“Quixote” rallies and “Kaddish” bristles at Philharmonic’s Bernstein Festival

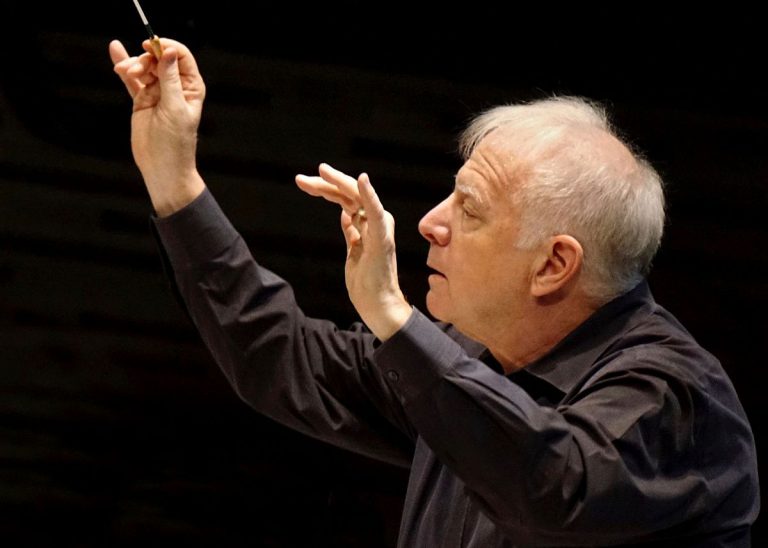

Leonard Slatkin conducted the New York Philharmonic in music of Strauss and Bernstein Thursday night at David Geffen Hall.

The story improves with each retelling: November 14, 1943, the New York Philharmonic’s music director, Bruno Walter, fell ill shortly before the orchestra was going to play a concert, to be broadcast on the radio, in Carnegie Hall. The new, young, associate music director, Leonard Bernstein, filled in.

Without the opportunity for a rehearsal (without even a tuxedo), Bernstein led the program of Schumann, Miklós Rósza, Strauss, and Wagner. He dazzled listeners in the hall and in their homes — Serge Koussevitzky sent a congratulatory telegram — and was immediately on his way to becoming one of the great musicians of the 20th century.

He had an enormous break, of course, but also the enormous talent to take advantage. After Charles Ives, Bernstein is the most important figure in American classical music, and his long and brilliant association with the Philharmonic is being celebrated this month with “Bernstein’s Philharmonic: A Centennial Festival” (he was born August 25, 1918).

With Leonard Slatkin as guest conductor, the orchestra opened the latest installment in the series Thursday night with an odd program that reached for nostalgia and made a stubborn, and seemingly impossible, argument. Two pieces, two different aspects of Bernstein’s career: Strauss’ Don Quixote and Bernstein’s “Kaddish” Symphony (No. 3).

One half playful, the other somber, both were sides of the man. Don Quixote was part of the program back in 1943, and that performance is generally regarded as one of the great interpretations of the score. That was the ode to nostalgia — the untenable notion that one honors someone by recreating what they did.

Except for going through the motions, one can’t. The nervous tension of that debut and the musical energy it produced were unique to that moment. And at the opposite extreme, Thursday night’s performance was low–energy for a good chunk of the piece.

Slatkin used his baton with precision, and the orchestra was relaxed, to the point of sounding casual, good-humored but also disinterested. Strauss’ peripatetic gestures came off as wayward and confused, the Introduction wandering like an amiable drunkard.

Principal cellist Carter Brey played the Don Quixote solo part, with principal violist Cynthia Phelps as Sancho Panza, playing from her first chair position. She stood out in tone and execution from the rest of her section. Brey was excellent, for a long time the only orchestral voice moving forward with a clear sense of direction and purpose. The tenderness he brought out, and his cantabile phrasing, were touching and satisfying.

The performance did gradually come together as the piece went along. At the lush melody that comes after Panza’s appearance in Variation 3, everything came into focus and the orchestra’s energy picked up. From there to the end, the music was played well, but going by the number of patrons nodding off in the orchestra section, not every drifting mind was brought back to attention.

The playing in Symphony No. 3, in the second half, was exactly what one should expect every night from this orchestra: muscular, springy, precise. Augmented by the Concert Chorale of New York, the Brooklyn Youth Chorus, soprano Tamara Wilson (in her Philharmonic debut) and speaker Jeremy Irons, they made a great sound.

The drawback to the second half was the piece itself — Bernstein was an inconsistent composer, even within the course of a single work, and the “Kaddish” symphony is a challenge to pull off. It can be played, but the arguments it makes are so connected to Bernstein’s ego that it may not succeed.

Thursday night, it did not succeed. The commitment from the musicians was there, and Wilson was as affecting as always, her voice like a shining lance cutting through the music and piercing the audience.

Irons was a problem, though it wasn’t his fault. This was a case of bad casting, his cultured, plummy British accent all wrong in a part that demands New York earthiness.

This is mood music based on the traditional Jewish mourning prayer, pressed to a neurotic degree by Bernstein’s libretto, which is an argument with God. The symphony relies on the speaker to make this meaningful and sincere without drama, and Irons’ patrician, observant manner couldn’t capture the right mood — he sounded like a fantasist holding an imaginary conversation out loud in public. Bernstein’s own ethos as a musician was to go full speed ahead as deep into expression as possible, and that seems the only way to perform this part.

The music itself is often overwrought, but also full of eerie colors and plenty of dynamism. The choral settings of the prayer could stand alone as an affecting piece. These were the strongest parts of the performance, both for the orchestra’s playing and the full-bodied singing of the choruses.