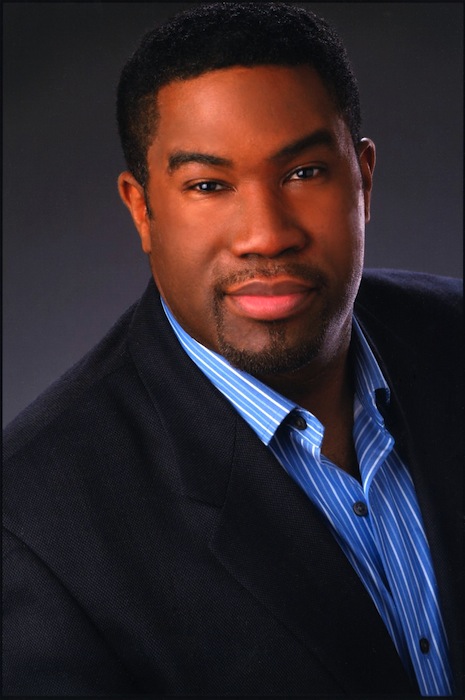

Owens shows godly authority as Wotan with Gilbert, Philharmonic

Eric Owens performed Wagner and Strauss with Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic Thursday night. Photo: Paul Sirochman

Bass-baritone Eric Owens is the artist-in-residence at the New York Philharmonic this season. At a relatively young age of 45, he has already built an impressive career on the opera stage. But what he did with the Philharmonic Thursday night in David Geffen Hall was unique and notable in the extreme.

Owens sang Alberich in the Metropolitan Opera’s 2011 Ring cycle, a natural fit for the imposing low range of his voice. On the opposing dramatic side, the character of Wotan is, in the fussy received wisdom of operatic vocal categories, a role that calls for an entirely different singer, with a higher range, a more lyrical quality, and the ability to convey regal bearing.

Owens, who is scheduled to sing the role of Wotan in the Lyric Opera of Chicago’s next Ring cycle, showed himself just as natural and commanding as a conflicted god as a scheming dwarf in Thursday’s concert performance of the final scene of Act III of Die Walküre. That scene, preceded by the Ride of the Valkyries, made up the finale of the concert. In it, Owens, the orchestra, and conductor Alan Gilbert were joined by soprano Heidi Melton, who sang Brünnhilde.

The evening began with Sibelius’ En Saga. Based on their playing Thursday night, and their performances of the Swan of Tuonela, Finlandia, and Symphony No. 4 last month, Gilbert and the musicians should be playing Sibelius far more frequently. They produce an ideal sound for the composer’s music that is warm or icy as needed, with clearly delineated and blended instrumental colors. The subtle way they make a pulse while creating the illusion that time is standing still shows genuine mastery.

Before the Wagnerian second half, Owens and Melton sang three Strauss songs, a substantial warm-up for the heavy lifting to come. Making her Philharmonic debut, Melton sang two of the four Op. 27 songs, “Cäcilie” and “Ruhe, meine Seele,” followed by Owens in “Pilgers Morgenlied,” Op. 33, No. 4.

Melton was excellent the entire night. Her rounded, full tone, projection, and precise articulation are ideal for this music, and she glided and floated over the orchestra’s responsive accompaniment, alighting on the cadences with musical and expressive logic, naturally conveying the love and anxiety in the songs. In “Pilgers,” Owens was less expressive than Melton. His voice was full and strong, but his singing—the text is a rapturous poem to love by Goethe—seemed to aim for understatement, and came off stiff and contained.

In the second half, however, every note from Owens crackled with verve and characterization. Wotan was in Owens’ voice, alternately tender, angry, anguished, but always full of dignity.

The final scene is one of the key dramatic moments in the entire Ring cycle, where Wotan must punish his daughter, Brünnhilde, for disobeying him. Wotan strips his daughter of her godly status, exiles her to sleep on a rock, surrounded by magic fire. It is there where Siegfried will find her, and thus the end of the gods begins.

As with the Strauss, the orchestra’s accompaniment was superior, conversing with the singers as another, equal character. Gilbert has shown through the years that he is a fine opera conductor. His precisely calibrated dynamics and grasp of dramatic shape made the Valkyrie music an exciting prelude to the scene.

The singing was exceptional. Melton and Owens did everything with their voices—their few gestures were nothing more obtrusive than a glance in one direction, a momentarily lowered chin or shoulder. Each singer had a clear idea of the meaning of the music and the feeling of the characters in their minds, and this came through in their shadings of dynamics, the slightest hesitation in a phrase or the attack on a sustained note, the subtle placement of their voices in the body.

The dialogue of regret between the two characters, in which each takes responsibility for the other’s faults, was affecting on a personal level. Melton seemed to rise up with love and pride, then shrink with shame. In the final pages, Owens sang the lines “With this the god now turns away from you/with this he kisses away your godhood!” with a deeply complex mix of authority and anguish.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday and 7:30 p.m. Tuesday. nyphil.org