“The Hours” builds a moving, spellbinding drama in Met premiere

The Hours, which began as an award-winning, best-selling novel, and was then made into a popular film, is now an opera. Commissioned from composer Kevin Puts by the Metropolitan Opera and the Philadelphia Orchestra, The Hours had its world premiere Tuesday night at the Met. Explicitly based on both the book and the film, this is not just an extended cultural franchise but a spellbinding score that has its own unique way with exploring and expressing this complex drama.

This production has operatic star power to rival the movie’s cast of Meryl Streep, Nicole Kidman, and Julianne Moore: soprano Renee Fleming as Clarissa Vaughan, soprano Kelli O’Hara as Laura Brown, and mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato as Virginia Woolf. The production is by Phelim McDermott, who has already delivered important stagings of Philip Glass and Mozart operas to the Met, and music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin is conducting. That immense amount of talent, and Puts’s skill as a composer, made for an evening that had great beauty and reached genuine and considerable emotional depths. The Hours does not fulfill all its promises, but the opera’s heights are as grand as anything one will experience at the Met this season.

Following its antecedents, The Hours, with libretto by Greg Pierce, tells the story of its three characters in crisis: Clarissa is preparing a party for her best friend Richard, who is dying of AIDS; fifty years in the past, Laura is depressed and anxious, hiding from her family and herself. Behind them in time is Woolf, working on Mrs. Dalloway and herself breaking down. A direct link between Clarissa and Laura will be revealed, while Laura herself reads Woolf’s novel and Clarissa, whom Richard calls “Mrs. D,” not only shares the first name of Woolf’s character but is caught in a nearly identical plot.

Thematically, the individual dramas parallel each other, though they resolve differently, which makes a musical treatment ideal and enticing. While events in a book or movie usually happen in sequence, music can synchronize different places and times simultaneously and organize narratives in time in a way that can create great power and resonance. And The Hours does this well.

Puts’ score introduces the characters in sequence, Clarissa first and Laura last. First though is the chorus, singing text adapted, in Pierce’s elegant prose libretto, from the famous first line of the novel. The choral writing is one of the best things in the opera; sung with delicate resonance by the Met Chorus, these passages linked each character and their time period.

The full house, notably younger than usual at the Met, applauded Fleming as the chorus parted and revealed her. A frequent collaborator with the composer, it was a pleasure to hear the simple loveliness of her voice and easy projection. The part seemed carefully designed to sit at an almost conversational level, and Fleming’s singing was both rich in tone and clearly articulated.

DiDonato was just as fine, and again her part seemed to sit in the most comfortable range for her. The role called for a grounded, forceful sense of emotional gravity and turmoil, and she delivered the feeling that every word had weight and meaning.

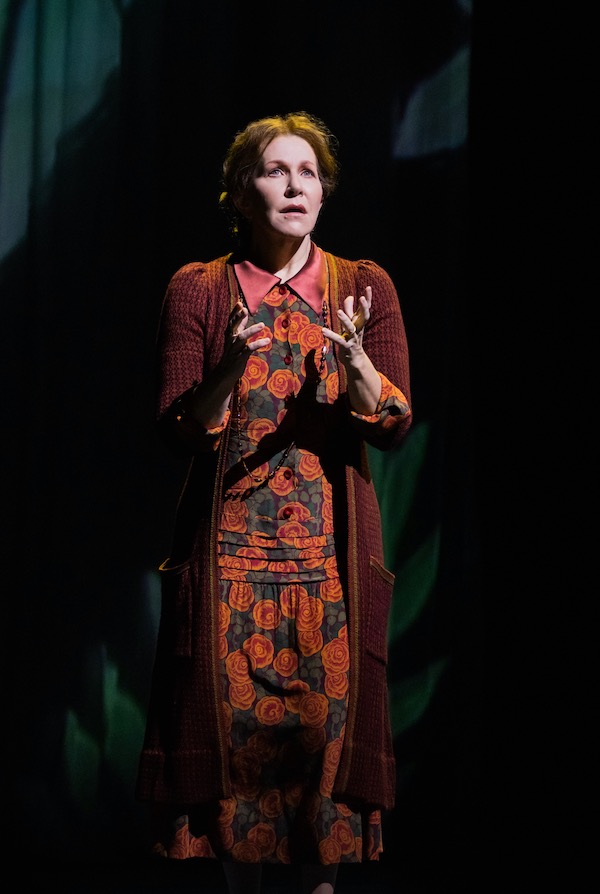

O’Hara is a different kind of singer, her musical theater-style soprano not full in the operatic sense but gliding over the top of the music. Her extensive acting experience gave her a stage presence above and beyond the rest of the cast and out of the ordinary for what one sees at the Met. Her ability to hold attention, even while sitting still, was an intense part of the dramatic experience.

