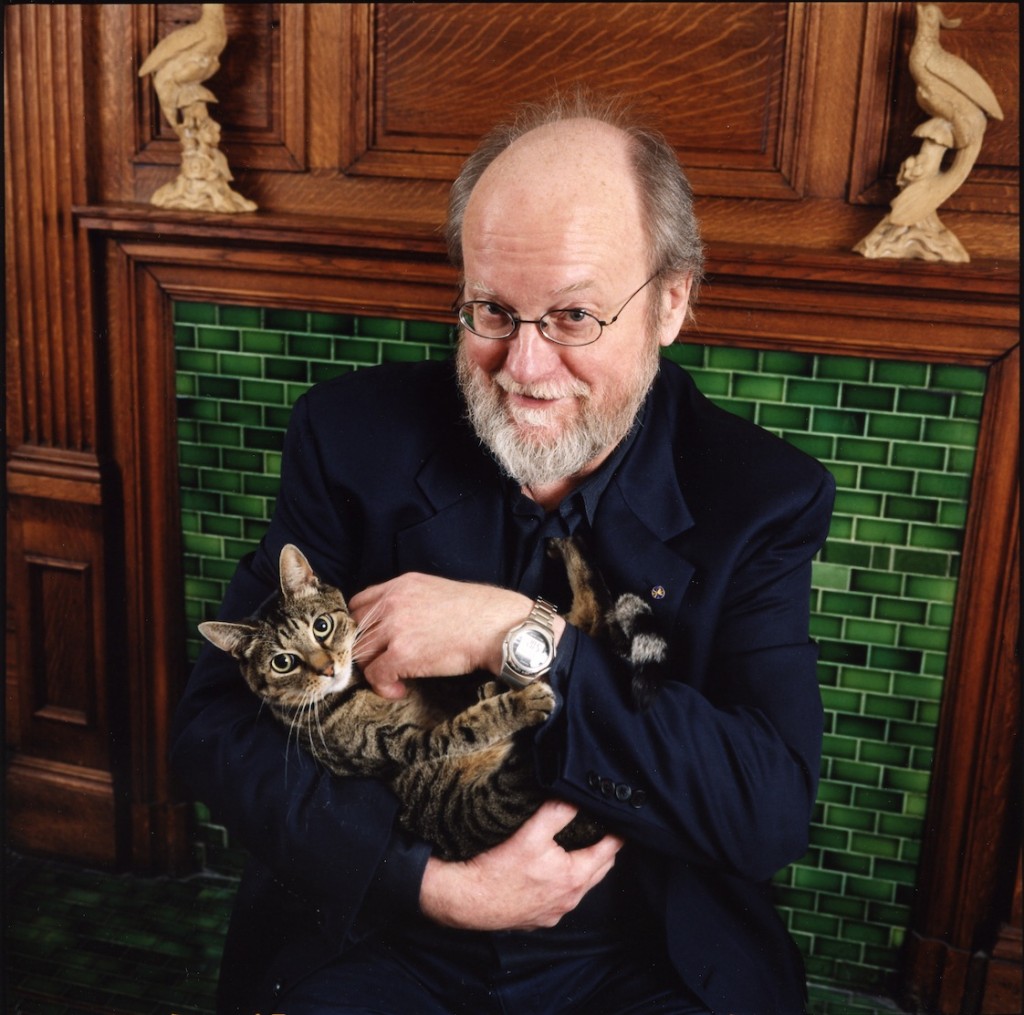

The past is prologue for Charles Wuorinen’s individual art

The music of Charles Wuorinen – who is celebrating his 75th birthday this year – is so old school it sounds new again.

There was an all-Wuorinen concert at the Morgan Library Wednesday night, a concise but powerful observance for his long and productive career. The program was made up of music for piano and for string quartet, and managed to chart where the composer came from and where he is now, albeit without touching on his extensive vocal output.

Wuorinen manages to be both familiar and modern, as a composer working within the Western classical tradition in what he calls a “maximalist” way. That’s commonly understood as his view of tonality and structure with a foundation in dodecaphonic music and Classical and Romantic forms. It’s more meaningful to expand the word to encompass the expressive possibilities of the classical tradition.

