Zinman, Philharmonic belatedly find their footing with Mendelssohn

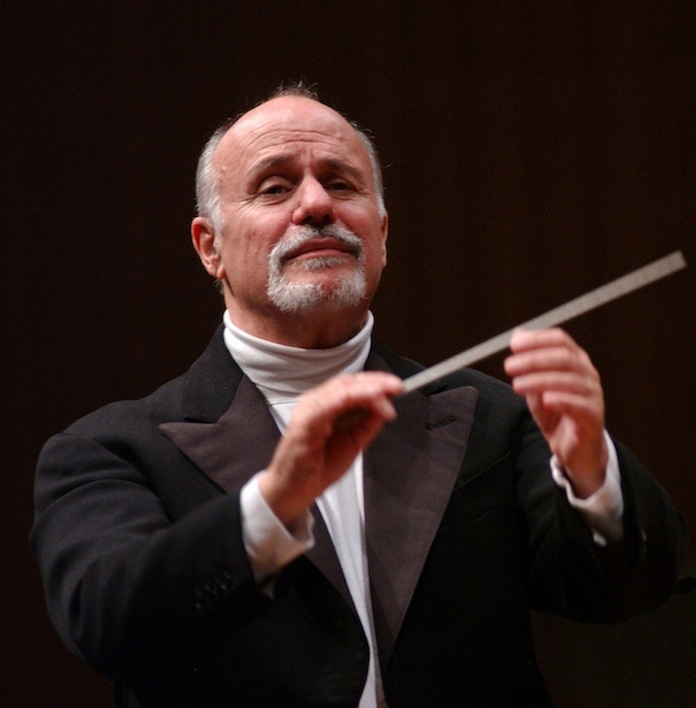

David Zinman conducted the New York Philharmonic Thursday night in music of Adès, Mozart and Mendelssohn.

The New York Philharmonic’s program on Thursday evening was not likely to offend anyone’s sensibilities. The selections on it are all potentially rewarding in their own ways, but this concert unfortunately seemed more challenging for the musicians than for their audience.

The veteran American conductor David Zinman led the orchestra, beginning with Thomas Adès’s Three Studies from Couperin. Adès was quoted in the liner notes as saying that “My ideal day would be staying at home and playing the harpsichord works of Couperin—new inspiration on every page.”

His inspiration here takes the form of curious arrangements of the concluding movements of three of the French Baroque composer’s Ordres for harpsichord. This is not the Adès New York audiences know from his opera The Tempest, but instead a set of very straightforward and personal pieces that amplify the humor—or the languor—of their sources, but which are not particularly complicated.

The Philharmonic’s performance sounded, frankly, underrehearsed. Whatever Zinman may have had in mind for his interpretation was lost as he struggled just to keep everything together. In the first of the three studies, “Les Amusemens,” Adès’s rolling melodic lines were muddled to the point that it was difficult to tell what was going on. “Les Tours de Passe-passe” was amusing and plucky, but the players sounded disorganized and hesitant under Zinman’s direction. Tempo changes were an adventure, as they continued to be throughout the night. “The Languid “L’Âme-en-Peine” was affectingly pleading, but still had no focus.

The orchestra did not exhibit much more confidence in Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 18. The exposition still showed problems of coordination, and while the writing here is certainly light and agile, their playing was more airy than spry.

Even Richard Goode, usually an artist of considerable poise and sensitivity, seemed off his game. After making his entrance at a tempo noticeably faster than Zinman’s, he was imprecise in his passagework and his interpretation felt stifled. Where it needed effortlessness, it was labored, where it needed wit, it was deadpanned.

Goode was at his best in the slow movement, treating the flowing Andante with eloquence. The orchestra was more in sync here, but the various sections still did not seem aware of each other and Zinman did not have control of balances: the strings would be playing softly under the piano, and then the winds would obliviously trundle in at full voice. Or the reverse. The opening of the last movement—marked Allegro vivace—was hollow, with no detectable bounce or exuberance. In the main cadenza, Goode seemed just to be going through the motions. His performance was truly surprising, and not in a good way.

Zinman and the Philharmonic were able to salvage the evening with a performance of Mendelssohn’s Symphony No. 3 (“Scottish”) that finished much better than it started. Their sound was thin at the beginning (which was also not quite together), and disjointed thereafter. Doleful as it is at its start, this first movement has a calm intensity, but the Philharmonic just sounded lost. The second movement had more life, though still not enough with the orchestra failing or unable to cut loose. The musicians delivered a solid, sentimental reading of the Adagio, though there was little warmth in the strings.

Only in the finale did the Philharmonic at last come together and play with a united purpose. The movement began with grinning mischief and grew into something much darker, broad and brooding, with irresistible tension, before the Allegro maestoso section interrupts with its bursting celebration. Hopefully they’ll find more of that in the remaining performances this weekend.

The program will be repeated 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday. nyphil.org

Eric C Simpson is the Hilton Kramer Fellow in Criticism at The New Criterion