Piston piano works receive their belated and richly served New York premieres

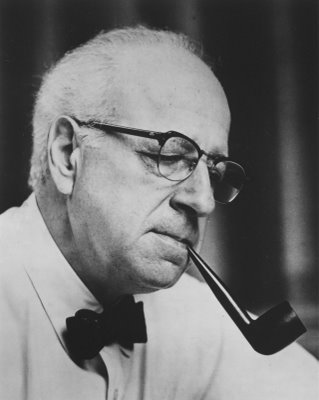

Walter Piston music received two New York premieres Thursday night at SubCulture: the Sonata for Piano and the Concerto for Two Pianos Soli. That the pieces are eighty-eight and fifty years old respectively, and Piston one of the most important American composers of the last century, the belated circumstances were bizarre in the extreme.

The 20th century was the American Century for classical music, with ideas from Ives to Cage to Lou Harrison to Steve Reich and John Adams showing the way out of the style wars and ideological culs-de-sac. Piston was an essential part of this. His music is as fine as that of his peers —Roy Harris, Aaron Copland, William Schuman, David Diamond and Peter Mennin — and his influence far greater. He taught composition at Harvard from 1926 to 1960 and trained, among many others, Elliott Carter, Leonard Bernstein, Conlon Nancarrow, Fred Rzewski and John Harbison. Through his textbooks, he continues to reach countless other musicians.

Why is his music (and that of his peers, save Copland) impossible to find on concert programs? The situation is inexplicable.

Thanks go to the New York International Piano Competition, under the auspices of the Stecher and Horowitz Foundation, for organizing this concert with the young and talented pianists Matthew Graybil and Igor Lovchinsky playing the Sonata, the Concerto and two short pieces, Improvisation and Passacaglia, before closing the concert with Bernstein’s cheeky two-piano arrangement of Copland’s El Salón México.

Graybil has a smooth touch and is a deep thinker, as heard in his playing of Improvisation and Passacaglia, both compositions written in the mid–1940s. These are subtle and exceptionally skillful miniatures that show Piston’s virtues. He was a master of the technical demands of counterpoint and variation, formed a bright and rich harmonic sense by building chords out of fourths and fifths, and filled his music with myriad expressive possibilities. His pieces move quickly but without haste, and he could build a skyscraper out of a single note.

The skyscraper is also an aesthetic of mid-century America, like capturing the Chrysler Building or a Packard Roadster in sound. Piston’s 1926 Sonata, played with both clarity and intensity by Lovchinksy, has the muscular confidence typical of the era and is a great composition.

The form and structure are classical, Beethovenian: a sonata-allegro first movement, a slow middle one and a fast finale. The style, even with hints of Debussy, is original. In the first movement the opening theme is a perpetual motion toccata, the secondary one a series of soft, atmospheric chords, out of which comes a layer of harmony when the principal theme returns.

The slow middle movement directly relates to the secondary theme of the first, and the machine-like fugue that underpins the finale is kin to the toccata music. The variations comes with a rapidity and density belied by the transparency of the writing, even as the fugue moves into a stretto, then smashes into a pounding climax. Lovchinsky provided a tremendously agile performance.

Instead of an intermission, there was a talk from Melvin Stecher and Norman Horowitz of the foundation. In their day, the two men were one of the leading piano duos in classical music, and it was they who commissioned the concerto from Piston. They premiered it in 1964, and introduced this New York premiere (Piston revised the piece in 1967).

It is a feat of real craftsmanship and imagination. Despite constant activity in both pianos — there is a lot of antiphonal writing, solos with accompaniment and polytonal harmonies — every note and line and chord is crystal clear.

This is also a work in classic sonata form with fast-slow-fast movements. With two keyboards, Piston extends the music vertically while keeping his typical horizontal drive. He builds harmonic richness without opacity by frequently modes, rather than stacked chords, and orchestrating across the high and low registers.

The allegro opening movement seems atypically repetitive at first, but soon one realizes that Piston has built a grand structure out of a single scale. The middle slow movement is intellectually and emotionally searching without being sentimental — Piston is always grounded. Graybil and Lovchinsky clearly relished playing this piece, and were sympathetic partners, dynamic and interactive both when leading and accompanying.

The pianists played El Salón México with relaxed ease, but the piece sounded rather pedestrian alongside Piston’s music. This work is a known quantity and eminently enjoyable, but the populist gestures seemed trite in contrast to Piston’s clearly spoken rigor. And in contrast to his teacher’s skill in writing for the keyboard, Bernstein’s 1943 Copland arrangement felt muddy and clumsy. The student still had much to learn from the master.

The New York International Piano Competition series at SubCulture continues 7:30 p.m. March 6 with a recital from Kate Liu. stecherandhorowitz.org

Posted Jan 22, 2014 at 3:35 pm by Merrill Hatlen

Thanks for calling attention to Piston’s music, which deserves a wider audience. Stecher and Horowitz premiered his Concerto for Two Pianos at Dartmouth’s Congregation of the Arts in 1964, where Piston was composer-in-residence (as was Copland in 1967). Unfortunately, the 50th anniversary of the debut of Congregation of the Arts in 1963 went unnoticed last year, as did the 75th anniversary of Piston’s The Incredible Flutist. I’m glad to see 2014 start off on a better note, helping to celebrate the 120th anniversary of Piston’s birth (1894).