Tilson Thomas, San Francisco Symphony bring a natural eloquence to Mahler’s Ninth

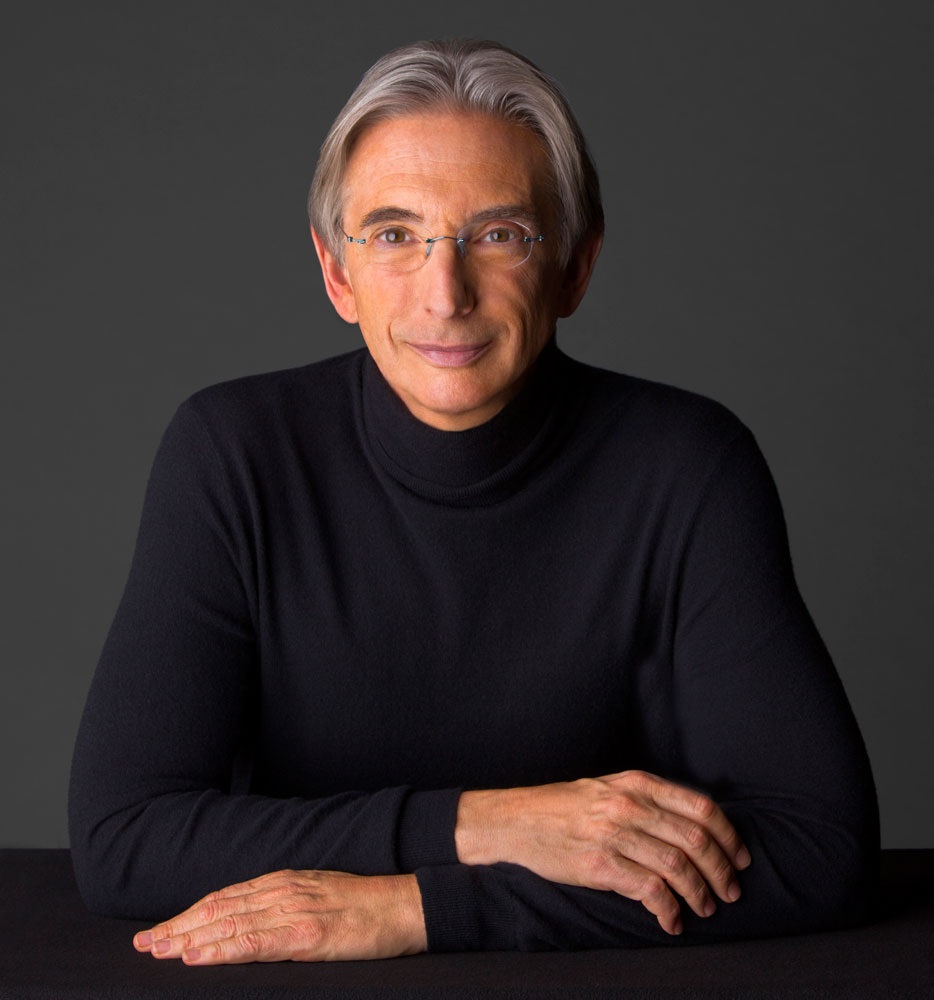

Michael Tilson Thomas conducted the San Francisco Symphony in Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 Thursday night at Carnegie Hall.

It is uncommon in the extreme to hear the two-note melody that starts in the sixth bar of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 9 tossed off in as modest and even accidental a way as Michael Tilson Thomas and the San Francisco Symphony played them at Carnegie Hall on Thursday evening. In thirty years of listening to this work, including at least a half a dozen concerts from these same musicians, this was a first.

It was also the first moment among many that revealed the deep familiarity and sympathetic, searching thought Tilson Thomas and the orchestra have with this music. The conductor is the leading Mahler interpreter of his generation, and what separates him from a peer group of the world’s finest musicians is that his ideas about the composer never rest on predictability. They are constructively restless.

