of Mozart’s material, they couldn’t rescue this performance, which was dull when it wasn’t painful.

Then there were the symphonies, which were not only exciting but superior in every way. The orchestra played “Jeremiah” with a muscular energy that not only brought out the best in the music but was itself an ideal expression of the confident strength and power of the great mid-20th century American symphonies.

The playing was so vibrant that if one closed one’s eyes, the mind told the ear it was listening to a great Koussevitzky performance, or even one led by Bernstein himself. But neither of those conductors had the sound of the Philadelphia Orchestra, each section like part of a mahogany inlay. Nor did they have the luxuriant, lustrous mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke to sing the “Lamentation” in the final movement. Cooke had as much earthy passion as the orchestra.

The musicians had even more for the Schumann performance. Working from memory, Nézet-Séguin led playing that swung back and forth between surging vitality and sheer gorgeousness. It was gratifying to hear this remarkable symphony played with such heart and commitment.

Where Mozart placed his angst into a beautiful package, Schumann used this symphony to step out of his own crippling depression. There is a feeling of constant transition, even in the slow movement, and the orchestra played with sensational momentum.

Nézet-Séguin choose his emphases judiciously, like the triple exclamation point at the first great climax in the opening movement, and the wrenching soulfulness in the Adagio espressivo.

Energy, purpose, and feeling have brought this conductor to prominence, and this performance was as fine an example of these virtues as his thrilling leadership of Der Fliegende Hollander this spring at the Metropolitan Opera.

Esa-Pekka Salonen conducts the MET Orchestra 8 p.m. May 31. The all-Mahler program offers the Symphony No. 1 and songs from Des Knaben Wunderhorn with soloists Susan Graham and Matthew Polenzani. carnegiehall.org