Ashley’s final opera, “Crash” marks a terminus and a new legacy

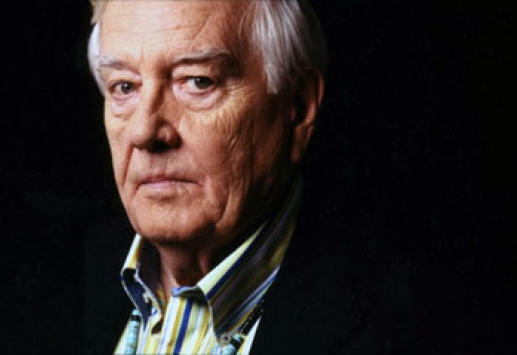

Subsumed by more familiar names of the 20th century avant-garde—Cage, Xenakis, Feldman—the opera composer Robert Ashley, who died March 3, a few weeks shy of 84 years old, was a paragon of contemporary music and the creator of major works that established a singularly American, vernacular style of opera.

Ashley’s work staked out territory conjoining music, theater, television and technology that few have entered. His operas have enjoyed a small but intensely devoted following in the music world, and, like Cage, his work found welcome reception in the art world. But Ashley suffered from the frustrations of being known more than heard, praised more than produced or paid.

As part of the 2014 Whitney Biennial, three of his operas are being presented at the museum, curated by Anthony Elms and directed by Alex Waterman. Ashley’s magnum opus, Perfect Lives, will be produced in its Spanish-language version, Vidas Perfectas, and one of his most experimental early works, The Trial of Anne Opie Wehrer and Unknown Accomplices for Crimes Against Humanity (a “speaking opera”), closes the run. Most important, his final opera, Crash, opened Thursday afternoon, in its world premiere performance.

Crash is a beautiful, affecting work, written at the apex of Ashley’s career. While the way he wrote his operas is difficult to reconcile with the standard traditions of the form, his works are approachable and aim for a time-suspending, mesmerizing quality. Crash achieves that, and has a focus and clarity that marks a distinctive late style that first appeared in his previous opera, The Old Man Lives in Concrete.

Ashley’s operas are full of people of the kind America usually ignores: ordinary folks in ordinary towns, the homeless and, especially of late, the elderly. He realizes the characters through dialogue set in strict duration and to subtle, ironclad rhythms. The characters sometimes sing, but usually speak with musical intonation, and they are accompanied in the various pieces by distinctive electronic music and obbligatos from the pianist “Blue” Gene Tyranny.

Ashley was a superior librettist, one of the finest American prose stylists, and his pieces are dense with words—words drive the rhythms and the music. They have also been dense with plots and characters, and one of their consistent problems has been that the plots require so much a priori explanation that they at times obscure the substance of the operas. Crash, like Concrete, is different.

Rather than several characters, there is one with several voices—six performers. They sit in a television studio set, which the composer had in mind as the ideal place to produce all his operas. The character is Ashley himself, and the voices have three delineated styles: one singing as if they were talking on the phone; another singing as if they were reciting a poem; the last singing with a slight but noticeable verbal tic, a slight hesitation like that of a suppressed stutter (or the mild Tourette’s Ashley believed he suffered from).

On the phone, the voice talks about the idea of cycles in life, the problem of being physically small in society, and having neighbors, good, bad and indifferent ones. The poetic voice describes recurring fainting spells Ashley experienced, the voice with the tic narrates Ashley’s life through important events. The speaking moves back and forth through three performers, while the other three quietly vocalize on sustained, rhythmically exact pitches. Then they switch, the speakers vocalize and vice-versa.

The flow of words and stories is both beguiling and fluently done—few details stick in the memory but the overall effect is deeply moving, a story of failure, success, frustration, happiness, loneliness, satisfaction and disappointment. It is lovely but also melancholy and poignant in many ways. The cycle concept, “fourteen years for men,” underpins everything, and speaks with expectation about how the sixth cycle will be a high point at age 84. Ashley received his diagnosis of cirrhosis last summer while working on Crash, and must have known he would not see that realized.

Also deeply moving is seeing an entirely new generation of performers tackling Ashley’s works: Paul Pinto, Gelsey Bell, Amirtha Kidambi, Brian McCorkle, David Ruder and Aliza Simons. They have Ashley’s idiom down exactly, and carry the quiet charisma his work demands. None of the old, familiar voices—even Ashley’s—are missed, and that has the powerful effect of cementing his achievement and stature as a composer.

Working with his composition, his unique notational methods (and with notes Ashley sent them via audio recordings), they produce the unique, engrossing quality of his operas: the captivating speeches, the vocal susurration, the humor and empathetic humanity. The inherent sadness of this posthumous premiere was balanced with the moving realization that Ashley now has a legac and left us a body of work that is a repertory.

Crash continues through April 13; Vidas Perfectas will be performed April 17 – April 20, and The Trial of Anne Opie Wehrer April 23 – April 26. whitney.org