A sublime Adagio forms the cornerstone of Barenboim’s Bruckner Sixth

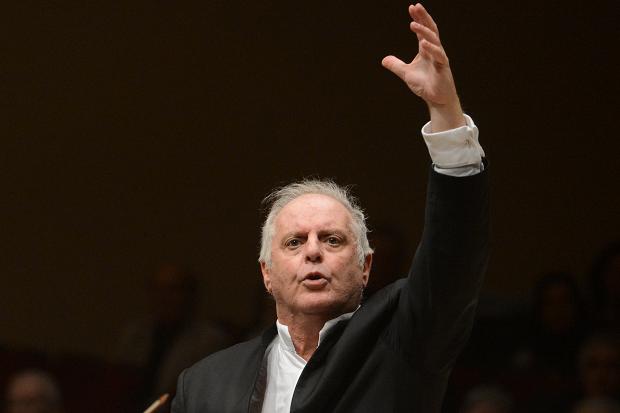

Daniel Barenboim conducted the Staatskapelle Berlin in Bruckner’s Symphony No. 6 Wednesday night at Carnegie Hall.

Of Anton Bruckner’s nine numbered symphonies, the slow movement of the Sixth, marked “Adagio: Sehr feierlich” (“Slow: very solemn”) is one of his most sublime creations. Though its melodic line is not complex, the composer devised a harmonic progression, coupled with masterful orchestration, that etches the notes in the brain. Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin delivered them with consummate ease Wednesday night. Piercingly gentle, the melody seemed to float up from the conductor’s core, flowing through his arched arms and out through his fingertips.

In the sixth of nine Carnegie Hall concerts devoted to the Bruckner symphonies in chronological order, the ensemble offered celestial focus and playing during this utterance, as well as in the symphony’s other three movements.

Using no score (as he has for most in the series), Barenboim led the first movement, marked “Majestoso,” with the assurance of a driver at the wheel of a Porsche. Gone were the chugging motifs of the Fifth Symphony (glorious on the previous night), replaced with more pastoral tranquility, albeit with rapid undercurrents, teeming with life. A reappearing unison brass line—magnificently handled by the orchestra’s players—was just one of the high points, followed by the trumpets, escalating the tension with plumes floating high above. Soaring passages, often framed by silence, were even more dramatic, helped by a rapt Carnegie audience. (A handful of ill-timed coughs during these concerts have not diminished the pleasures.)

A gigantic, amplifed fanfare marks the Scherzo, which leaps up and grabs listeners by the throat. But Bruckner tempers that with softer felicities, such as light, almost humorous pizzicatos that could populate a Tchaikovsky ballet. As the double basses maintain a pulse, the brass section continues to rain down until the end, where they eventually annihilate everything else in their path.

Barenboim showed utter relaxation in the finale, which begins with scurrying strings, with more brass outbursts peeking through—outbursts that begin to increase in fervor. As in all of the previous nights, the conductor showed masterful dramatic instincts—extreme dynamic contrasts were everywhere manifest, and this ensemble knows how to deliver a real pianissimo. Near the cataclysmic end, a single wave of Barenboim’s hand produced a corresponding weighty arc in the ensemble.

Before intermission came Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 22 in E-Flat Major, lively with off-kilter harmonic interest and orchestration. In the opening movement, beautiful suspensions, first in the horns and then the flutes, were just the beginning of dramatic interplay among the instruments. The orchestra sounded sleek and vigorous.

But despite those virtues, when Barenboim entered as piano soloist, rhythms and tempi were not yielding Mozartean clarity. As on the first night, with Piano Concerto No. 27, the orchestra was sometimes just a hair too fast or too slow, trying to keep up with the pianist. Nimbly played ascending and descending scales had lustrous piano tone but rhythms were sometimes blurred. Barenboim has offered much musical common sense during these concertos, but some Mozart fans would likely prefer more precision in execution.

Other welcome moments: a chamber music interlude with the pianist in intimate dialogue with the two first-desk players of each string section, and a later one with the group’s winds. And Barenboim’s instrospective takes on the cadenzas in the first and last movements were ideally judged.

When this glowing orchestra performed a complete cycle of Mahler symphonies in 2009, also at Carnegie and jointly conducted by Barenboim and Pierre Boulez, there were oceans of fine moments, but also some that reflected fatigue. None of that has been in evidence in the symphonies here. Over six Bruckner concerts so far, the cumulative focus and stamina shown by this ensemble have been nothing short of astounding.

The Bruckner cycle continues 8 p.m. Friday, with Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin performing Mozart’s Sinfonia concertante in E-flat Major, K. 364, and Bruckner’s Symphony No. 7. carnegiehall.org.