Fine singing enhances BAM’s odd yet entertaining “Semele”

Baroque opera is no longer the latest thing on the stage in the 21st century, but compared to works from the romantic era, even Handel is infrequently produced. The themes and context of his works make them both fresh and mutable for new interpretations.

Handel’s great Semele is even more mutable than most. Handel originally shaped the score as an oratorio, though the drama and interaction of the characters is inherently suited for opera, aided by the elegant, witty verse of William Congreve’s libretto.

The Canadian Opera Company has brought a recent production of the opera by Zhang Huan, to BAM, which opened Wednesday night. (The staging is a 2009 co-production of the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels and the KT Wong Foundation). The Chinese artist pushes Semele into a shape that is far more personal and unique than usually found on the stage, and his ambition is uneven yet fascinating.

Much of the singing and the production is gorgeous, some is wan, and a few heavily underlined elements are incongruous—they either don’t work or don’t work they way there were intended.

The set, a 450-year-old Chinese temple, is the first part of the staged story. During the overture—played unusually legato and led with a hazy downbeat from conductor Christopher Moulds—the audience saw a short, odd black and white documentary film that showed the backstory, the dismantling and relocation of this abandoned, decrepit temple.

As a stage set, it is impressive and versatile, with a monumental quality that sets off the beautiful costumes by Han Feng. In Act I, the edifice is the temple in which Semele—-the excellent Jane Archibald—and Athamas (countertenor Lawrence Zazzo) are to be married. For the second act, it becomes the garden were Semele trysts with Jupiter (tenor Colin Ainsworth), and sets the scene for some sensual rutting from the chorus. At the start of Act III, the temple becomes the sky in which Somnus—bass Kyle Ketelsen, who also sings Cadmus—dwells, next to a topless, nubile maiden and a giant, sleeping blow-up doll. At the finale, the set can be seen as a public space, perhaps Tiananmen Square

The story is roughly how Semele met Jupiter and mothered Dionysus, but with Congreve and Handel it’s a sex farce with a touch of tragedy at the end. The score is among Handel’s best, and has to be, because the plot is full of extraneous characters and unresolved elements.

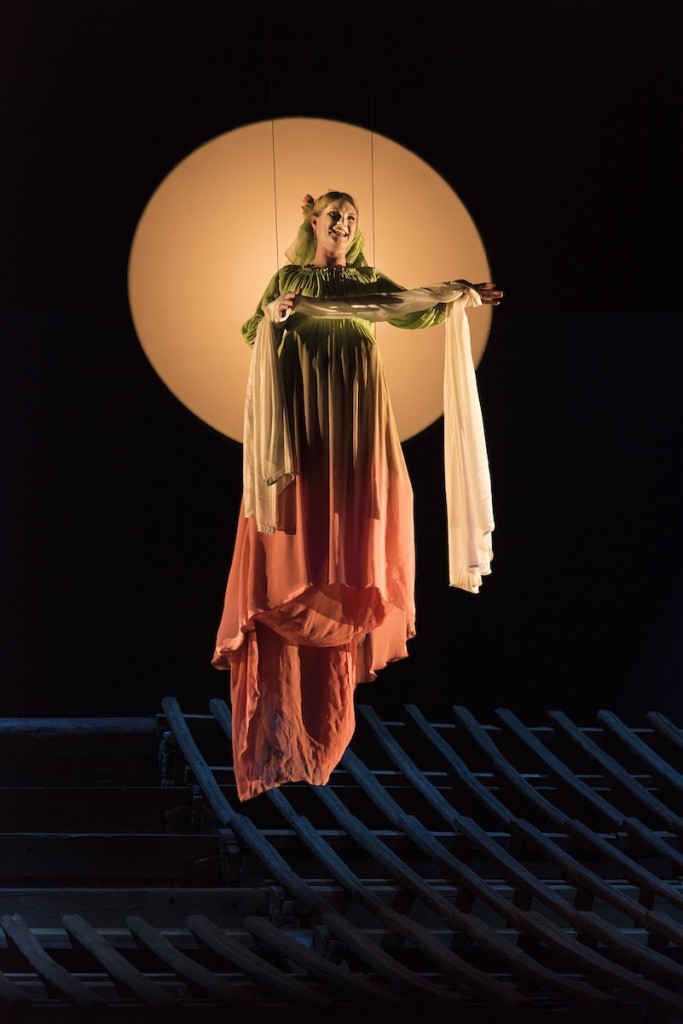

That was mostly irrelevant, especially when the women were singing. Archibald was a solid actor and a dazzling singer, handling the demanding and exhilarating ornamentation with precise rhythm, articulation, strength, and tonal clarity. The music grows more spectacular as the opera moves along, from “O sleep, why dost thou leave me?” to “Myself I shall adore,” and Archibald got better with every note.

Soprano Katherine Whyte, in the small role of Iris, was just as accomplished. There was a great vocal contrast in the contralto voice of Hilary Summers, who sang Ino, Semele’s sister, and Jupiter’s sister and wife, Juno. Her lush, throaty color was a stimulating, even eerie, companion to the bright sopranos.

The men were not at the same level. Zazzo was warbley at the start, though his singing did firm up before the end of Act I. Ketelsen and Ainsworth did not consistently get through their own challenging up-tempo ornamentations, and Ainsworth at times seemed fatigued, though he had a strong second wind in Act III, and was affecting in “Ah! Whither is she gone.”

Huan, with assistant director Allison Grant, had principals and chorus interacting actively and naturally. There are some powerful ideas in the staging, including a reflective scrim that drops down for Semele’s aria on her own reflection “Myself I shall adore,” and show the singers and the audience’s regard. When Jupiter realizes his beloved Semele is doomed because she demands to see him in his true form, he curls up in sorrow, comforted by a large Chinese dragon puppet.There’s also a two-person, costumed, dancing horse, which is enjoyable and, in a welcome explicit nod towards both the sexuality in the opera and the origins of the myth in fertility rituals, sports a comically enormous erection in Act II.

And then there are the incongruities. What goes on in and around the temple is often terrific, sometimes flawed. At the close of Act I, Tibetan singer Amchok Gompo Dhondup sings a traditional song, interpolated into the end of the Act. It’s arresting, but puts an abrupt end on the impression Handel leaves. The chorus has the last number in Act II, and they are joined by a pair of sumo wrestlers, who do their thing. It’s certainly entertaining.

At the end, Huan has removed the final scene, where Apollo arrives to bring happiness and the pleasure of Bacchus’ birth. The opera ends with the painfully beautiful choral lament, “Oh, terror and astonishment.” As the chorus sings, a woman with a baby strapped to her back slowly sweeps the stage.

But the last music in this production is not Handel. As the chorus raises a huge, red coffin, they hum the “Internationale,” the curtain drops, and, as the singing goes along, the audience sees a brief film that shows a woman’s face, washed away by water but not totally erased. The effect is haunting, the meaning enigmatic. Is Communism in the coffin along with Semele, and if so, why should we lament its end? The production births a question, a rare and stimulating experience at the opera.

Semele continues through March 8. bam.org