Either/Or plays rare and ravishing Feldman at Issue Project Room

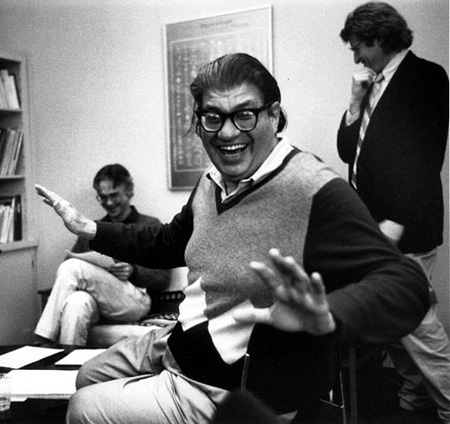

Morton Feldman’s “For Philip Guston” was performed by Either/Or ensemble Sunday at Issue Project Room.

Let’s hope that whatever has been in New York City’s air and water that has led to concerts this season of three of Morton Feldman’s longest works lingers.

Since October, concertgoers have witnessed Anton Batagov playing Triadic Memories for nearly two hours and the Flux Quartet playing the String Quartet No. 2 for close to six (both ideal performances and both held at the Park Avenue Armory). The serendipitous Feldman series finished Sunday with the Either/Or ensemble’s marvelous concert of For Philip Guston at Issue Project Room.

Concert programmers take note: all of these performances played to full houses. The crowd on Sunday afternoon filled all the available chairs and spilled out to the walls and in the lobby (three-fourths stayed to the end).

For Philip Guston does not match the duration of the String Quartet No. 2, but the concert—the last of a series celebrating the ensemble’s tenth anniversary—did approach four and a half hours in length. As with the quartet, there is neither a wasted note nor the sense of the music running out of things to say (or, as Stravinsky famously put it, finishing long before it ends).

The excellent musicianship helped, of course, yet the piece is also as sonically colorful as anything Feldman produced. The sound is ringing and rounded, scored for a keyboardist playing piano and celesta (ensemble director Richard Carrick), a flutist doubling on piccolo and bass flute (Margaret Lancaster), and the tuned percussion of vibraphone, marimba, glockenspiel and tubular bells (Either/Or cirector David Shively). The resonant marble walls and floor, and the high, arched ceiling at Issue Project Room made for a superb space for the music, with the acoustic holding the long, strangely mutating decay of dissonant piano chords and the complex overtones of the bells.

Guston begins with a four-note theme in the flute, the thread that stitches together the length and breadth of the music, with a compositional technique particular to Feldman’s music. The theme is C down to G up to A-flat then up again to E-flat—introducing the world premiere in 1985 at the University of Buffalo, Feldman said “the tune spells out ‘CAGE’, but not in that order.” The notes, and the title, are about Feldman and Cage discovering the paintings of Guston, who Feldman admired and befriended. As it moves around through different keys during the course of the piece, the theme reflects “varying degrees of representation treated abstractly,” the quality the composer found attractive in Guston’s paintings.

The technique Feldman uses is to double the theme with the piano, but with a displaced rhythm. This is the trademark of the composer’s late works: simple musical material repeated with subtle but important changes in rhythm, and this was where the Either/Or playing stood out. Other than stamina, there is very little that is technically challenging in the notes of the piece, but the musicians need to maintain a steady, clear pulse for four-plus hours so that the ear can hear the dramatic difference that one fraction of a beat makes, say, on the third repetition of a phrase.

Shively especially held a clear pulse from the start. The other musicians were equally on target, but about a half-hour in, Lancaster and Carrick seemed to suddenly hold the same pulse without conscious thinking, feeling it in their bodies without counting in their heads. The playing, which was already focused and assured, became more fluid, natural, meaningful. The musicians also controlled dynamics with casual discipline, and Lancaster held her embouchure and intonation on all three flutes—the effort she required was obvious only a handful of times, and never interfered with her playing.

The four notes of the “C A G E” theme present a major/minor key dichotomy that is unresolved and that has a haunting effect. Feldman constructs the piece out of small and large sections that are repeated. But the music works through more varied means as well: there are variations on the theme and a large form that is almost Brucknerian in its alternations between harmonically complex and melodically static sections and long, bucolic stretches where the music flows along, gently and irrevocably.

Feldman himself made visually beautiful graphic scores in the 1950s, but the triumph of For Philip Guston is that it is an old-fashioned piece of composing, the composer setting down notes, rests and expressions, his intention in every mark. The duration is deliberate, a means to direct the musicians and listeners to an experience meant to challenge and alter their perceptions.

Four hours of four-note phrases and quiet chords lead to an extended finale that goes beyond lyrical into the pastoral, the most beautiful music Feldman wrote and some of the most beautiful music of the post-World War II era. As the flute and piano play a simple, languid duet, the percussionist repeats a slow, spare, descending scale that defines A minor. If the previous music had a clear means but an abstract purpose, this music is like a song, the language common and resonant.

Five strikingly dense piano chords announce a real coda, and the bass flute plays the A minor scale. Soon after, the music stops, having said all it needs to say.