Mahler’s music deserves that, especially this extraordinary composition, unique in the symphonic literature and even among the composer’s own monumental body of work. The technical and expressive freedom of the Symphony No. 9 make it New Music. There is an abstraction that is both plain-spoken and barely comprehensible, as if Beckett had used a rich, ornate vocabulary and syntax. Since it’s his final complete work, the easy logic is to fold it into the past, into the world of the other symphonies. It’s just as logical and far more exciting and rewarding to play it as the first step in a future that would never come, as a question instead of an answer.

It is restless above all else. Musical lines spin out as endless melody, not so much coming to an end on a cadence but transforming into something else. Emotional and intellectual ideas veer from one extreme to another in an instant, and hold contradictory thoughts together in sublime tension.

The two notes, lovingly cribbed from the opening of Beethoven’s “Les Adieux” piano sonata, lead to a mind-bogglingly fecund motivic development, and Tilson Thomas planted them like seeds as casually as any farmer would, then tended to them as they grew into the far-ranging emotional journey of the opening Andante commodo movement. The lack of drama at the standard moments was consistent with the opening.

In the past, Tilson Thomas has led the music as the rise and fall of climaxes, focusing care on the shape of each phrase as they fall into position and accumulate in effect. In this concert, part of the Carnegie Hall Great American Orchestras series, he took a long view, allowing the musical ideas to mix, mingle and grow in every direction. His phrase was not the rise and fall of a violin line or the ramp up to an orchestral tutti, but the many minutes from the symphony’s first sound, a dotted-quarter and eighth note, to its stertorous reappearance in the brass.

This was non-standard Mahler, but rooted in the composer’s aesthetic. It was not the alternation of light and darkness, but of motion and stasis. The timpani tattoo, the weird bass clarinet solo, happened in stopped time. The transition out became a marvelously steady, logical gathering of energy into movement.

It was one enormous phrase that fit, in the spaciously flowing tempo, into an even longer musical chapter. The series of 2004 concerts that became the San Francisco Symphony Media recording of this symphony argued that the piece is fundamentally about entropy. Thursday, the first movement still captured the relationship between organization and decay, but now that idea was part of a deeper view. This was an existential Mahler 9th. The darkness was what it found in the universe around it, the energy was its own determination to think and act.

The second movement Ländler was deceptively relaxed at first, powerful at the close. The long view held through the stages and moods of the dance to the static, mysterious music that comes just before the ending. This reinforced the clarity and conviction of Tilson Thomas’s concept.

The Rondo-Burleske was intense, and few ensembles play with the frenzy that develops like this orchestra can. But before that point, the music, which had been busy, falls away to a quiet pause with a nostalgic trumpet solo. Stillness out of motion again, and with a clarity and cogency that revealed how the notes themselves develop out of motives from the first movement.

The thinking and playing were revelatory but never idiosyncratic: the tutti chords were crushing, the wild traffic was chaotic, the peasants reeled merrily, shadowed by the devil. The strings made judicious use of portamento, giving it more expression.

This is a superb orchestra. Principal flutist Tim Day hollowed and shaded his tone strikingly in his last solo in the first movement; Jonathan Vinocour led a full-sounding viola section and soloed beautifully; concertmaster Alexander Barantschik, principal horn Robert Ward, principal bassoonist Stephen Paulson and contrabassoonist Steven Braunstein were all standouts. The brass section traversed an astonishing range of colors, from mellow to bright to a kind of contorted brittleness.

The final movement was unusually rich and warm. It always sounds good and right to play this music like the dying of the light. The strings keep trying to build rich musical structures, the rest of the orchestra interjects, forcing them off course. The strings draw down the final notes to nothing.

Tilson Thomas brought an extraordinary clarity to the final measures. Mahler’s polyphony gives way to alternating phrases in the violins, cellos and violas. The playing was unsentimental and astonishingly clear, each note presented with body, even while pianissimo. The dying of the light would have to wait until there was no more music, there was no letting go of Mahler’s creation while it still made order out of the chaos of space and time.

The Great American Orchestras series continues February 12, 2014 with the Boston Symphony Orchestra conducted by Bernard Haitink in an all-Ravel program. carnegiehall.org