Rouse’s massive Requiem proves inspiring and impenetrable

Christopher Rouse’s “Requiem” received its New York premiere by Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic Monday night at Carnegie Hall.

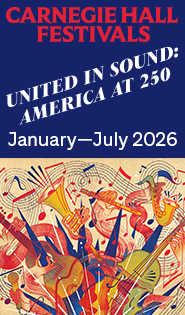

Spring for Music, the annual festival that brings talented orchestras from across North American to Carnegie Hall to play imaginative programs at affordable prices, is in its fourth and, sadly, final year. The series has brought groups from smaller cities to well-deserved exposure in front of enthusiastic crowds of hometown supporters and New Yorkers alike.

The visiting orchestra for the opener Monday night came from just up Broadway, however: the New York Philharmonic, conducted by Alan Gilbert, followed by fans waving orange towels, as if the Giants were about to win the pennant. Joined by the Westminster Symphonic Choir, girls of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus and solo bass-baritone Jacques Imbrailo, the Philharmonic played the energetic local premiere of composer-in-residence Christopher Rouse’s Requiem. The piece, commissioned by Soli Deo Gloria and written in 2002, is fascinating, massive, ungainly, often moving, sometimes unhinged: if not a completely successful composition, at least an impressive showcase for musicians and composer’s craft alike.

Rouse modeled his piece after Berlioz’s own great Requiem—music the composer admires— and wrote in in part to honor the bicentennial of Berlioz’s birth. Rouse used the same version of the Latin text that Berlioz did, and added his personal stamp by interpolating poetry from Seamus Heaney, Siegfried Sassoon, Michelangelo, Ben Johnson, and John Milton, along with English and German hymn lyrics and their accompanying music. Until the very end, the singing duties are divided based on the text: the chorus sings the Latin and the soloist sings the poems.

Despite the mishmash of sources, the string of words stays true to a central conception. This is not a requiem mass meant to succor the living, but one that often appears to be sung by the dead themselves, from a place far removed from Paradise. This makes it close in spirit to Berlioz’s piece, and it conveys something of the terrors that Verdi limned in his own Requiem. Musically, though, the central idea appears to give Rouse an anchor that he feels will hold the whole thing together, no matter what he does and where he goes.

Things don’t quite work out that way. Rouse’s version began with Imbrailo singing a solo to Heaney’s “Mid-Term Break,” a poem about death. Imbrailo was impressive as the title character in the English National Opera’s visiting production of Billy Budd at the beginning of this year, and hearing him merely singing confirms that he is an excellent musician. His voice is rich, with both throaty and nasal tones, and he has a sweet, expressive sense of phrasing. Rouse’s setting is fine, with a sure sense of meter and a lyricism that matches words to music in a way that sounds intuitively right. It’s a great song.

All the solo passages in the piece are great, the choruses less so. Where the poems bring out the composer’s subtlety and imagination, the Latin text becomes an anvil, the chorus and orchestra a hammer. This is not apparent at first: the initial choral entry is a cappella, the men and women singing the “Requiem aeternam” in chromatic lines that slide eerily past each other. But the haunting effect doesn’t last.

As soon as the third section starts, the “Dies irae,” the pounding begins, and it is a massive pounding. Rouse is something of a maximalist as a composer, and with over a hundred musicians, he maximizes volume and density. This is physically exciting at first, but as time passes, and as loud section follows loud section, the ear becomes inured to the quality and the structure starts to feel scattershot, gestural. The orchestration is thick enough that it’s not really possible to hear everything that is happening, other than an overall sensation of force.

The piece is a workout for the conductor, and Gilbert was constantly cueing, managing changing meters, keeping the beat moving. The musicians had no trouble keeping the music together, and everyone played and sang with commitment, but there didn’t seem sufficient time and space to say a lot expressively amidst all the activity. The eleventh, “Domine,” section has four or five lines going on at any one time, each with a different pulse. While technically impressive, it is expressively diffuse.

Some of the diffusion is effective. Rouse frequently combines one pulse in the chorus with a different one in the orchestra, and that produces an intriguing drifting sensation, like the music was separated from our own physical realm. But the pulses have to flow, and when, in the “Hostias” section, their energy dissipates, the sensation turns leaden.

Still, especially with a singer like Imbrailo, the bitterness of the texts—such as Ben Johnson’s almost unbearable poem on the death of his son—maintains a power all its own, and a welcoming unsentimental view of how to react to death through music. But Rouse doesn’t follow that all the way through to the end. The concluding pages are a benediction of grace, interspersed with the simple pleasures of triadic harmony. The music sounds great, but to ears committed to the path Rouse lays out, the succor is out of character. The greatest strength of his Requiem is that it peers into the abyss, and the abyss peers back.

Spring For Music runs through May 10. The Seattle Symphony performs 7:30 p.m. tonight. springformusic.com.

Posted May 06, 2014 at 12:46 pm by Curtis

What he didn’t mention is that the “Dies irae” is the most frightening thing ever composed! It was a great concert, definitely the best I have attended.