The music for the three had substantial solo passages but nothing in the way of aria-like vocal displays. Puts’ writing is first and last about dramatic narrative. Everything, even dialogue, aspires to song form—setting the words in a line that is shaped and resolved by harmony in a way closer to pop music than the 19th-century operatic tradition. Yet this is in no way simplistic, it instead reaches back to the virtues of Handel and Mozart (without the words being in verse) updated with 20th century classical tonality.

The score is flowing and frequently gorgeous, full of melodic and harmonic resolutions that, like tiles of a mosaic, mark integral bits of the drama and move smoothly to the next element. Puts uses structures and orchestrations familiar from Copland, Barber, and John Adams, and even amusingly quotes from Die Zauberflöte, but nothing is derivative, and it all comes through as his own voice. The accumulated effect of all these details, of one dramatically meaningful piece after another, is often deeply affecting.

The overall feeling is one of poignancy. There are frequent scenes where Clarissa or Virginia are in dialogue with other characters, then slide into solos that reveal their inner turmoil through melodic grace. These are often answered and reinforced by the chorus with chords and cadences that cement the effect of the solo music. Laura’s isolation is reinforced by music that not only sets her apart but alone, building on the relative out-of-place character of O’Hara’s voice and turning it into an intense dramatic advantage.

That is one of the great virtues of the opera—Puts knows how to shape individual vocal scenes into a large-scale narrative, which sets him apart from many of his contemporaries. The first of the two acts is 80 minutes, but doesn’t feel that long and builds to an extraordinary climax. The music hints for a while at bringing together the three characters, across their eras, into some kind of collective individuality, which explodes at the end of the act.

The main characters have many luminous vocal lines, even as the music has a darker yet luscious quality. There are parts of Act I where the music is lighter, and the effect is to bog everything down, especially the obvious, clichéd studio orchestra sound that introduces Laura in 1949 Los Angeles. The main dramatic music is so strong that the passing lighter moments are the only times when the opera seems to drag.

Act II takes a while to get back up to the level of the end of Act I, and for a long opening stretch that alternates between Laura and Virginia, there’s no discernible dramatic thread. This returns when Clarissa herself is back on stage, visiting Richard (the always charismatic bass-baritone Kyle Ketelsen) in the most tragic point of the opera.

There is a big cast of supporting players: mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves was typically excellent as Clarissa’s partner, Sally. Bass-baritone Brandon Cedel was sincere and charming in a role that could easily be a cipher as Laura’s husband Dan. Tenor Sean Panikkar was alternately patient and intense as Leonard Woolf. Boy soprano Kai Edgar sang with confidence and superb phrasing and intonation as Laura’s son Riche.

In the pit, Nézet-Ségiun and the orchestra were at their best, with clear textures and excellent dynamics, a fluid sense of energy and pace without anything overdone. The high quality of the music making left the impression that this was exceptionally well prepared and that all—singers, chorus and orchestra members—were fully involved.

McDermott’s staging keeps things simple, and is at times so minimal as to be nothing more than large slabs of light and dark lighting. As a new work that at the very least needs to speak for itself, the general sense of non-intervention let the music and drama come through. Annie-B Parson’s choreography was at times fussy, and there was too much of it, especially in the Act I climax, but the power of the music plowed over any distraction. This is sure to be a a hit for the Met, and it deserves to be.

The Hours continues through December 15. metopera.org

Posted Nov 24, 2022 at 5:24 am by Emilie de Brigard

That Kelli O’Hara! She is something else! The evening belonged to her and to Joyce Di Donato. Joyce’s magnificent singing commanded attention and Kelli’s acting made me believe. Unforgettable moment: Kelli throwing her husband’s birthday cake in the trash.

Renee Fleming’s character was washed-out by comparison, with singing to match. That gave one something to think about. The woman’s movement has gone backward, perhaps?

Posted Mar 24, 2023 at 8:06 pm by Gene Bivins

I’m a little taken aback by Ms de Brigard going from a comment about Renee Fleming’s “washed-out” performance and “singing to match” to the strange comment “The woman’s movement has gone backward, perhaps?” Just maybe it has more to do with the simple fact that Fleming is 64 years old and came out of operatic retirement to create this role. What it could possibly have to do with the “woman’s movement” is quite beyond me.