Ashley’s “Quicksand” makes a lonely, affecting coda

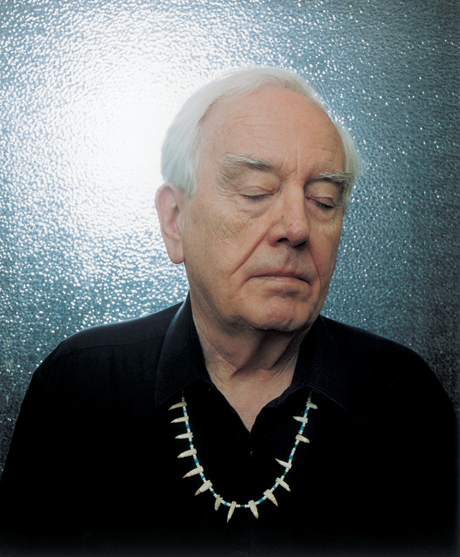

Robert Ashley was not only our most important contemporary opera composer, but also one of our finest prose writers. Through vernacular American speech, Ashley’s characters show their beliefs, their desires, their self-delusions, and their regrets.

Ashley produced a vast menagerie of characters and his insight about and empathy towards them makes for a Whitmanesque portrait of our society. His operas can be heard, and read, as a continuously revolving cycle that could also be a contender for the great American novel.

Toward the end of his life, he wrote a novel, Quicksand. He called it a libretto “written in the form of a novel,” and Thursday night, almost two years after his death, the opera Quicksand premiered at The Kitchen.

Ashley initiated the production in 2012, asking choreographer Steve Paxton and lighting designer David Moodey to create scenes for the story, and working with his long-time collaborator Tom Hamilton to create the electronic orchestration. Hamilton also recorded Ashley reading the book, and the composer’s distinctive dry, gentle speech-singing is the only voice heard in this wrenching production.

Quicksand is the first person narrative of an opera composer, old enough to be a grandfather, who also has a long-standing and active second career as what he calls a “messenger” for a government organization he calls the “Company.” The composer is a spy, traveling undercover and delivering packages to—and retrieving them from—foreign countries.

On one such trip to a small, unnamed Southeast Asian country, in the company of his wife’s yoga group, the composer befriends and earns the trust of a tour guide, a young woman he calls Pooh. She, it turns out, is one of the leaders of a revolutionary movement to overthrow her country’s military dictatorship, and she asks the composer to assist. He does so, in the company of four efficiently deadly American mercenaries he dubs “The Steelers.”

We are far from the familiar opera world, but still at the center of operatic tradition. Political revolution is no stranger to the opera stage—it was a staple of Verdi—but genre storytelling has been missing. While opera was once a genre entertainment all its own, with a vital vernacular strain, since the nineteenth century opera has increasingly become a form that regards itself as aesthetically (and class-wise) above the dominant contemporary narrative forms: genre films and novels, cartoons, and comic books.

And while this production of Quicksand is appreciably different from other Ashley operas, especially the most recent Crash and The Old Man Lives in Concrete, it fits in easily with his body of work.

Ashley’s own narration and dramatic concerns for characters, morals, and ethics are familiar, as is the music and form. Ashley worked with strict numerical structures, and Quicksand is in 16 scenes, accompanied by a 16-chord sequence that Hamilton derived from Ashley’s el/Aficionado. The result is a gently drifting harmonic underpinning with complex electronic timbres and the bright edge of four, five, and six note chords

The choreography, danced by Maura Gahan and Jurij Konjar, with cameos from Paxton, is a new element. The movement varies between abstraction, representation, and a literal replication of what is happening in the plot, including the somber depiction of a man sitting at a desk, typing.

Moodey’s lights dance too, with a colored spotlight frequently sweeping the stage and the walls, looking for something, turning up nothing. At times, the lights come up half-way, revealing clouds of smoke doing slow arabesques in the air, a beautiful emptiness.

Quicksand is full of loneliness and despair. These sensations are unsentimental, upsetting, and affecting. Taken with the plot’s unsettled ending, they present a character who is ambivalent, not because he feels nothing but because he feels so many things and can’t sort them out or resolve them. This is characterization that is impossible within the rigid constraints of the dominant grand opera style, where character have big, clear emotions that compel them to sing with grand gestures.

Ashley’s work is not only apart from the world of grand opera but from the mainstream of contemporary opera. While even this year’s PROTOTYPE Festival reflected contemporary preoccupations, those operas were still made with dramatic and musical models that are 200 years old.

Quicksand has a contemporary sensibility and also reflects how opera can work in a world with Raymond Chandler, Last Year at Marienbad, Nights of Cabiria, and television news. It is a noir opera—one man trying to guide himself through a corrupt and violent world. He succeeds for the moment, but that may only be temporary, and the cost may have been too high.

Quicksand is quiet and the music is unconventionally simple, an opera without arias and a dance without ballet. It is an opera of our world, enormous and insoluble. It is also challenging, unsettling, and at times emotionally confusing. But then so is the world.

Quicksand continues through February 6 at the Kitchen. thekitchen.org