Bach and Lachenmann converge and contrast at Miller Theatre

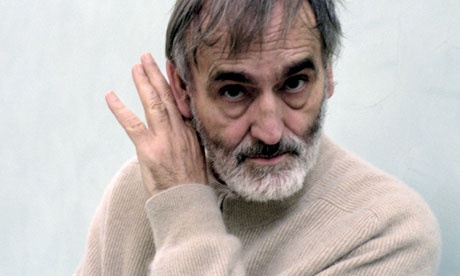

Helmut Lachenmann’s music was performed in the “Bach, Revisited” series Thursday night at the Miller Theatre. Photo: Marion Kalter / Lebrecht Music

The “Bach, Revisited” series at Miller Theatre collapses the past into the present, and no program to date has had as wide a distance to cover as the one Thursday night that paired Bach with avant-garde composer Helmut Lachenmann, performed by members of Ensemble Signal.

Previous concerts have partnered Bach with the likes of Kaija Saariaho, Joan Tower, and Michael Gordon. All those composers use pitch, as Bach did, but Lachenmann is different. Lachenmann is known for his use of non-tonal sounds and timbres.

But he does not ignore pitch completely, as shown by his Third Part for J.S. Bach’s two-part invention in D minor. As the title indicates, Lachenmann adds a third part to Bach’s work (flutist Kelli Kathman joining violinist Ari Streisfeld and cellist Lauren Radnofsky). The contemporary addition (from 1985) is so seamless that it says little musically, other than that Lachenmann knows how to handle baroque counterpoint.

His other pieces on the program—Toccatina for solo violin, Pression for solo cello, and TemA for voice, flute and cell—use his vocabulary of sounds. The Allemande and Sarabande from the solo Cello Suite No. 5, and the Chaconne for solo violin, represented Bach’s tonal language, and each set the context by opening their respective halves.

Lachenmann is firmly in the avant-garde, but the point of the avant-garde is that, for example, if the idea of A can change through the centuries, why can’t the idea of pitch, and sound? His sounds are what a composer can do if he gets tired of all the As, Bs, Cs, and Ds.

And the sounds themselves are full of pitches, from the barely audible little quasars Streisfeld made by tapping the metal point of his bow handle against the strings in Toccatina, to the complex blend of pitches Radnofsky produced when she scraped her bow across her cello’s bridge, to the dramatic, breathy sounds mezzo-soprano Rachel Calloway, Kathman, and Radnofsky made in TemA.

In a way, Bach had it easy. While counterpoint and fugue are strict and demanding, making counterpoint with abstract sounds in exact tempo and rhythm, as inTemA, is daunting—there are no guidelines, and one has to manage one’s own rules.

The musicians played Lachenmann with dedication to his forms and structures, his subtle but clear sections, transitions and cadences. TemA was especially well done, the musicians turning the long stretches of silence into gripping chunks of measured time, and Calloway making a sense of drama feel innate to the composition.

Rhythm is where the two composers are closest. Lachenmann structures time through carefully placed events, and the past can peek through: Toccatina has a march rhythm chopped out by the bow against the strings.

Rhythm is essential in Bach. If the melodies and harmonies are about the beauty of resolution and the glorification of God, the rhythms are about the body, and how it dances. That was the weak spot in Radnofksy’s playing of the Allemande—she kept switching back and forth from sharp edged rhythms to a more legato, lyrical manner. The Sarabande, though, was fully coherent and melancholy. She seemed far more comfortable playing Lachenmann’s music, where she was in command.

Streisfeld was scintillating playing the Chaconne. Initially, he played with rigor, then gradually seemed to give up control of the piece. The key moment was his rapturous playing of the rapid, arpeggiated chords that come about halfway through the piece. From there, the music was in charge and playing through him.

“Bach, Revisited” continues with the music of Sofia Gubaidulina, 8 p.m. May 8. millertheatre.com