Saygun’s distinctive voice highlights Summergarden concert

Ahmed Adnan Saygun’s String Quartet No. 3 received its belated New York premiere Sunday by the New Juilliard Ensemble.

The conditions were difficult Sunday night in the Museum of Modern Art Sculpture Garden—86 degrees in the shade, and humid for the second and final classical Juilliard Concert in the museum’s Summergarden program.

The performers were a string quartet made up of current members and alumni of the New Juilliard Ensemble—violinists Nikita Morozov and Isabel Ong, violist Isabel Hagen, and cellist Issel Herr. Their concentration on the program’s three pieces was impressive—playing outside is always a challenge, regardless of the weather—and made it easy to disregard the distractions of the heat, environmental noise, and uncomfortable seats, and just listen to the music.

The program’s subtitle, “New Music For String Quartet,” was misleading. All the music was new to New York audiences, but the first piece, Ahmed Adnan Saygun’s String Quartet No. 3, was neither recent nor “new” in its form, structure, or language.

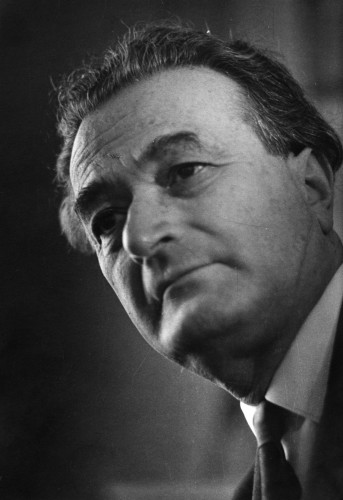

Saygun was a 20th-century Turkish composer and ethnomusicologist, and a one-time collaborator with Bartók in folk music research. His third quartet dates to 1966, and has clear roots in both Bartók and Balkan folk music while never sacrificing the sound of Saygun’s individual voice.

The music alternates dusky, languid passages and energetic riffs throughout the three movements. The slow music is colorful and evocative, developing more agitation and turbid expression with the first violin breaking through the surface with energetic, upward lines. Passages like that, and Saygun’s use of short, aggressive phrases and expressive glissandos, are modeled after Bartók.

But Saygun was not an imitator. Just as a composer writing a fugue can follow Bach without aping him, Saygun deploys techniques that Bartók pioneered to express his own value and ideas. The feeling is both modern and ancient, and satisfying. The quartet has a fine form, with an inward-turning second movement, and music that sounds highly vocalized in the energetic finale.

After a break, the musicians finished up the concert with music from Suzanne Farrin and Mark Grey. Farrin’s Undecim is in ten short movements, in contradiction to its title. The searching, expressive language of the music chimed with her program note, that describes the piece as an exploration of how musical memory—in the ears and the muscles—can intrude on everyday thinking.

The description implies a fragmented style, but the music is fluid, the memories shifting seamlessly as they do in a dream. Underneath the emotional concept she tries to express, Farrin has written a strong exercise in how to gather seemingly unrelated material into a coherent whole. The musicians gave what seemed an ideal performance.

Grey’s Sparrow’s Echo was too coherent for its own good, it could have used something rough, asymmetrical, or surprising.

Best known as the sound designer for John Adams, Grey has a substantial body of compositions to his credit. Sparrow’s Echo is a response to Mary Doria Russell’s excellent science-fiction novel, The Sparrow, about an encounter with alien species. The music begins with an attractively bright and agile fanfare, but quickly, and disappointingly, turns rote. Grey uses repetition without development, placing one episode after another. The form is clearly narrative, but the overuse of limited material makes it all plot and no story.

The musicians played energetically, even through a lot of unidiomatic string writing, but the literalness of the music set a firm limit on what they could achieve.