Despite uneven music, Terezin program makes affecting impact

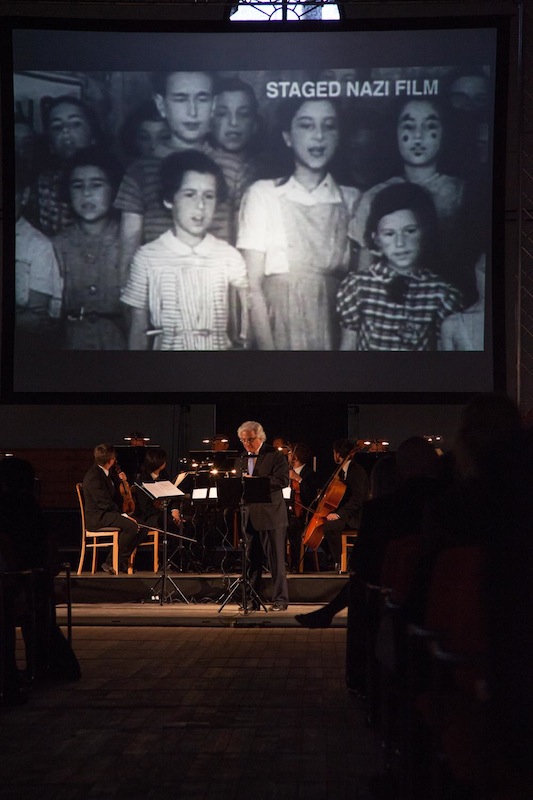

The Defiant Requiem Foundation presented music by Terezin composers Thursday night at the Bohemian National Hall. File photo: John Carpenter

Stalin likely did not say, “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic,” but it is something of a perverse comfort to imagine that exceedingly cold-hearted truth come out of his mouth.

And so the Holocaust comes to us most commonly as a statistic so awful, so many millions murdered, that the tragedy of it can be hard to feel. The numbers stun the imagination, and are so bluntly and self-evidently shocking that one responds with the mind more than the heart.

Presented by the Defiant Requiem Foundation “Hours of Freedom: The Story of the Terezín Composers” attempts to counter that by giving us several handfuls of individual composers. An ungainly hybrid of musical and theatrical performance, lecture, and historical multi-media narrative that was experienced Thursday night at the Bohemian National Hall, “Hours of Freedom” works, but in a strange way. Despite some crippling flaws, it succeeds in turning the statistics into affecting tragedy.

Terezín was a garrison town in Bohemia turned into a combination Jewish ghetto and concentration camp. The Nazis murdered Jews there, and sent others along to other concentration camps. It housed a substantial amount of the cream of Czech Jewish intellectual and aesthetic culture, and life there—such as it was—included classes, lectures, music, and art.

“Hours of Freedom” seeks to celebrate the composers and their music through short works and excerpts, 18 musical examples in all from 15 figures. There were several notable artists heard, including Viktor Ullmann, Pavel Haas, Hans Krasa, and Karel Berman (of those names only Berman survived). Others were represented as well, both those who continued to write in 19th century idioms, or who were never given the chance to live long enough to become the composers they might have been. All continued to work for as long as they were able, and that is the lens “Hours of Freedom” wields, exploring “the need to create new music as an affirmation of the future,” in the words of the program’s creator and conductor, Murray Sidlin.

This is undeniably emotionally compelling stuff—the life of the mind and the limits of human aspirations in the most horrible circumstance. \

In this context, it was jarring to hear some of the music. The opener, Ilse Weber’s sentimental, Schumann-esque Ich wandre durch Theresienstadt, (sung by mezzo-soprano Leah Wool), immediately opened up a troubling trap door: are we to feel equally sentimental about Terezín, and must we entirely suspend critical thinking and laud mediocre music due to its historical circumstances?

Because in truth, the bulk of the music presented Thursday was mediocre or worse. Works like the third movement of Gideon Klein’s String Trio, Viktor Kohn’s Praeludium, and Egon Ledec’s Gavotte for String Quartet were rudimentary and banal, while the cabaret music of Karel Svenk and Martin Roman, and Robert Dauber’s light Serenade for Violin and Piano, were competent but forgettable.

Yet the narration, delivered by Sidlin, along with a pedantic, theatrical manner by actor Jane Arnfield, commanded us to think of Leonard Bernstein as the “American version” of the young, handsome Klein, and Dauber “a major talent,” who wrote just one piece. Perhaps Klein and Dauber (murdered at 25 and 22 respectively) might have become memorable composers, but the tragedy of Terezín may ennoble their memories but it can’t improve their music.

Ullmann, Haas, and others had more meaningful things to say, and made work that lasts. Philip Alan Silver played the second movement of Ullmann’s strong Piano Sonata No. 7, and the Hours of Freedom Chamber Players, Wool, soprano Arianna Zukerman, and tenor John Bellemer sang bits from a scene of the posthumous opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis. The musicians also played the lovely, pastoral second movement of Rudolf Karel’s Nonett, and Silver gave a restrained rendition of Berman’s well-known, haunting Auschwitz – Corpse Factory. In the most troubling moment of the night, though, the ensemble played along with the notorious Nazi propaganda film of the camp performance of Haas’ Etude for Strings.

The concert closed with a chamber reduction of Martinu’s despairing Memorial to Lidice, composed and premiered in response to the Nazi’s extermination of that town.

Still, and despite all this, “Hours of Freedom” did something vital by giving us each name, from Dauber to Weber, showing us their faces, and bringing to life some of their work. We saw the individuals as human beings with minds and souls, almost all of them murdered, simply for being different. This is not a statistic, but a profound, abrading tragedy.