Penderecki’s past is prologue for a night of chamber music at Symphony Space

Inevitably, there was the Johnny Greenwood question.

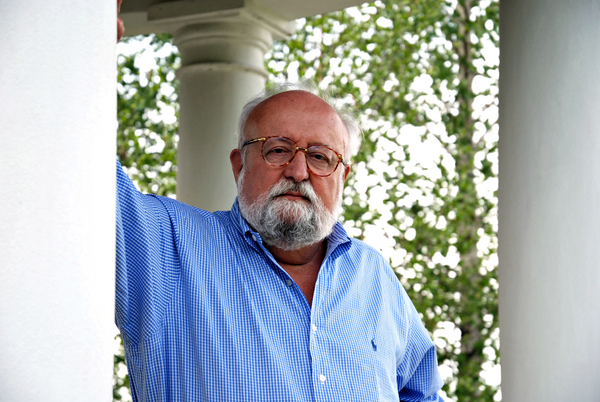

Symphony Space produced a concert honoring Krzysztof Penderecki Friday night, which was also broadcast live via WQXR’s Q2 internet radio station, with singer Helga Davis hosting. She asked about the composer’s recent collaboration with the Radiohead guitarist.

Penderecki responded politely, talking about how Greenwood approached him after discovering the composer’s 1960 masterpiece, Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima. What Davis hinted at, but never asked in her rambling commentary and questions, was how the composer of that famous avant-garde work evolved into the same composer who produced the deeply rooted chamber music that was heard in the hall.

Penderecki turns 80 next month, so this was an early birthday party. And he is clearly the same composer who wrote the early works and Cadenza for solo viola, the Clarinet Quartet, the Sextet, the recent String Quartet No. 3 “Leaves from an Unwritten Diary” and the Capriccio per Siegfried Palm, for solo cello. That last is almost fifty years old now, and was the only music that showed his early aesthetic.

Capriccio is a concentrated survey of extended cello techniques that takes the form of a virtuosic and emotionally expressive solo. There is a heavy percussive element, not only the musician’s hands against the body of the instrument, but the fingers hammering pitches against the fingerboard, the opposite of pizzicato. Penderecki uses that technique, and others like it to serve a musical idea—like playing the strings just above the bridge and from behind them, which produces an uncanny sounding double-stop.

In the case of the Capriccio, that idea is dramatic and relatively tonal, with some perfect cadences and a climactic central pitch. The young cellist Jay Campbell gave what the composer described afterwards as “I think the greatest performance of this piece.” It well may have been. The notation holds no challenges to Campbell’s technique and, notably, Campbell understood why he was going from note to note, technique to technique. The music made sense to him, and he made it sound almost easy.

The Capriccio served as a logical bridge from the avant-garde focus on a radically simple idea to Penderecki’s ongoing style. His language is fairly described as Romantic, but his structural sense is still the same one that produced the cello piece and Threnody. He’s the same composer, but here he whispers instead of screaming. The Cadenza has a lilting tonal quality set to a rhythm that keeps obsessively circling back on itself, and a simple theme that is the context for the soloistic figurations. It was beautifully played by violist Matthew Lipman.

The String Quartet, played by the Penderecki Quartet, was written in 2008. It’s an admirable composition that reveals itself slowly, doling out scattered information that eventual coheres into a magnificent whole. It goes through four distinct stylistic ideas in the first few pages, seeming to play with discontinuity. But then earlier elements return, like a march rhythm that consistently starts then abruptly stops. There’s a lyrical center, with a melody that comes out of folk music, and it ends with something like puzzled lamentation. The composer described some of the music to the audience as coming out of his memories of his father playing the violin many years ago.

The musicians — Jeremy Bell and Jerzy Kaplanek, violins, Christine Vlajk, viola and Katie Schlaikjer, cello — played the piece with discipline and intelligence. They stuck with the elusive form without hinting at the future, the key conception in the music. Vlajk was off in her intonation the first time she played an important theme, but played with strength and clarity at its reprise in this impressive performance of a structurally challenging work.

The Sextet and Clarinet Quartet are major works. Penderecki said both were “conversations between friends, where not everything needs to be said.” In the Sextet, those friends are arguing, and there is general disagreement over where the music should go. Individual voices, like the piano or clarinet, speak up, then are joined by allies and opposed by other factions. The horn regularly interrupts at key moments, putting a stop to the musical motion. There are echoes of older music, pieces that the composer is responding to, like the Grosse Fugue and chamber music from Debussy.

The Sextet is divided into two sections, the first active, the second spacious – the horn moves to a stand some distance from the rest of the ensemble – and there’s an impression of a change from aggression to reflection and regret. The voices finally come together, committed to comity, or at least intent on putting an end to the argument. Ensemble Pi played the music with expressive intensity, first agitated and then weary and unsettled.

While the language of the Clarinet Quartet is the same, the form and means are totally different. Here the model is Bartok, especially his string quartets, with the instruments responding to and supporting each other. It was played by four young musicians from Yale – clarinetist Eric Anderson, violinist Nathan Lesser, violist Colin Brookes and cellist Alan Ohkubo. The playing was stiff at first, handling the notes capably but superficially. Then, in the final “Abschied: Larghetto” movement, the most significant part of the piece, they slid like swimmers under the surface of the music and captured the feeling of dusky mystery in this powerfully expressive work. There was no need for more questions.

Symphony Space will present a centennial tribute to Witold Lutoslawksi December 13. symphonyspace.org