Not all the music in the concert was Wuorinen’s. The Brentano String Quartet played his Marian Tropes and Josquiniana with care and great musicality. These are works from the past ten years; the former arranges sections of incomplete liturgical works by Dufay and Josquin, the latter is Wuorinen’s “recomposition” of secular songs by Josquin. (Since they are five-part songs, Wuorinen arranges some of the lines for double-stops and adds expressive string color and technique to others.)

These pieces give some idea where Wuorinen comes from, what he listens to and what he cares about. His place in the tradition is to cherish Renaissance polyphony (the string settings make this continental vocal music sound evocatively Elizabethan) but to write in his own musical voice. The concert’s opening piece, The Blue Bamboula for piano, is a conceptual transition from past to future.

With Bamboula you get Louis Moreau Gottschalk, and there are effervescent and ephemeral glimpses of his proto-ragtime/boogie-woogie that shine through in both the upper and lower registers of the piano. The piece, finished around 1980, also has horizontal drive and a relatively spare harmonic profile that are loosely connected to Gottschalk (in the general sense that his music was more about tunes and rhythms than harmonies). It’s also, like all the piano music in the concert, a finger-buster. Wuorinen, himself a terrific pianist, demands physical and mental dexterity from his musicians, and Ursula Oppens – for whom he wrote the work – played it with characteristic skill, power, drive and intellect.

The Blue Bamboula’s constant, garrulous activity, its mix of atonality and dissonance and some consonance, display Wuorinen’s values. Those can be heard as a bridge between Schoenberg and Carter, while beholden to neither. The music is mostly atonal, but not strictly systematized, and it’s fit to a constant modulation of ideas and rhythms. There are some repeated phrases and patterns, but they are elided in the midst of thickets of ideas and are constantly heard in altered form, their shape inverted or extended.

Modern capitalism and mass-media shunted musical thinking like this aside, and it was set in amber at the universities. It developed into an academic style, even an ideology, speaking to a limited audience. A lot of the music is great, but where it fails is in didacticism and opacity.

Wuorinen, though he’s written a good composition textbook, is neither academic nor didactic. His assured, uncompromising values sound fresh and biting, like straight vodka, and the way he positions himself vis-a-vis historical tradition is positively romantic.

Maximally, the direct context for his piano music comes from Beethoven and Berg. That was made profoundly clear in his Third Piano Sonata – finished in 2002 for Alan Feinberg – and the Fourth Piano Sonata – from 2008 and written for Anne-Marie McDermott. Each pianist was exceptional in these remarkably demanding works.

The Third Sonata is in three movements that are Beethovenian, with the first in clear sonata-allegro form, a slow middle movement and an energetic finale. While the secondary theme in the opening movement has Beethoven’s structural daring, it is radically slower in pulse and sparer in texture than the complex, opening statement. Feinberg’s playing was intense and seemed to take him to the edge of exhaustion.

The Third Sonata rushes by with a density that can be hard to follow. The Fourth Sonata is even richer with ideas, but it is easier to hear them in the moment and fit them into their large-scale form. The Fourth is a great composition with superior craft, laid out in four movements, alternately declaratory and ruminative. Perhaps it’s Wuorinen’s Hammerklavier – there is literally more space in the music; the intervals tend to be wider and the chords thinner than the other two piano pieces. There are short phrases and rhythmic patterns with which Wuorinen builds the first movement, which ends with a short, descending figure that sounds like a question mark.

The middle movements, a scherzo and a slow one, sound like the composer thinking of the nineteenth century via Berg. There are ghostly, expressionistic fragments of a waltz that appear and quickly vanish in the scherzo, flickering channels of the past, and the slow movement is almost mystical.

McDermott’s playing was beautiful and lyrical. The finale is an intellectual summation of the music that came before, and finishes with the same descending figure that, in the new context, sounds like a period. If the question was about the meaning of the past, the answer is that Wuorinen has transformed it into the present.

Music at the Morgan continues with “Caroling at the Morgan,” 6:30 p.m. December 13. themorgan.org