Chamber Music Society brings joy and eloquence to Bach Brandenburgs

Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos were performed by the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Friday night at Alice Tully Hall.

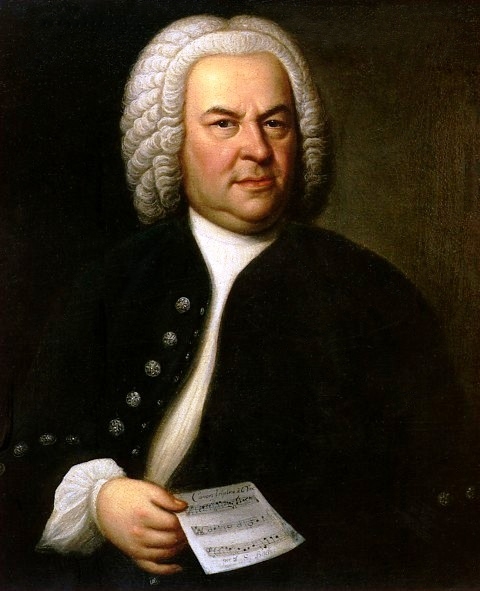

A pillar of classical repertory and a New York holiday favorite besides, Johann Sebastian Bach’s pioneering and somewhat accidental Brandenburg Concertos have managed to avoid whatever cultural fatigue might be anticipated for such familiar and inescapable music.

As their 300th anniversary approaches (in 2020), these six pocket symphonies–assembled ad-hoc as a kind of job audition—are as beloved as ever for their formal beauty, melodic indelibility and all-around essential Bach-ness.

A rousing performance of the complete set by the Chamber Music Socety of Lincoln Center night Friday night at Alice Tully Hall,, was further proof of the music’s eternal appeal and vitality, and the immense satisfaction it still offers to players and listeners.

The Brandenburg suite demanded the full talents and attention of every instrumentalist — 20 in all, in different groupings. But the CMS musicians were also audibly, and visibly, delighting in the work, in all of its rigor and loveliness, from the exquisite details to the glorious whole. Their spirited devotion to the music on Friday earned them a rapturous audience response.

Playing the six concertos “out of turn,” in a sequence of their own choosing, the musicians opened with the baroque master’s designated first piece, No. 1 in F Major, but diverged from there, going 6-2-5-3-4.

It was an agreeable ordering that sounded more cross-pollinated and congenial, and less partitioned by instrument. (The Bach-approved sequence favors winds and brass in Nos. 1-3, and strings in Nos. 4-6).

The sequencing also played into one of the music’s greatest features: the dynamism of its arrangements. The contrasts that Bach created through different orchestral groupings — larger, then smaller, and back again — are as blissful as his melodies.

When the strings fell quiet in the Trio section of Concerto No. 1, for example, there was a sweet, wending quality to the interplay of the two oboes (James Austin Smith and Stephen Taylor) and the bassoon (Marc Goldberg), and joyfulness when all of the instrumental voices returned in the Polonaise.

That heady sensation of joining — of reunion — was just as euphoric elsewhere, especially in the second Allegro of Concerto No. 5 in D Major, a blooming of strings that followed a spare, almost bleak Affetuoso that consisted of violin (Erin Keefe), flute (Demarre McGill) and spindly harpsichord (Kenneth Weiss).

Whether more equated with merrier in Bach’s conception of the Brandenburg concertos, that was the effect, if not the message, that CMS expressed with its performance. The more populated and mixed musical settings, with strings and winds together, yielded the most consistently eloquent playing.

The one hitch in the program, maybe tellingly, came in the Adagio of Concerto No. 6, whose slow interpretive quality seemed slightly out of reach for the seven players on this occasion.

The strings made a convincing comeback, however, with the more uptempo and regimented Allegro of Concerto No. 6. They did their best work in Concerto No. 3 in G Major, arranging themselves on stage in a facing semi-circle that emphasized the convivial nature of the piece.

Bach’s musical choreography in No. 3, a friendly volley of hand-offs between low and high strings, produced an entertaining visual component, too, as the musicians leaned into their cues and addressed their instruments with gusto.

If any ensemble could have walked off with bragging rights for best of show, it was the group of 11 joining forces for Concerto No. 2 in F Major. With its elaborate trumpet work, and its sweeping, high-to-low emotional and tonal range, No. 2 is both demanding and dizzyingly pretty, and trumpeter Brandon Ridenour sailed through the impossible aerial solo role with technique to burn.

Yet Concerto No. 2, like many of its companion pieces, also manages to be courtly — presumably in keeping with the circumstances of its creation: Bach trying (unsuccessfully) to get paying work from a Prussian prince, the Margrave of Brandenburg.

Bach sent the prince six pieces from different stages of his output, with new compositions included and some unifying revisions of earlier pieces tacked on — and never heard back.

The concertos thankfully survived the regal indifference. Today they’re hailed for, among other attributes, how they built on the Italian concerto grosso style, collapsed boundaries between chamber and orchestral play, and gave smaller groups a wall-of-sound capability.

Their grouping under one name is more circumstance and hindsight than author intent. But as CMS closed the program on Friday with Concerto No. 4 in G Major, there was no earthly reason not to hear it as a kindred piece. After all, that was good enough for Bach.

The program will be repeated 5 p.m. Sunday and 7:30 p.m. Tuesday at Alice Tully Hall. chambermusicsociety.org/seasontickets/event/1929/