Eschenbach, Vienna Phil offer gorgeous Mahler, uneven Schubert

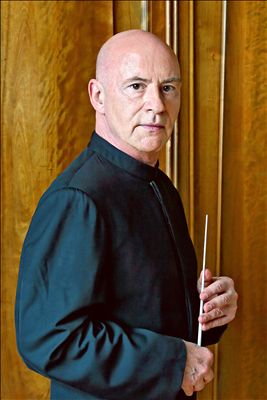

Christoph Eschenbach led the VIenna Philharmonic in music of Schubert and Mahler Saturday night at Carnegie Hall.

Saturday night, conductor Christoph Eschenbach and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra returned to Carnegie Hall for their penultimate concert of the “Vienna: City of Dreams” festival. The meat-and-potatoes program of Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony and Mahler’s Symphony No. 4, coming at the end of a long series of concerts, could have been routine, but turned out to be something quite special. The evening was an example of the kind of things a conductor can do to make and/or break a performance.

The varied possibilities of the conductor’s art and the strangely obvious way things can go wrong came during the first half, within the confines of Schubert’s two-movements symphony. The first movement was far removed from ordinary Classical interpretation. This was clear from the opening bass melody, which was played with an ominous intensity, and then completely rounded off by Eschenbach’s baton. He placed a clear and surprising break, not in the score, between the melody’s last note and the entrance of the violins and cellos, who lay down the opening harmonies.

What Eschenbach created with this bit of creative willfulness was a feeling of visceral drama. More than just melody, counterpoint and development, Schubert’s long phrases immediately became lines in an involving dialogue between instrumental groups and symphonic sections. And instead of sounding eccentric, Eschenbach reinforced his thinking throughout the entire movement, creating his own convincing logic that was an exceptional companion to the composer. The conductor blocked off the melodic sections into discrete blocks and took care to delineate them and emphasize the differences in dynamics.

He also maintained a tempo best described as careful. On the slow side of allegro, the effect was to further highlight the sectional forms in the music, and the relative slowness brought the pulse, rather than the beat, to the fore. In the grand climax in the middle of the movement, he let the pulse drop away completely, revealing a rich monolith of sound that sat in space. Eschenbach’s way was to have the orchestra play the music like it was Bruckner, rather than Schubert, and as startling an idea as that is, it was thrilling to hear. The new thinking was refreshing enough, but the color and intensity of the huge range between light and dark sections was fascinating and spine-tingling.

And then the second movement started, and everything came crashing down. The music is flowing, lyrical, the tempo Andante. The conundrum after such a slow Allegro is how to be convincingly slower, and Eschenbach didn’t convince with his stolid pace.

Worse, he took a similar approach of setting the music into large blocks, shown in contrast. But in the Andante, Schubert’s blocks don’t separate phrases, they are used to make up longer ones. The music is different and demands a different idea, and forcing it through the seive of the opening conception produced music that was choppy even though slow, and distractingly dull overall.

Eschenbach giveth and taketh away, but his Mahler restored all. The performance of the Mahler symphony was a complete success, the reason as simple as merely letting this great orchestra play the notes, express their pleasure in the sound, and, for Eschenbach, do little more than keep an eminently reasonable and idiomatic set of tempos and dynamics.

Everything was idiomatically right, everything sounded like Mahler at his gentlest and sweetest. The playing of the scherzo movement was marvelous, a subtle balance between abstraction and dance that showed the orchestra’s deep historical and aesthetic roots.

The only bit of real conductorial intervention was in the slow movement, where Eschenbach let certain passages linger, mainly to relish the beauty of the music just a bit longer. In the dark moments he prodded the players to go just a bit darker, a touch deeper, well within reason and completely effective.

There was the extraordinarily witty idea to have soprano Juliane Banse walk onstage just at the moment of the grand, “Gates of Heaven” climax, and the graceful but quick elision into the final movement was a welcome pre-emption of the expected coughing, snorting and shuffling after twenty minutes or so of spellbindingly beautiful playing.

Banse can’t possibly convince as a child-like voice, as Mahler wished, but she sang richly and joyously. At times her tempo ran on a different track than the orchestra, which kept up a lively, light-footed pace.

The Vienna Philharmonic was the star. The strings were warm and gorgeous as expected, but the woodwind section is just as strong and the brass now stands out as one of the best sections in any orchestra. As a group they play with a lovely color, full but unobtrusive presence at every volume, and a perfect blend of sound. They have the subtle and impressive musicianship to fit inside the orchestra no matter the dynamic, so that they can be clearly heard without ever overpowering the other instruments.

This was a performance that moved one through the sheer power of beauty, and showed that the most important thing a conductor can do is prepare the orchestra, manage tempos and dynamics, handle traffic when things get busy, then get out of the way and let the music flow.

The Vienna Philharmonic plays its final “Vienna: City of Dreams” concert, led by Zubin Mehta, 7 p.m. Sunday. carnegiehall.org.