Argento Ensemble offers an earthy, profound “Das Lied”

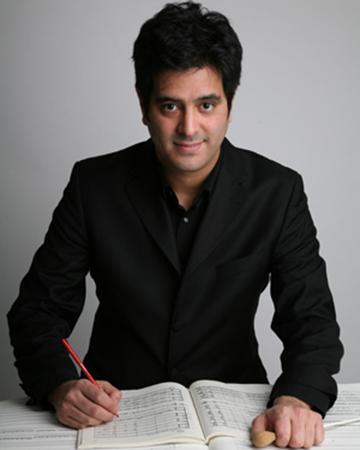

Michel Galante led the Argento Ensemble in the chamber version of Mahler’s “Das Lied von der Erde” Thursday night.

Gustav Mahler spent three years in New York City, from 1908–11, where he first conducted the Metropolitan Opera, and then led the New York Philharmonic for the 1909–10 season and part of the following one, until illness forced him to return to Europe, and to his death. Since then, and especially since Leonard Bernstein’s tenure, the Philharmonic likes to refer to itself as “Mahler’s Orchestra.”

That they are. But they are not the only Mahler orchestra in New York City. There is a surprising rival in the Argento Ensemble and conductor Michel Galante. Argento is know primarily for playing high modern and new music, but this season they have organized a four-concert series, “Mahler as New York Contemporary,” that sets new compositions alongside some of Mahler’s great works in chamber orchestra reductions.

Thursday night, in the Board of Officers Room at the Park Avenue Armory, the Argento Ensemble gave their second concert in the series, with recent pieces from Oliver Schneller and Jesse Jones capped off with Das Lied von der Erde in Galante’s slightly revised version of the well-known reduction by Schoenberg and Rainer Riehn. The concert surpassed their exceptional opening.

The experience began with recent compositions by Schneller, the New York premiere of Clair-Obscur (2005–06), and Jesse Jones’ Threshold (2012), a song for tenor using a poem by Rabindranath Tagore. The pieces shared a common concern with texture, the first lean, the second thick, and they were played with command and musicality.

Despite the title, Clair-Obscur had a lean, sharp profile. The piece is essentially one long horizontal line, ascending in segments. There are ensemble crescendos that presage the changes in pitch, but most of the music is made through single, sustained notes, the instruments darting at it and glancing off, passing it around. Schneller makes this work by keeping the timbres in a constant metamorphosis. The music shifts slowly, like ice floes on still waters. The piece is shaped in the manner of Ligeti’s Atmospheres. Clair-Obscur is like a razor through a cloud however, there is a hint of aggression that makes it quite involving. Percussionist Matt Ward conducted with what sounded like an ideal shape and pace.

The textures in Threshold are lush and, were it not for the vocal part, would be in place in a horror movie. Coming before Das Lied, the piece elided with Mahler through Tagore’s poem about birth and the inevitability of death. Jones setting was fascinating. The vocal line has the melodic earthiness of Britten, and the tenor, the fine Zach Finkelstein, starts in and returns to the falsetto register. Underneath there are dark, thick, textures that come in waves and add mystery to the mix.

The Das Lied reduction was initiated in 1920 by Schoenberg for his Society for Private Musical Performancem, and finished by Rainer Riehn in 1983. There have been a handful of recordings of this chamber version, occasional performances, and, recently, two new chamber arrangements.

It was never meant for public performance, however. The society was a private salon where composers and musicians could hear important modern and contemporary music. In the chamber version, a great deal of orchestral color, texture and weight is sacrificed, reducing Mahler’s expressive means. What comes through is the structure, especially polyphony, which is most interesting to the listening composer.

To this score, Galante reintroduced the trumpet and trombone parts. The trumpet has an inherent romantic quality, and returned a vital color that combined with the other instruments to create more blends and hues than in the Schoenberg/Riehn score, and the additional low end heft from the trombone expanded the ensemble’s presence. The clear, lingering resonance of the Board of Officers Room was a benefit.

As essential as those details were, what made everything work was the playing and singing, which was superb in every way. Tenor James Benjamin Rodgers and mezzo-soprano Jennifer Beattie proved ideal, handling the arduous technical demands of the music while sounding like the everyday men and women Mahler envisioned.

Beattie has a rich, throaty voice, while Rodgers eschewed superficial elegance, and used a blunt attack on many words and phrases. His singing was musical and dramatically intense—he didn’t just sing the part, he was the drunkard in “Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde.” Beattie’s entrance on “Der Einsame im Herbst,” one of Mahler’s most artful moments, was quiet, focussed and exceptionally warm, and in “Der Abschied,” her modulation from sonic and emotional desolation to lustrous consolation was beautiful.

Most exceptional was that throughout the whole piece, Rodgers and Beattie sang with an implicit understanding of the poetry, expressing not only Mahler but the earthiness and humanity that Mahler found compelling in “Die chinesische Flöte.” Their singing had a natural communication that is special and rare in classical performances—they spoke to us as if we were old friends.

Rodgers and Beattie were matched by the tremendous gusto of Argento’s playing. The ensemble’s phrasing is more modern than Viennese, an important approach in Mahler’s last works. In every other way their playing was utterly idiomatic: Galante’s smooth tempo modulations could not have been better, and the musicians listened and responded to each other avidly, making music together.

The woodwind playing was marvelous, and clarinetist Carol McGonnell and flutist Lance Suzuki were ravishingly expressive in “Der Abschied.” After Beattie sang the line “Mein Herz ist müde” in “Der Einsame,” violinist Emilie-Anne Gendron responded by playing her short, ascending solo with an uncannily eerie hollow timbre.

The classical tradition is an ongoing continuum, with new music built upon the past, and the way to honor the past is to make it alive again in the present. Major orchestras routinely play Mahler with affecting skill and musicality, but there is nothing routine about the Argento Ensemble’s Mahler, and their remarkable spark of life they gave the music Thursday night should be the goal of every classical concert.

The next concert in the series “Mahler as New York Contemporary” takes place 7 p.m. March 26 at the DiMenna Center. argentomusic.org

Posted Jan 16, 2015 at 2:17 pm by John Hohmann

Thank you for a wonderfully informative review. How fascinating that this “to the trade only” arrangement could be every so slightly reworked to bring such freshness to Mahler. The orchestra and soloists were exquisitely balanced. Coupled with the contemporary works, the evening was a thrilling and insightful event.

Posted Jan 18, 2015 at 7:51 pm by Billy Allen

Remembering the piano concerts in your house in SF.

congrats