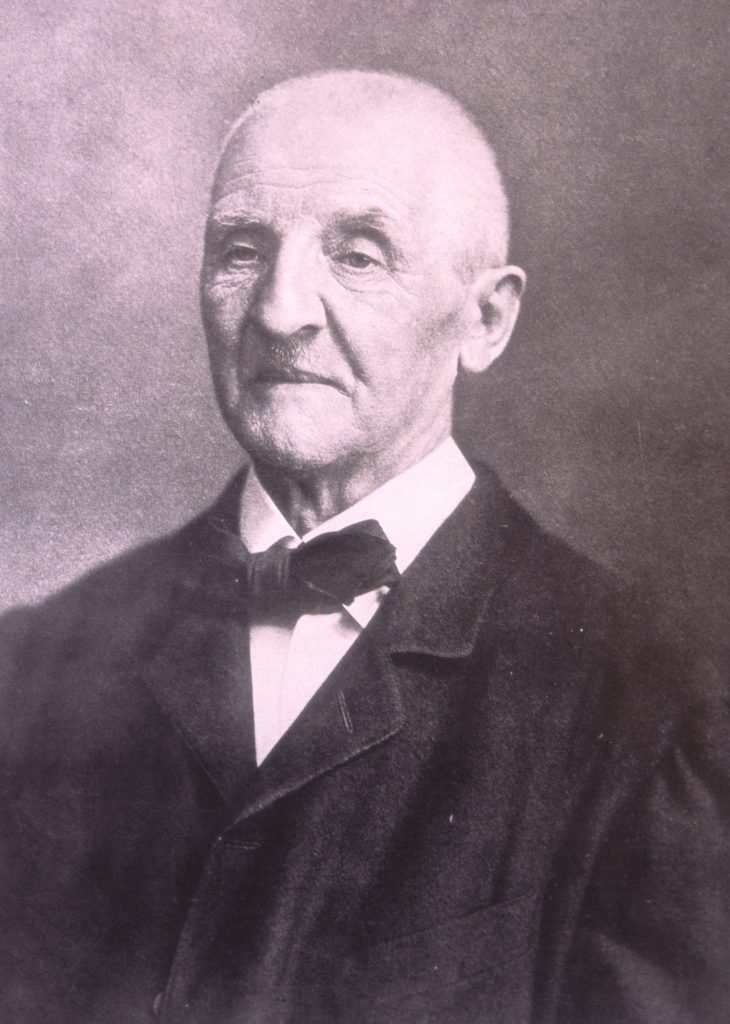

Barenboim, Staatskapelle Berlin reach the summit in Bruckner’s Eighth

Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 8 was performed by Daniel Barenboim and the Staatskapelle Berlin Saturday night at Carnegie Hall.

The cycle of Bruckner’s nine numbered symphonies resembles in shape one of his symphonic movements: a series of peaks, each loftier than the last. Many would say the Symphony No. 8 is the most exalted of them all.

The intrepid alpinists of the Staatskapelle Berlin and their music director Daniel Barenboim reached that summit Saturday night at Carnegie Hall, showing no signs of fatigue in the tenth day of their eleven-day traversal of these massive works.

And this despite the fact that (to change metaphors) the Eighth is the Heartbreak Hill of the Bruckner marathon, the longest work and the severest test of concentration in the entire course.

Gone are the familiar comforts of traditional form and buoyant rhythm, vestiges of which linger in the earlier symphonies. Interpreters of the Eighth must contend with subjectivity and doubt on every side, in a twilight struggle toward faith that is not resolved until the work’s very last pages.

Barenboim and his players realized the Eighth’s wonders of scoring and fluctuating emotion with the same rich sound palette and unflagging attention to detail they have been exhibiting throughout these historic concerts.

Bruckner’s Eighth begins and ends much like Beethoven’s Ninth: A menacing theme emerges from shimmering chaos at the opening, only to return an hour and a quarter later, in the work’s closing bars, as a major-key affirmation for the whole orchestra in unison.

On Saturday, the symphony seemed to lie around in bits and pieces as Barenboim began it, a bit of soft tremolo here, a snatch of theme there, everything disorganized. That this was an interpretive choice and not a sign of inattention soon became apparent, as the wonders of Bruckner’s sonic imagination began to reveal themselves.

Bruckner’s famous fortissimo climaxes came in all sizes and colors. Some seemed to well up from the depths, others to arrive on a cushion of lush brass, others to strike with hammering force.

Just as suddenly, a sweet-toned solo flute or oboe might be left hanging, alone and vulnerable, in a pianissimo haze of string tremolos. The composer’s vision of the soul’s journey through tribulations could hardly have been more present in this performance. The first movement’s last, most harrowing climax literally lifted players from their seats as they strove for the ultimate in tragic expression.

This work’s Scherzo is no light interlude, but on Saturday its felicities of scoring were fully on view, beginning with a superb additive crescendo that brought the orchestra’s sections in one by one, swelling the music from pianissimo to fortissimo. Strings sounded rich with double-bass sonority one moment and electric with urgent tremolo the next. Woodwinds had their moment in the spotlight, curling luxuriantly over a soft timpani beat.

The Adagio showed, among other things, that this orchestra had as many shades of pianissimo as it did of fortissimo. Subtle surges and hesitations held the listener’s attention in page after page of the softest dynamic, and the players’ inflections could hardly have been more unified if Barenboim had held a volume knob instead of a baton.

The vast movement, rich in incident and featuring (of course) a progressive series of brassy climaxes, was held together by Barenboim’s steady, well-judged tempo, unhurried but also, as the score instructed, nicht schleppend, not dragging. A certain tug of yearning, of reaching for something, held even the softest passages taut.

The orchestra’s eight horns glowed in the movement’s final benediction. Then, in the evening’s most breathtaking moment, they did the seemingly impossible for this instrument, maintaining their rich, clear tone in a diminuendo to the faintest pianissimo, then silence.

Barenboim allowed that charmed silence to linger for a long time before he tackled the finale, a complex piece with the burden of resolving the many conflicts and doubts that preceded it. From the barking brass and pulsing strings of the opening to the lush string theme that followed and further incidents large and small, the orchestra played with its by-now-familiar cohesion and vivid characterization, while Barenboim saw to the transitions that kept this episodic music moving forward.

With each of the orchestra’s sections sounding transparent yet well-matched, the conductor was able to explore the waves and shadings within the movement’s long, suspenseful crescendos and shape the particular sonority of each climax as it arrived. The composer’s unconventional yet compelling symphonic argument gradually built to its brilliant, ecstatic resolution in C major, the high point not only of this symphony but of the entire cycle.

There is still much to look forward to in Bruckner’s incomplete, testamentary Ninth Symphony, especially considering the record of exceptional performances so far in this series. But the Eighth, standing alone on its own evening, wrestling so openly and courageously with the great issues of Bruckner’s art, will occupy a special place in the memory.

The Bruckner symphony cycle concludes with Mozart’s Piano Concerto in A major, K. 488, and Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9, 2 p.m. Sunday at Carnegie Hall. carnegiehall.org; 212-247-7800.

Posted Jan 30, 2017 at 10:30 am by Craig Zeichner

Great review. Some folks commented on Barenboim’s tempo in the slow movement, thinking it too slow. I thought perfectly well-judged and arguably, along with the 9th’s finale, the high point of the cycle. Also thought Barenboim’s performance of the A Major concerto his best of the cycle. What a life-affirming two weeks it has been.