Fischer, Budapest Festival Orchestra bring fresh thinking to familiar music

Ivan Fischer conducted the Budapest Festival Orchestra Sunday at David Geffen Hall. File photo: Hiroyuki Ito

Innovation, disruption. Words can get tossed about so promiscuously they lose all meaning and relevance. These days, especially, the packaging or the formatting — an app, the web — has become more important than the thing itself. It’s still just a taxi ride. It’s still a person writing words. But everyone must innovate, say the forces of the market and society. And so the classical music world has been trying to innovate, for most of this century, with barely a shred of aesthetic or economic success to show for it.

Meanwhile, some musicians simply try and think about the music they play, how to refresh it, and how to make the nth performance of a piece worthwhile, even questioning the how and why of concertizing.

One of the foremost of these is conductor Iván Fischer and, by extension, the Budapest Festival Orchestra. Like others in his field, Fischer wears a tuxedo, wields a baton and programs music by dead people, as he did for Sunday’s Lincoln Center Great Performers series concert at David Geffen Hall. Despite the old-fashioned guise, however, Fischer is an authentic innovator.

The frame he and the musicians placed around Sunday’s matinee — Bach’s Orchestra Suite No. 2 in B minor and Rachmaninoff’s “Vocalise” as an encore — was something new. One may be struck by the conjunction of newness and those almost prosaically standard pieces, and indeed the innovation involved was subtle — this is classical music, after all, with close to 1,000 years of accumulated knowledge held together by the symbolic vocabulary of twelve notes. Big changes come via small decisions.

The first was to perform the Orchestral Suite No. 2 with minimal forces behind flute soloist Gabriella Pivon. Fischer cued entrances to each movement, then handled the organ duties himself, joined by a string quartet, bass, and harpsichord.

The BFO is not a period ensemble playing early instruments, but this arrangement was heavily influenced by that movement’s ideas (themselves innovative in the pure sense of taking apart staid practices). Pivon handled a wood flute, the strings played senza vibrato, the dotted rhythms had an extra sharpness, and phrases had a determined, curving slope that is not heard in prevalent orchestral playing.

This was new in the context of this ensemble, but of a piece with ideas like Fischer’s radical rethinking of how Don Giovanni can be staged. All the nonessentials are cut in a return to just the music. It’s not austere, because the music itself is so rich. On Sunday the ensemble played the dance movements with the right bounce, and despite — or maybe because of — some wayward string intonation, the sound had a lovely color.

The first half finished with Beethoven’s Piano Concerto No. 3 and Dénes Várjon as soloist. This was the pianist’s show, though one was also left thinking that every Beethoven soloist would like this orchestra behind them — their mahogany-and-walnut sound seems ideal for the composer.

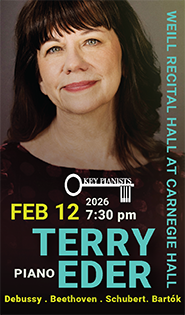

Várjon seemed like an ideal soloist. His percussive attack and articulation brought out the last full measure of Beethoven. The composer’s intellectual force and personal drive encourage performative public statements, even polemics, in the playing. By refining that impulse — expressing Beethoven’s lyricism through logic, not legato — Várjon made the somber dignity and earthy, physical energy in the music vivid. Everything Várjon decided, including playing Beethoven’s cadenzas, sounded right in a way that foreclosed any thought of a superior alternative. Less cogent was his encore, Bartók’s Three Hungarian Folk Songs, which were well played but sounded jarringly out of place.

There was nothing new or even fresh in the programmed second half. The orchestra played Rachaminoff’s Symphony No. 2, a piece that seems impervious to new thinking. This was an impressive performance, refined and with an unflagging energy that tried to squeeze everything possible out of the composition. There’s only so much that can be done with it, though. The symphony has Rachmaninoff’s typical lyricism, and his trademark resetting of harmonies from minor to major. The form is straightforward, but there’s not enough structural thinking to keep the piece meaningful for all of the hour or so it takes. (This was the uncut version.)

To the orchestra’s credit, the performance itself was never dull, and when the music combined expression with proper structural support, the experience was affecting. But Rachmaninoff left so much out — sonata-form themes return, unaltered; the orchestration is monochrome and underdone — that no one could fill in. A case in point was clarinetist Ákos Ács playing the long solo in the Adagio movement. His bright, sweet sound was wonderful, but despite what one is told, Rachmaninoff’s melody is uninventive and gradually becomes a bore.

But then there was the encore, something so old it was radical. As the orchestra has done in the past, they sang the “Vocalise,” with the female musicians standing while the men played accompaniment on instruments. That this was in no way a polished performance was irrelevant — pulling up the roots of music as a social activity was as charming as can be, and it connected with the audience in a way that no concert ceremony, including the ceremony of programming, ever could.

Concerto Köln plays the Four Seasons and other works by Vivaldi 7:30 p.m. January 25 at Lincoln Center. LCGreatPerformers.org